Norway rat.

Image credit: Norway Rat, Rattus norvegicus, 2018 collected by Dion Palamountain. Ref: LM002994 Te Papa. Some rights reserved: CC BY 4.0.

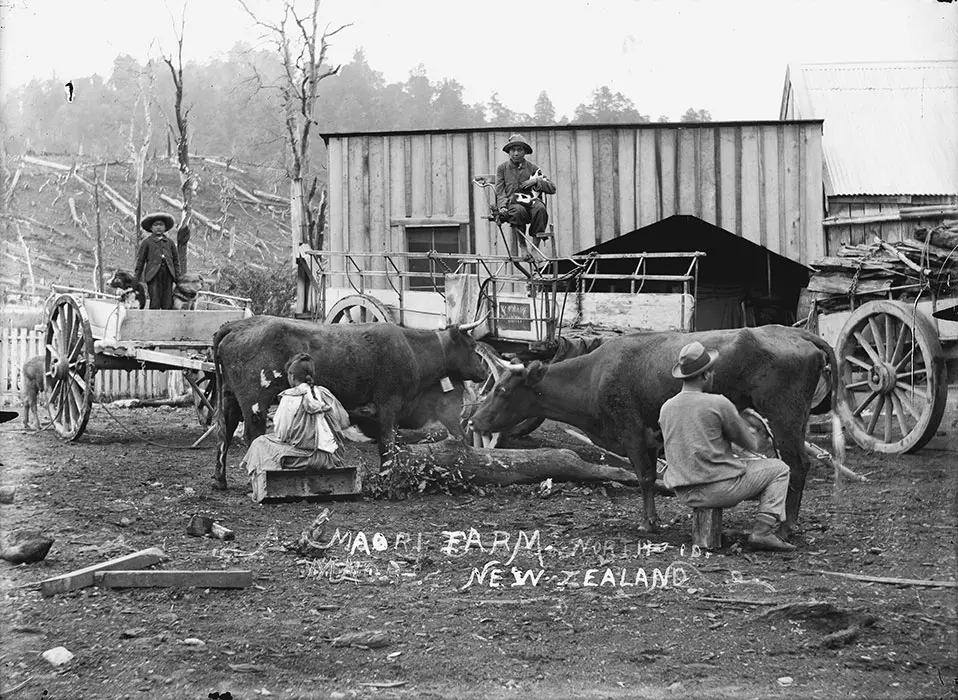

He tini ngā momo kararehe, tupu hou i haere mai me ngā tāngata tauhou ki Aotearoa. Ko ētahi he pōrearea, ko ētahi atu he kai, ko ētahi, he kai, he pōrearea hoki.

I piki mai ngā kiore parauri ki runga i ngā kaipuke o ngā kaihōpara pēnei i a Rūtene Kuki. He tere tonu te horapa, ka kai i ngā hua o ngā manu, ngā pīpī i ngā kōhanga, te aitanga pepeke me ngā mokomoko.

He uri tonu te nuinga o ngā poaka mohoao i te Waipounamu i ēnei rā nā ngā poaka nā Rūtene Cook i hari mai ki konei.

