School libraries in Aotearoa New Zealand — 2021

Read the report on the 2021 national survey of school libraries in Aotearoa New Zealand. Find out about school library staffing, collections and budgets, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Executive summary

Background

This is the third report from an ongoing series of national surveys of school libraries in Aotearoa New Zealand that started in 2018. The surveys are a collaboration between the National Library of New Zealand Services to Schools, the School Library Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (SLANZA) and the Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (LIANZA).

The information gathered through this survey helps us establish a common understanding with stakeholders about:

the current make-up of the school library workforce

expected changes in the school library workforce

trends relating to school library collections and resources

school investment in library collection development

the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on school libraries.

Summary of findings

Library staff employment arrangements

Our findings show differences in employment arrangements for responding schools, across school types.

As student year levels increase, the percentage of library staff working part-time decreases.

19% of primary and intermediate school library staff work in more than one part-time position.

Most school library staff work during term-time only (40 weeks per year).

80% of respondents thought it unlikely their hours would reduce. Respondents who said it was likely their hours would reduce gave budget pressures as the main reason.

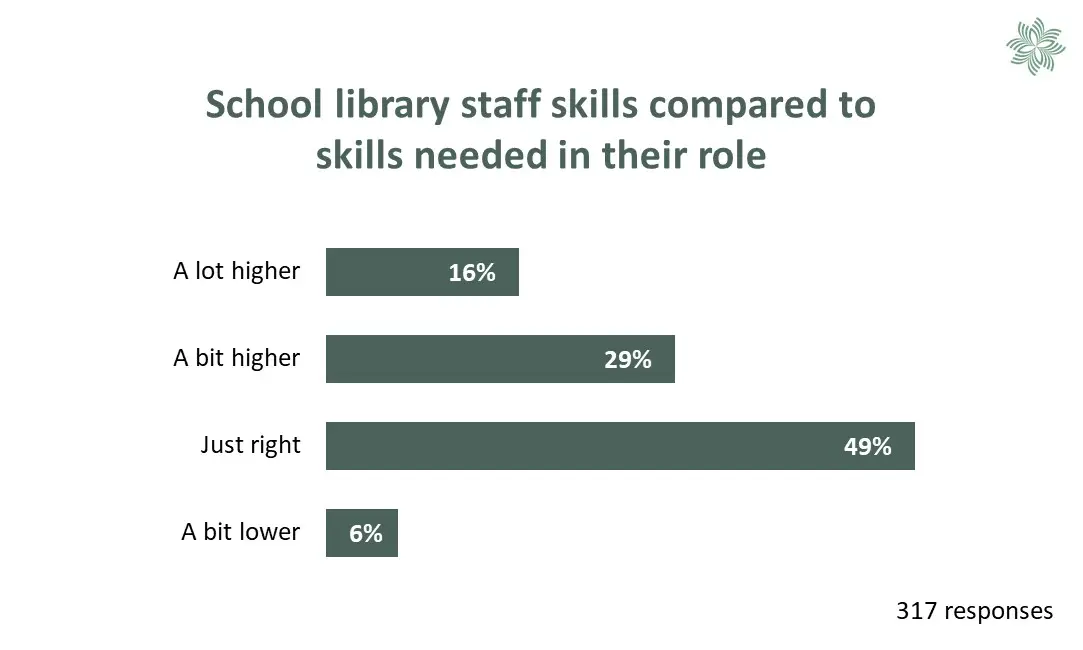

49% of school library staff said their skills are a good match for the requirements of their current role. 45% said their skills are higher.

