Read a story about our colonial bird trade

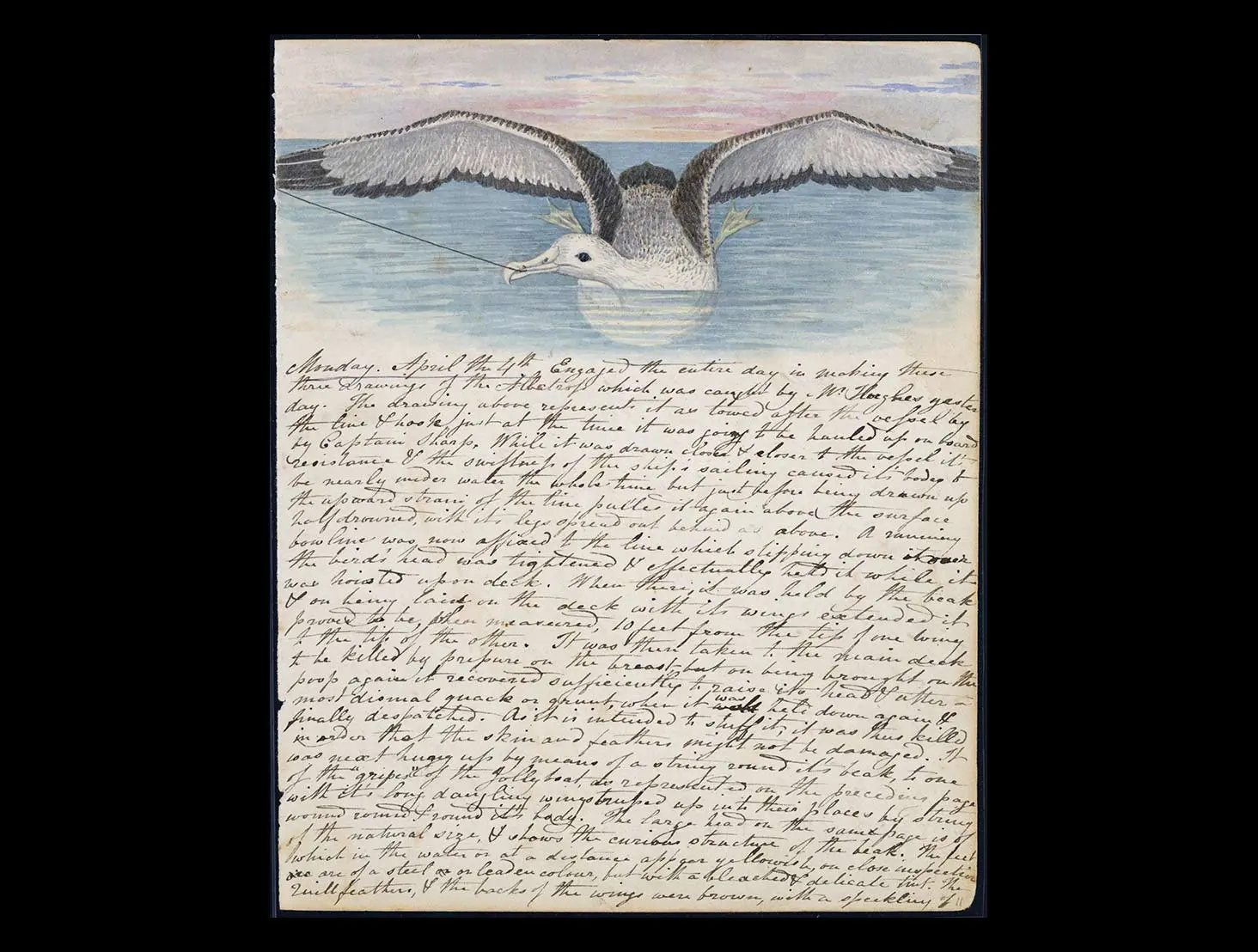

This poignant and exquisitely drawn image illustrates a migrant’s diary entry about the capture of a toroa (albatross) from the ship Clifford during its voyage to New Zealand in 1842. John Waring Saxton (1807–1866) gives a graphic description of how the toroa was hauled on deck half-drowned and then crushed to death. He goes on to write, ‘As it is intended to stuff [the albatross], it was thus killed in order that the skin and feathers might not be damaged.’

The killing of toroa by passengers and crew on ships traversing the oceans appears to have been relatively common, if mostly opportunistic. But this event was indicative of a seemingly insatiable appetite among European travellers to ‘new world’ countries like Aotearoa for hunting and selling manu (birds), some live but most dead, for avid collectors at ‘home’.

For Māori, as for indigenous cultures worldwide, manu were and are taonga — as messengers, augurs and teachers, and they featured prominently in pūrākau (traditional knowledge stories). New Zealand’s bountiful manu were not only a source of food and prized for adornment, but were also indicators of the mauri (life force) of the taiao (natural world).

In country after country where indigenous people had long lived in coexistence with their bird populations, new arrivals — visitors and colonists alike — plundered the exotic creatures, and there was no shortage of willing buyers. Manu were collected and traded by both individuals and institutions such as museums. Feathers were also highly sought after as fashion accessories, as well as for use in trims and embellishments for garments. As demand exploded, manu became commodities and their populations were decimated.

It is not known exactly how many of New Zealand’s unique manu were hunted and exported around the world, but the number has been described as astronomical. Taxidermists preserving specimens operated throughout the country, feeding this trade. It wasn’t until 1922 that a complete ban on hunting most native manu in New Zealand came into effect.

Today, toroa continue to be harmed by human activities, most commonly as fisheries by-catch. The Department of Conservation estimates that a million seabirds drown in drift nets each year in New Zealand territorial waters, and toroa are frequently caught on hooks set by commercial longliners.

Story written by: Rene Burton and Erena Williamson

Copyright: Turnbull Endowment Trust

Find out more

Read connected stories from Te Kupenga:

Explore the Alexander Turnbull Library collections further:

Topic Explorer has:

Many Answers has:

Want to share, print or reuse one of our images? Read the guidelines for reusing Alexander Turnbull Library images.

Curriculum links