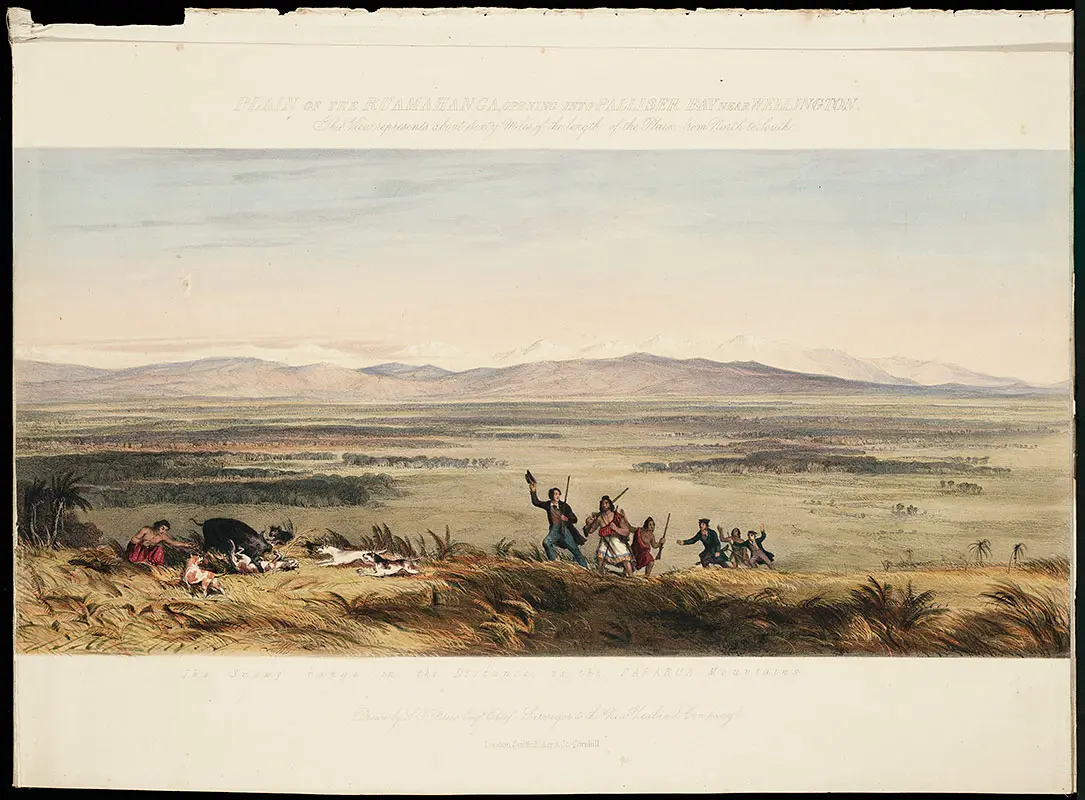

Hunting a wild pig.

Image credit: Plain of the Ruamahanga, Opening Into Palliser Bay Near Wellington. This View Represents About Sixty Miles of the Length of the Plain From North to South, 1843 by Samuel Charles Brees. Ref: PUBL-0011-08-2 Alexander Turnbull Library. Some rights reserved.

New species of animals and plants came with settlers to Aotearoa New Zealand. Some were pests, others were food, and some were both.

Norway rats hitched a ride here on the ships of explorers like Lieutenant Cook. They spread quickly, eating birds' eggs, chicks, insects, and lizards.

Most of the wild pigs roaming the South Island bush today are descended from porkers that Lieutenant Cook brought with him.