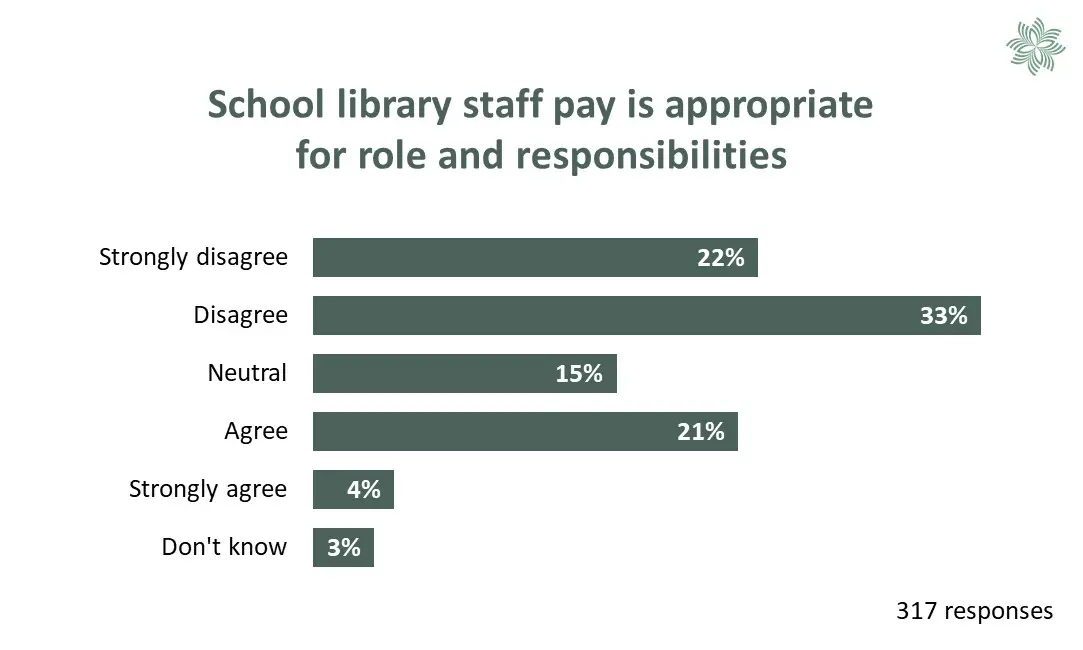

25% of school library staff felt their pay was appropriate for their role and responsibilities and 55% felt it was not.

Almost all school library staff said they enjoy working in the school library and most say they'd like to continue in the role. But 21% said they plan to retire in the next few years, and 10% were actively seeking other work.

School library staff respondents' qualifications are varied. They include certificates and diplomas, degrees and post-graduate qualifications in Library and Information Studies (LIS) and other fields. Qualification levels vary across school types, with primary school library staff most likely to hold no qualifications.

Support and professional learning

52% of school library staff respondents said that they are supported well by their school's leadership team, but 26% said they are not. A common theme from respondents' comments was that they are trusted to ‘get on with things’ but support is available if needed.

