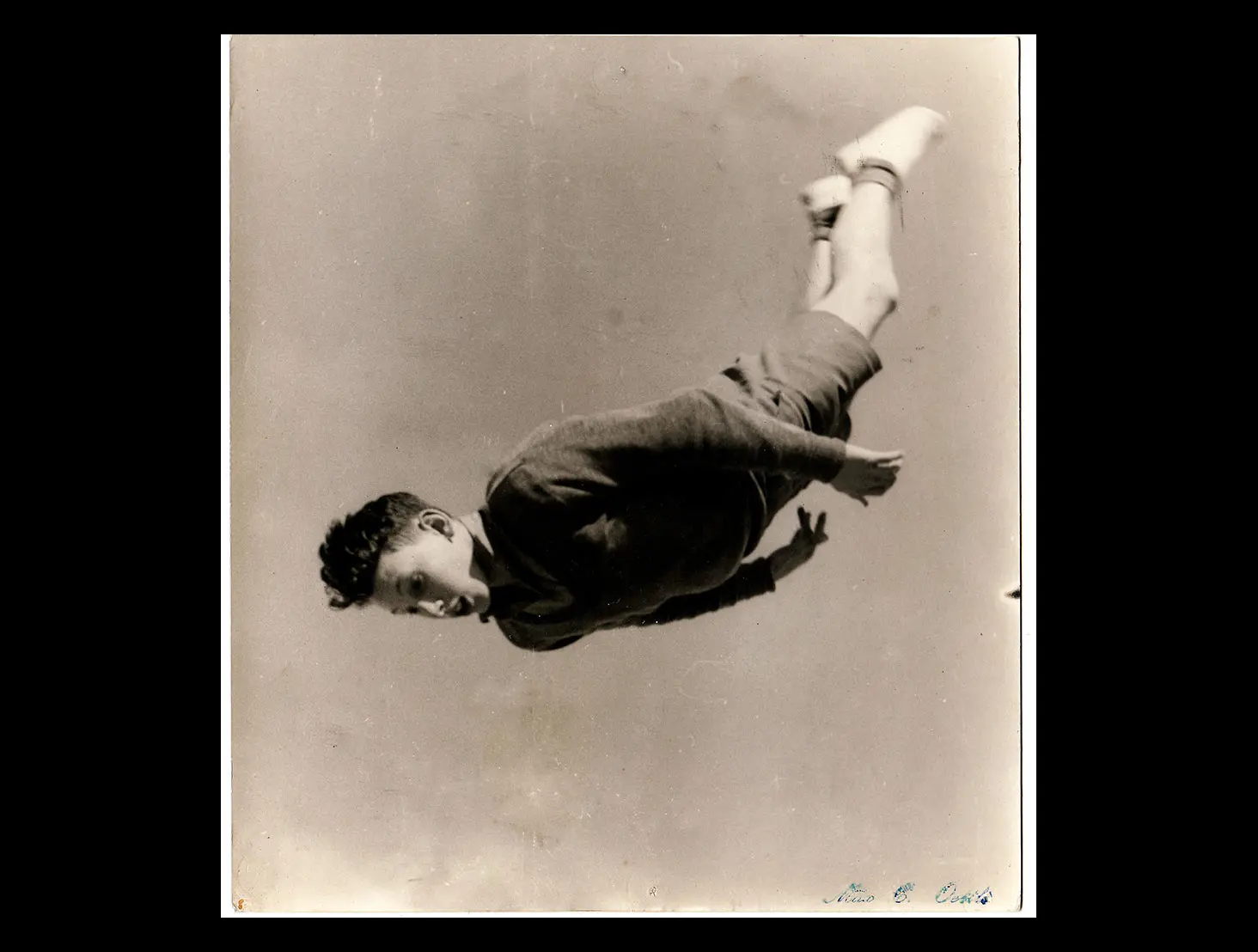

Image credit: ‘Kevin diving’, Fairfield College, Hamilton, 1964 by Max Christian Oettli. Ref: PADL-001331 Alexander Turnbull Library.