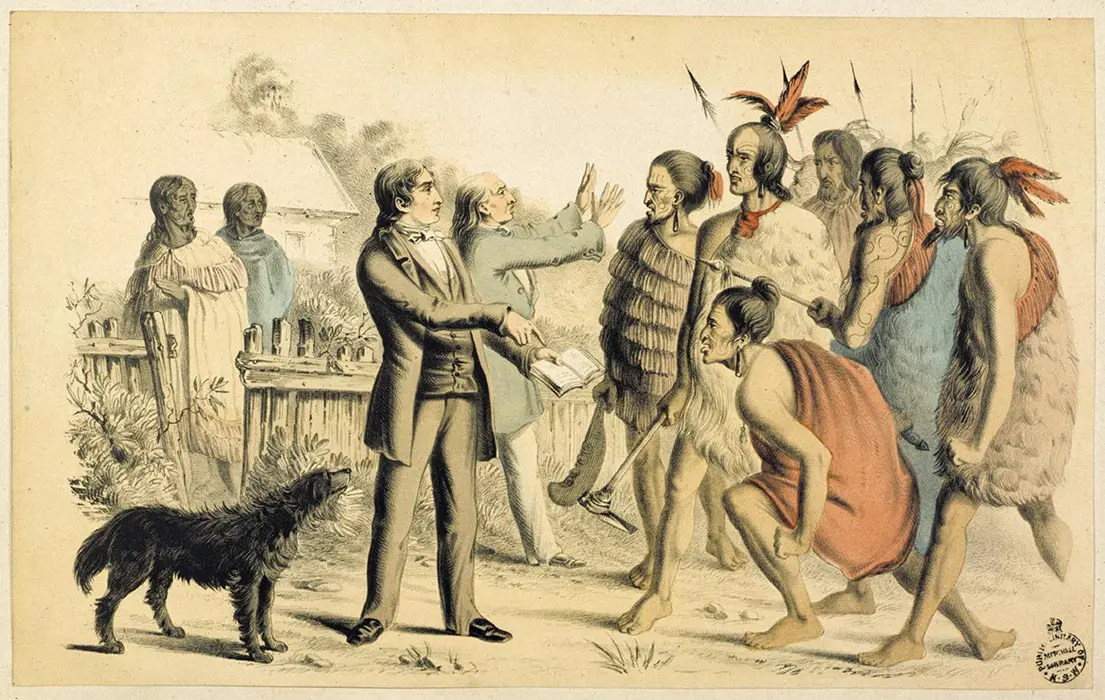

He aha tō hiahia? He aha tāu e hoko mai ai ki a au?