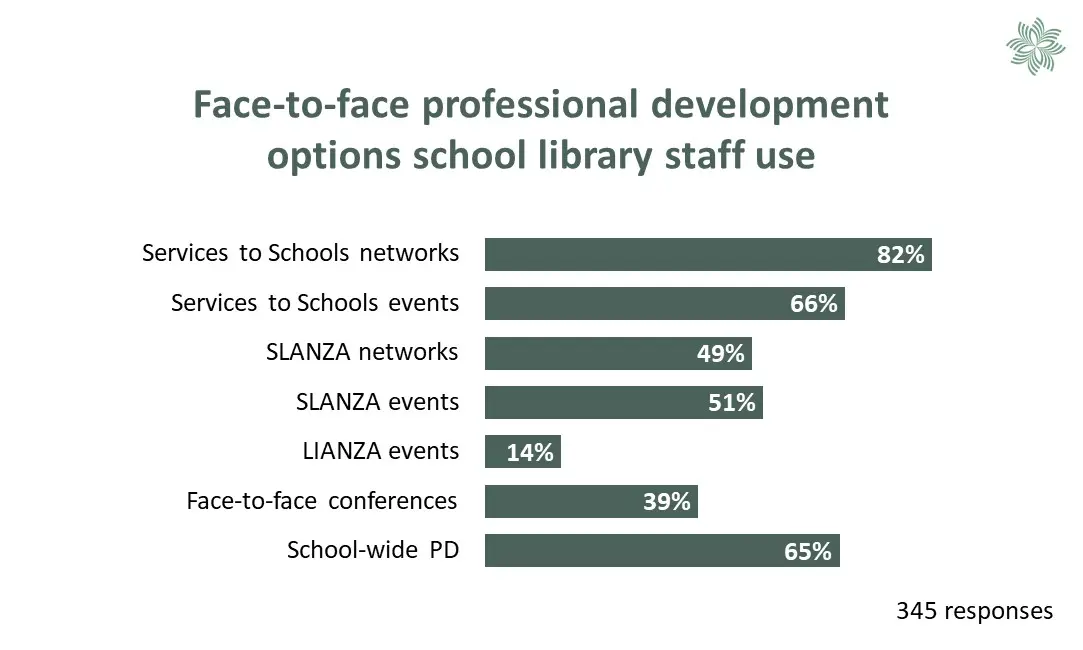

We presented 22 options for continuing professional development and asked respondents how often they use each one. Findings show that the most popular options are:

National Library Services to Schools' network meetings, face-to-face and online professional development, and website

the SLANZA website

social media and blogs, the school library listserv, peer-to-peer support

school-wide professional development.

Library collection holdings and trends

We asked respondents to tell us about their collection holdings across 3 broad categories — print resources, digital resources and physical items.

For all responding schools, the bulk of current holdings is print items. Responding secondary schools are more likely than other schools to include digital resources in their collections. Physical items are most likely to include:

mobile devices such as laptops that students can borrow, particularly in secondary schools

puzzles and games, craft supplies and materials.

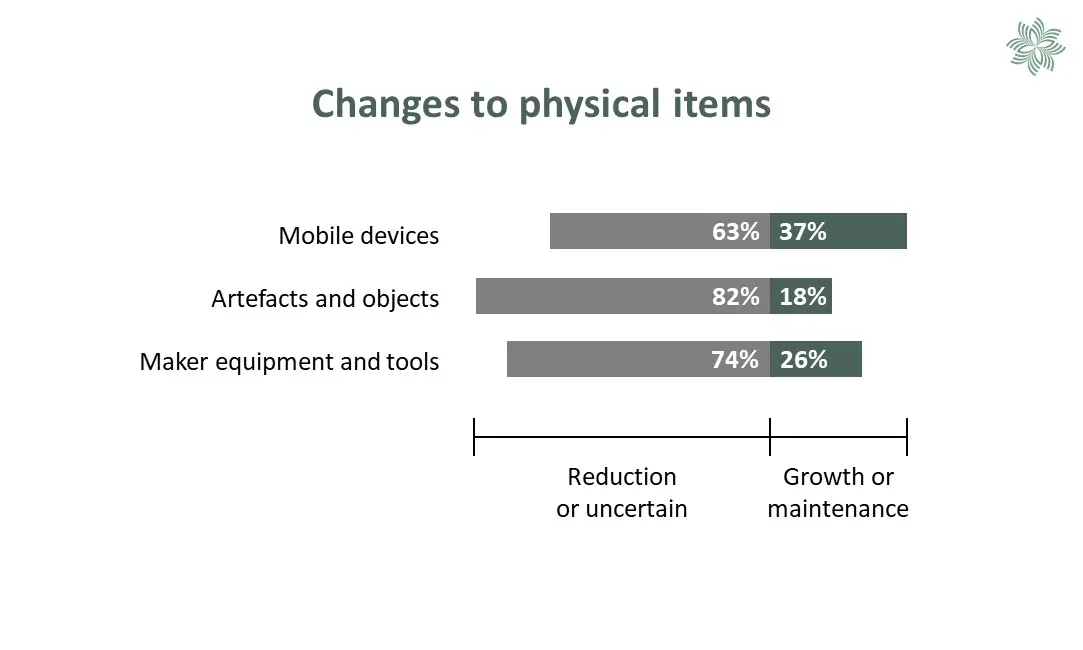

Mobile devices, artefacts and objects, or maker tools and equipment make up less than 1% of responding schools' collection holdings.