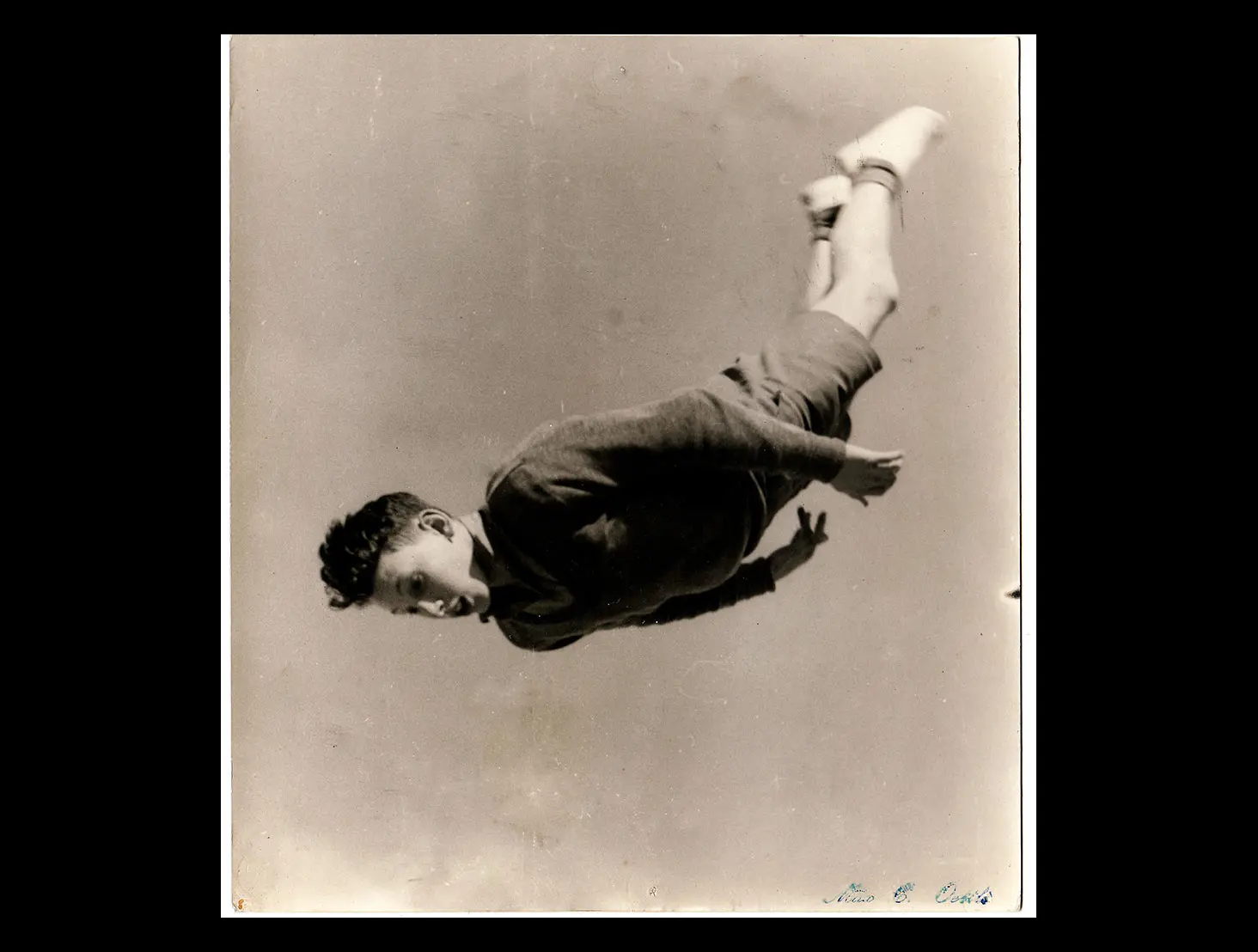

Image credit: ‘Kevin diving’, Fairfield College, Hamilton, 1964 by Max Christian Oettli. Ref: PADL-001331 Alexander Turnbull Library.

In the early 1900s, physical education (PE) in schools had a nationalistic approach. Later, PE focused more on the individual student and the qualities of movement (such as trampolining). Find out more by exploring our collections and curated resources.

Physical Education, phys ed, PE, or whatever it was called at your school, was something we all had to do. Some of us loved it, some of us loathed it, but most of us just did it. Why? Because we had to; it was compulsory. Why? Because it was good for us.

In the early 1900s, the commonly held belief that a healthy body ensures a healthy mind drove physical education in New Zealand schools. In the years leading up to the First World War, that approach was all about fitness and military prowess (the ‘healthy body’) and imperialistic morals and ideals (the ‘healthy mind’).

Physical education was focused on boys and largely took the form of military training, with marching, drills, fake battles and shooting instruction. From 1913, however, it became compulsory for all students. Healthy children continued to be seen as essential to the strength and survival of the nation, and while the boys kept on marching, the girls undertook less explicitly ‘military’ exercises such as stretching and lifting dumbbells (undertaken in full school uniform, including stockings). This nationalistic approach was a key part of school life until the end of the Second World War, when educationalists began to criticise it as endangering children’s individual moral, physical and emotional development.

Philip Smithells, the Education Department’s Superintendent of Physical Education, took a similar view. In the 1940s he revamped both the primary and secondary school syllabuses, downplaying ‘all-conquering athleticism’ and the connection between the healthy body and the healthy mind. Instead, he stressed the responsibility teachers had to all children as individuals, including those with physical disabilities, those with poor motor skills and ‘average’ performers. He even established remedial clinics to help with this. In addition, Smithells emphasised the aesthetic qualities of movement in his syllabus, mainly through dance and gymnastics, which included trampolining.

The current New Zealand Curriculum contains elements of both approaches — physical education for society, and physical education for the individual. Unlike the binary models of the past, they coexist and are considered equally important.

As for Kevin, the flying Waikato schoolboy captured in this image by Swiss-born photographer Max Oettli (b. 1947), we don’t know whether he loved or loathed phys ed. But in this moment of trampoline magic, at least, he looks as if he’s having a good time.

Story written by: Indira Neville

Copyright: Turnbull Endowment Trust

Swiss-born Max Oettli took up photography as a teen in Hamilton and became a career photographer, capturing slice-of-life moments from the 1960s to the present. He deposited his archive with the Turnbull in 2004.

Explore the Alexander Turnbull Library collections further:

Topic Explorer has:

Want to share, print or reuse one of our images? Read the guidelines for reusing Alexander Turnbull Library images.

Tikanga ā-iwi:

Te whakaritenga pāpori me te ahurea

Te ao hurihuri.

Te Takanga o Te Wā (ngā hītori o Aotearoa):

Whanaungatanga.

Social sciences concepts:

Identity, culture, and organisation

Continuity and change.

Aotearoa New Zealand's histories:

Colonisation and its consequences

Relationships and connections between people.