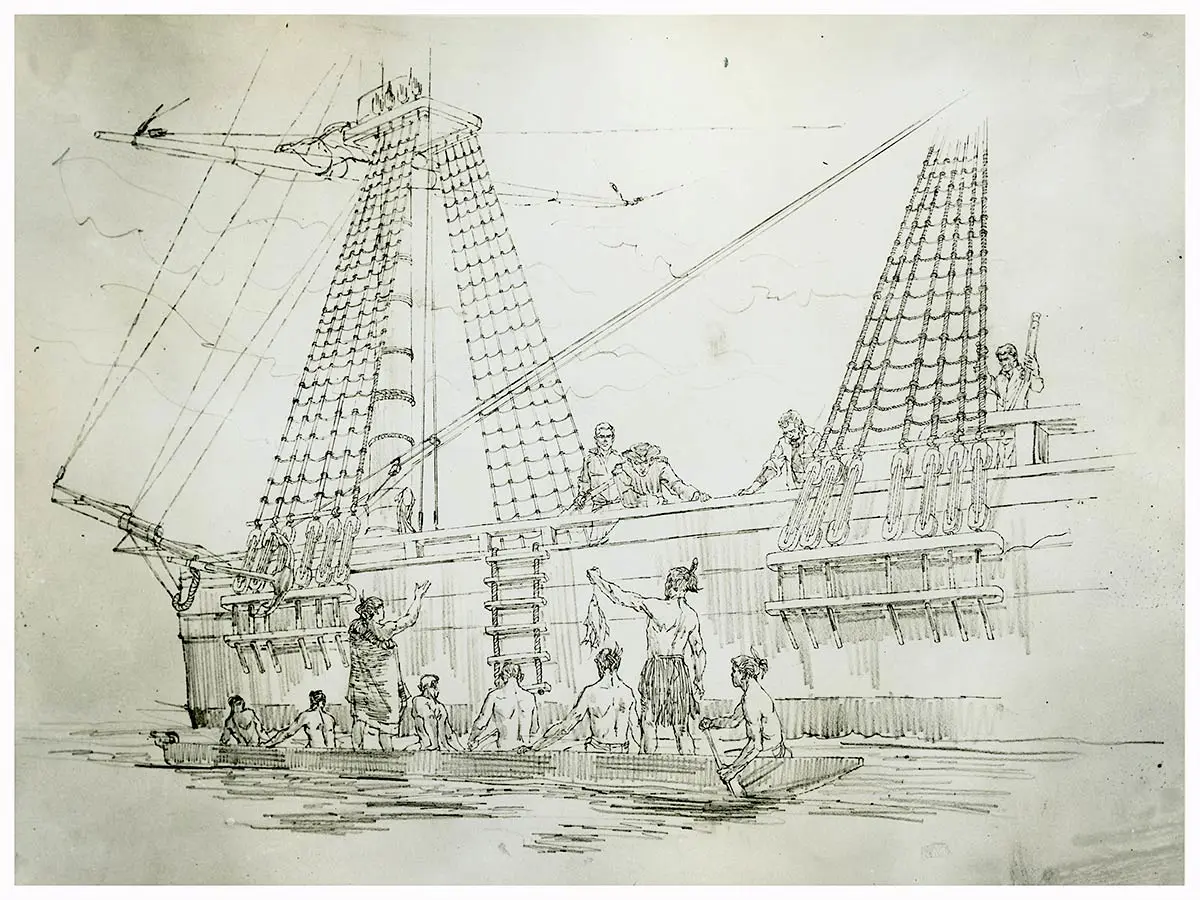

Mai i te tīmatanga i te tauhokohoko te Māori me te Pākehā. Mā te tāpae atu i te kai, i te harakeke, i ētahi atu taonga hoki, ka whiwhi pea koe ki te kākahu, ki te ngutu pārera (pū) me te taputapu, hei utu. I whakakotahi ētahi Māori me ētahi Pākehā kia mahi tahi, he hoko harakeke, hoko rākau hoki ki tāwāhi te mahi.

Ka taunga haere te hunga tauhou ki te ao Māori — e tutuki ai ō hiahia, me mātua mōhio koe ko te mana me te tapu.

What do you need? What can you trade to get it?

From the start, Māori and Europeans were bartering. Offering food, flax, and other taonga (treasures) might get you clothing, muskets, and tools in exchange. Some Māori and Pākehā went into business together, selling flax and timber overseas.

Newcomers adapted to Māori culture — you had to understand concepts like mana (authority) and tapu (sacred) to succeed.

Early trading between Māori and Europeans.

Image credit: Drawing by Vern King of Ship Side Trading With Māori, 1965 by Vern King. Archives New Zealand on Flickr. Some rights reserved: CC BY 2.0. Image sharpened.

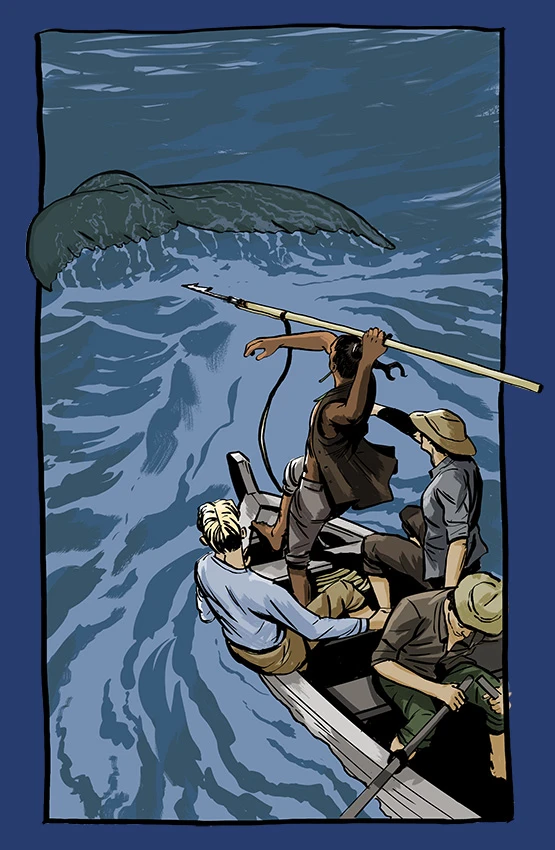

Ko ngā Pākehā tuatahi i haere mai he tangata pakari i tatū mai ki te patu kekeno i Dusky Sound — he mahi tino taratahi, mokemoke hoki.

I ngā tau o muri mai, nā ngā mahi patu tohorā i piri ai te Māori rāua ko te Pākehā. I ngā tau tuatahi mai i 1800, i te tino kaikā a ngāi Māori ki te mahi i ngā kaipuke patu tohorā, mō te moni, me te haere ki tawhiti. He tini ngā kaipatu tohorā noho uta i moe i ngā wāhine o ngā whānau o te takiwā.