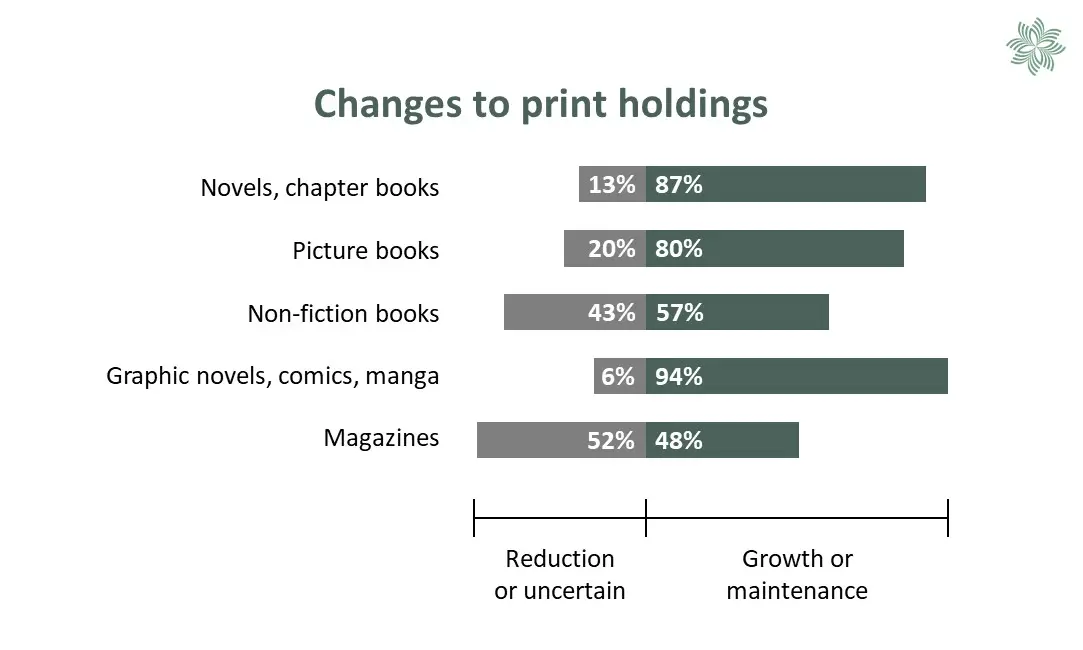

Respondents showed the least uncertainty in responses about the future of print formats. Within this category, respondents expect only non-fiction books and magazine holdings to reduce. Respondents expect graphic novels, comics and manga holdings to grow more than any other formats.