Pouring whale oil.

Image credit: Unidentified Maori group pouring whale oil. Photographer unknown. Ref: PAColl-6208-31 Alexander Turnbull Library. Some rights reserved.

The very first Pāhekā settlers were rugged men who came to hunt seals in Dusky Sound — an isolated, lonely task.

Later, the whaling industry brought Māori and Pākehā together. In the early 1800s, Māori were keen to work on whaling ships, for money and adventure. Many shore-based British whalers married into local whānau.

Cutting the blubber off a whale on Mōhaka Beach.

Image credit: Cutting the Blubber off a Whale on Mohaka Beach, ca 1860 by Alfred John Cooper. Ref: A-235-010. Alexander Turnbull Library. Some rights reserved.

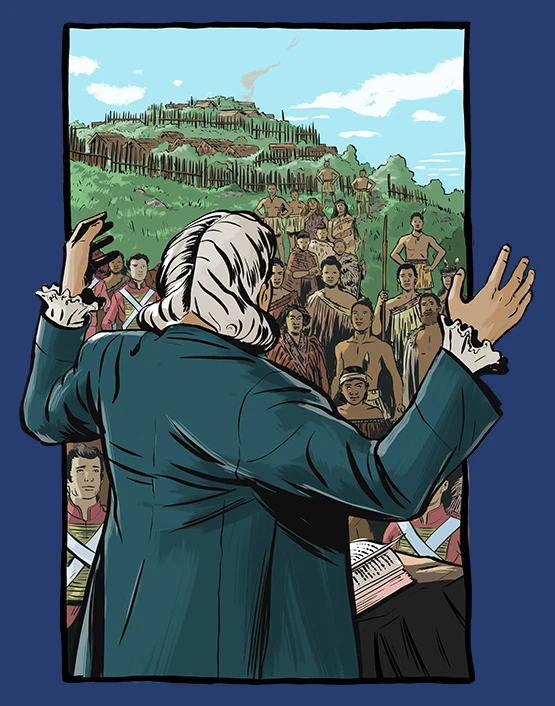

I haere mai ngā mihingare ki te kawe mai i te kupu a te Atua, engari he hononga ā-wairua kē tō te Māori ki te aotūroa: atua (tupuna, atua).

Ka noho ngā mihingare hei takawaenga. I ako te tini ki te kōrero i te reo Māori, ā, ko rātou i whakamārie i ngā raruraru i waenga i te Pākehā me ngā iwi. I te tau 1820, ka tere atu ētahi rangatira e rua nō Pēwhairangi, a Hongi Hika rāua ko Waikato, ki Ingarangi i te taha o te mihingare o Thomas Kendall, ā, ka tūtaki ki a Kīngi Hōri IV.

Māori man holding a Bible.

Image credit: Maori Man Holding a Bible, ca 1840 by Richard Taylor. Ref: E-296-q-076-1 Alexander Turnbull Library. Some rights reserved.

Missionaries came to spread God's word, but Māori already had spiritual connections with the natural world: atua (ancestor, god).

The missionaries acted as go-betweens. Many learned to speak te reo Māori and smoothed things over between Pākehā and iwi (tribes). In 1820, 2 Bay of Islands rangatira, Hongi Hika and Waikato, sailed to England with missionary Thomas Kendall and met King George IV.

A missionary at work.

Image credit: The Power of God's Word, 1856. Artist unknown. Ref: PUBL-0151-2-013 Alexander Turnbull Library. Some rights reserved.

Mai i ērā rā ki ēnei rā he whenua mōmona, rawa nui hoki a Aotearoa New Zealand. I ngā tau mai i 1860, i rere mai te tini ngerongero o te tāngata ki konei ki te keri kōura. Tokoiti noa i kite kōura mā rātou — heoi rā, nā te pōrangi kimi kōura i kōkiri ngā mahi ōhanga kia puāwai.

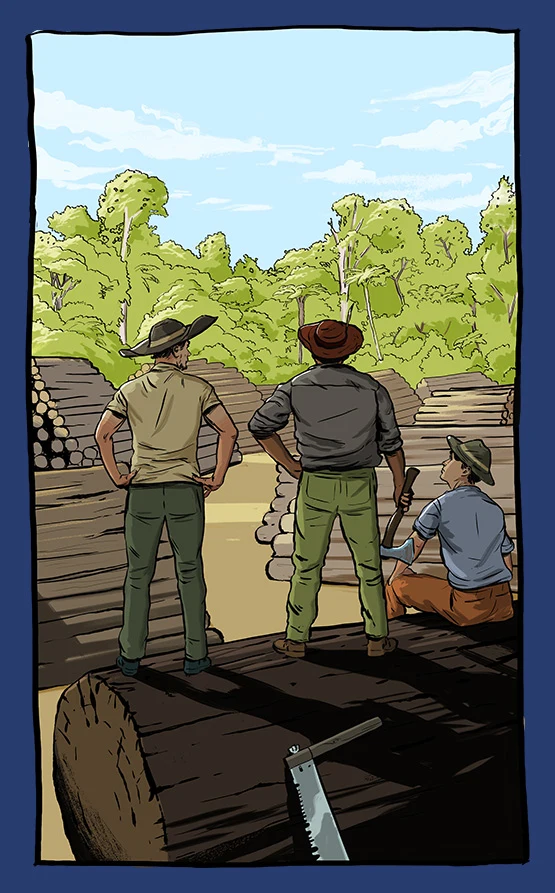

I te hiahia hoki ngā Pākehā ki te tuku taonga whai tikanga pēnei i te rākau, i te harakeke, i te kauri hoki ki tāwāhi.

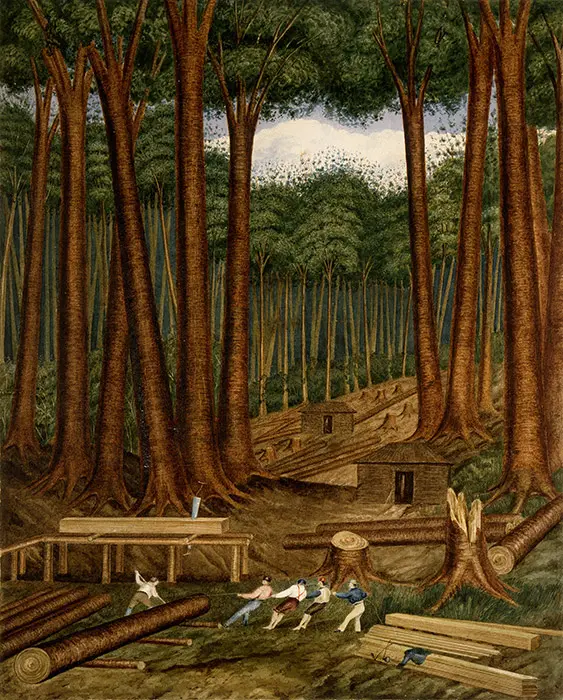

Felling kauri for timber.

Image credit: Kauri Forest, Wairoa River, Kaipara, 1839 by Charles Heaphy. Ref: C-025-014 Alexander Turnbull Library. Some rights reserved.

Making rope from flax.

Image credit: Māori Rope-making, Lantern Slide. Archives New Zealand on Flickr. Some rights reserved: CC BY 2.0. Image sharpened, brightened and desaturated.

Aotearoa New Zealand was, and is, rich in resources. In the 1860s, thousands of people flocked here to dig for gold. Only a lucky few found it — but the gold rush kick-started the economy.

Europeans also wanted to export useful materials such as timber, flax, and kauri gum.

Chinese gold miners.

Image credit: Chinese gold miners. Ref: Album 31_19-1. Toitū Otago Settlers Museum. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Māori kauri gum diggers ready for a day's work.