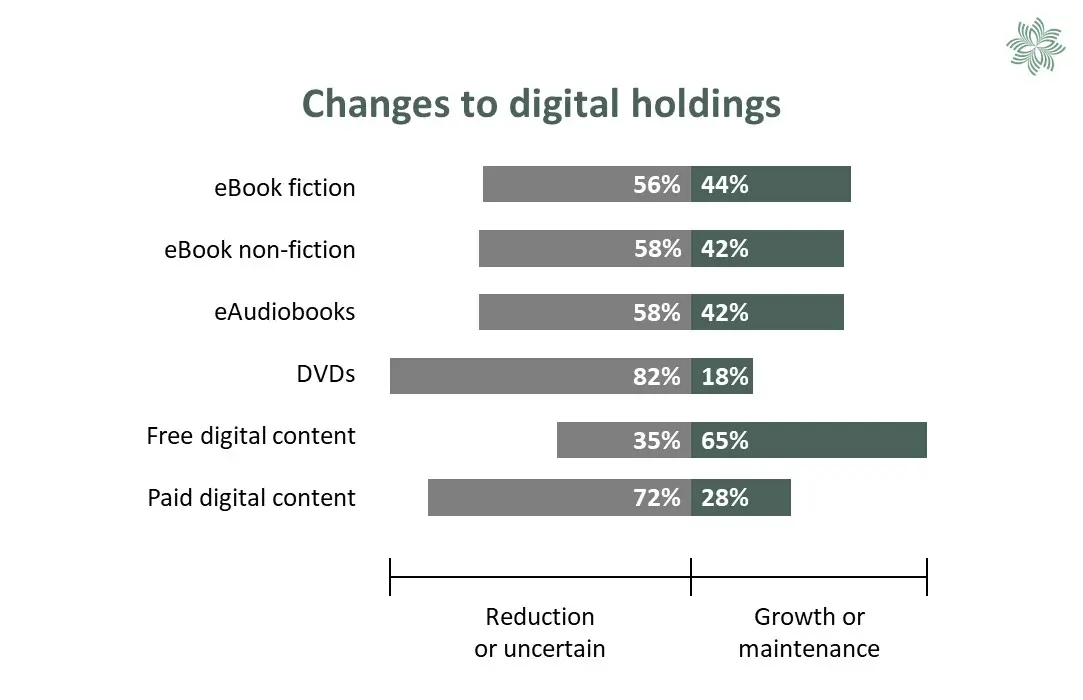

There is more uncertainty about holdings of digital resources. Respondents expect holdings of freely-available digital content to grow. eBook and audiobook holdings are expected to remain static and DVD holdings to decline.

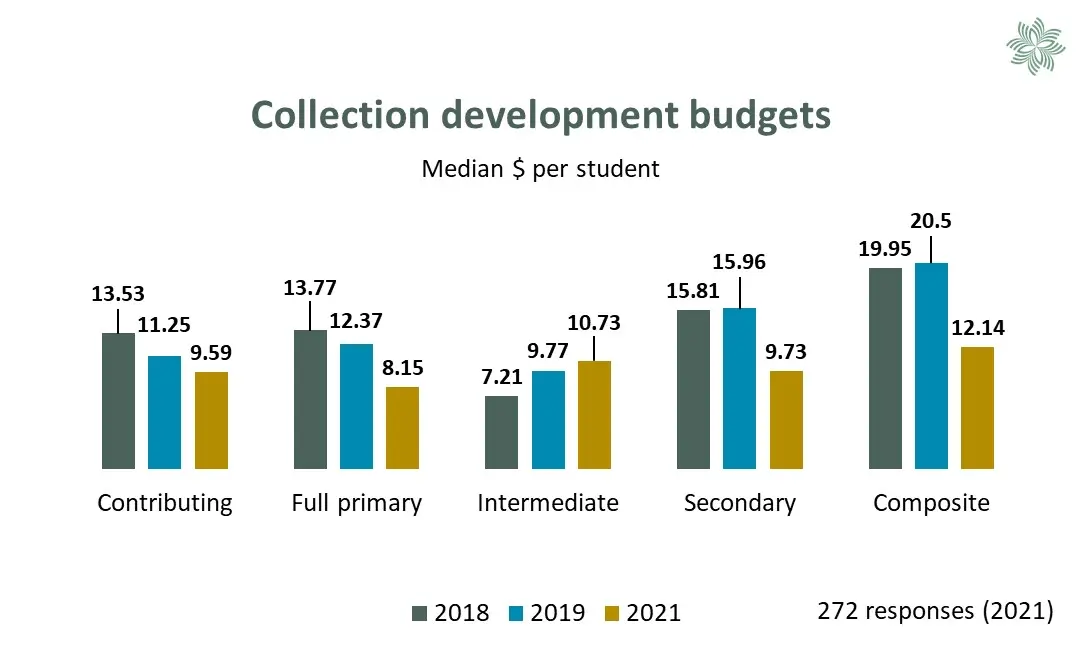

Collection development budgets

Across all responding schools, the 2021 median budget was $11.48 per student. This is a drop of $2.48 per student since 2019.

There is still some variation between school types, although this has reduced with the range now being $8.15 to $12.14 per student. In 2019, the range was $9.77 to $20.50 per student.

Most respondents (63%) said their 2021 collection development funding was the same as the previous year.

COVID-19 pandemic and school libraries

We asked about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on 4 aspects of library provision:

library staff hours

collection development funding

collection holdings

library services.

Aside from library services, most respondents reported no change in library provision due to the pandemic at the time of the survey.