Image credit: Maori Kauri gum diggers ready for a day's work, 1914 by Arthur Northwood. Ref: 1/1-009777-G Alexander Turnbull Library. Some rights reserved.

He horo tonu te kitenga atu a te tangata whenua, me te hunga nohonoho mai i ngā painga o ngā rawa hou. Ka kitea ēnei rawa i ngā mahi hanga whare, i ngā taputapu me ngā kākahu — i whakamahia i runga i ngā tikanga tūturu mō aua mea, i hurihia rānei kia panoni kē te whakamahi. Te tupuatanga o te waea nama 8.

Tangata whenua and settlers quickly saw the benefits of new materials. These can be seen in housing, tools, and clothes — used as they had been designed or adapted and improved. Number 8 wire genius.

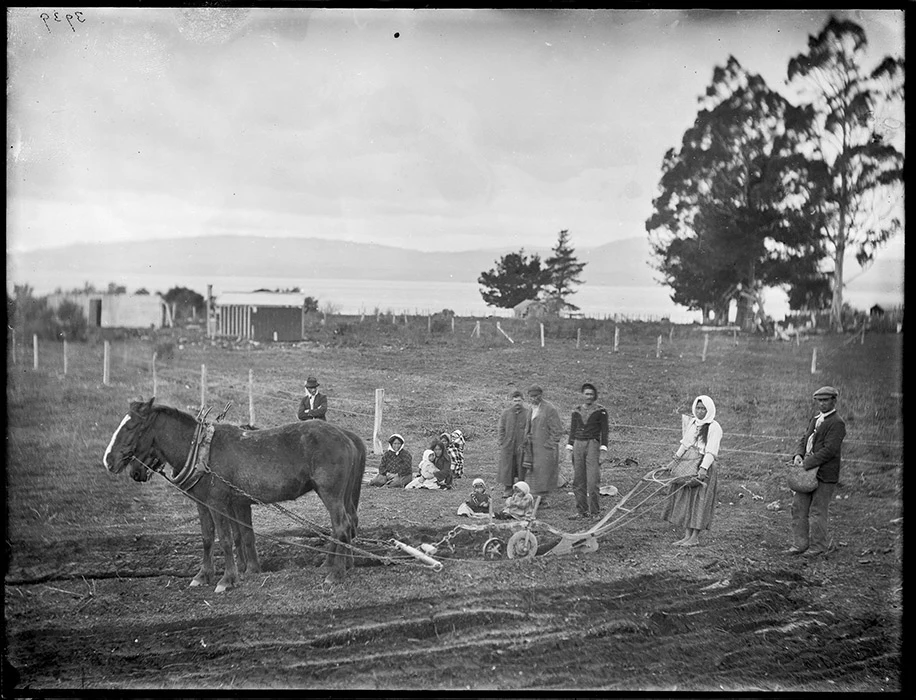

Ploughing a field.

Image credit: Maori woman ploughing a field, ca 1900 by William Henry Thomas Partington. Ref: 1/1-003133. Alexander Turnbull Library. Some rights reserved.

Nō te taenga ki te tau 1840, kua kore katoa atu tētahi 40% o ngā rākau o ngā motu nei.

Kua waerea e ngāi Māori ētahi wāhi nui whakaharahara hei whakatupu kai hei hoko ki ngā manene noho mai. Nā ngā manene Pākehā i tuatua, i tahu te ngahere — hei oranga kau mō ō rātou whānau. Ka keria ō rātou māra, ka whāngaia ā rātou kararehe, ka hangaia he whare rākau, ka tukua hoki he rākau ki tāwāhi.

By 1840, nearly 40% of the country's trees were gone.

Māori had cleared large areas to grow food to sell to the settlers. European settlers felled and burned more forest — simply to survive. They gardened and grazed animals, built wooden houses and exported timber.

Group at a farm in Winiata.

Image credit: Maori group at a farm in Winiata, 1894 by Edward George Child. Ref: 1/2-032309-G Alexander Turnbull Library. Some rights reserved.