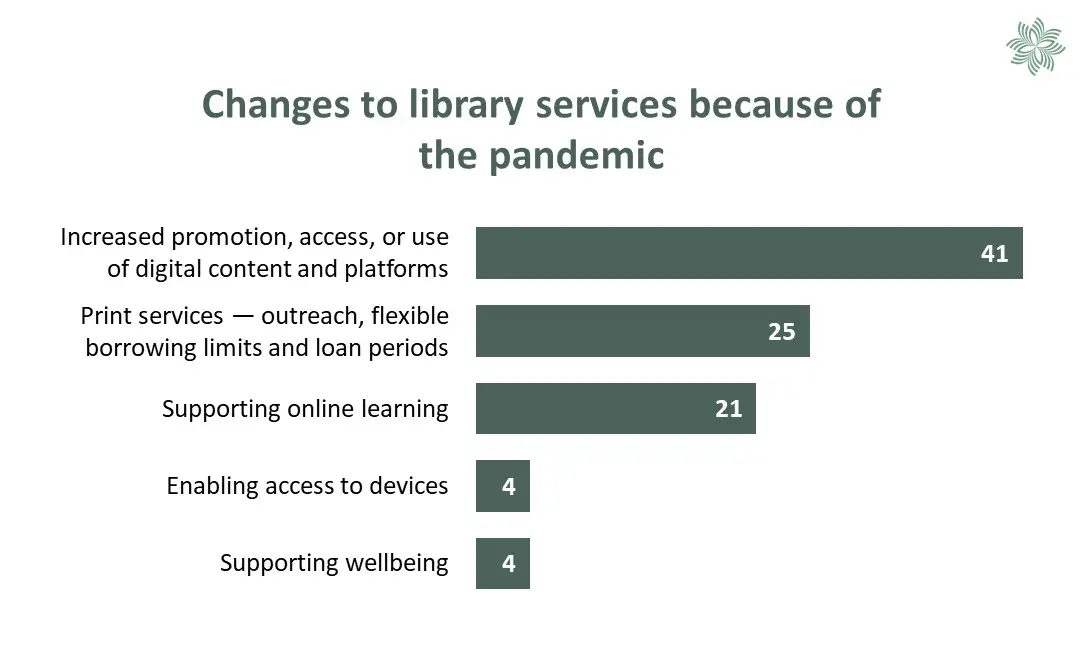

Public health measures did have a major impact on library services and, consequently, on the work library staff were doing.

Respondents' comments described how they supported reading and learning at home or online by:

adapting or extending borrowing services for print items

promoting and providing access to digital resources

reading to or with students.

Using this report

It is up to each school and kura to decide the levels of library staffing, funding and other resourcing they need to achieve the goals and aspirations they have for all their learners.

We hope that this report can help guide schools in making those decisions. The findings in the report are best used alongside the other school library development resources and support National Library, SLANZA and LIANZA provide.

We recommend that National Library Services to Schools, LIANZA and SLANZA:

share the findings with stakeholders, especially in the education and library sectors

use the findings to guide the development of our services that support school libraries and school library staff

encourage further research stemming from the findings of this survey

work together to address concerns raised in this report about school library provision

survey schools again to track changes over time and to deepen our understanding of areas identified for particular focus.

Introduction

Purpose and scope

This is the third report from an ongoing series of national surveys of school libraries in Aotearoa New Zealand that started in 2018. The surveys are a collaboration between the National Library of New Zealand Services to Schools, the School Library Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (SLANZA) and the Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa (LIANZA). Through these surveys, we aim to add to our existing evidence base about the nature of school libraries in New Zealand. The surveys help inform our organisations as we prioritise, plan and deliver services to school libraries.

The information gathered through the surveys helps us establish a common understanding with stakeholders about:

the current make-up of the school library workforce

expected changes in the school library workforce

trends relating to school library collections and resources

school investment in library collection development

the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on school libraries.

The 2021 survey builds on information gathered in 2018 and 2019. We did not conduct a survey in 2020.

Survey design and implementation

All 3 surveys included questions about:

library roles and hours

library staff qualifications and professional memberships

collection development budgets and sources of funding

expected change to holdings of various formats.

In the 2019 and 2021 surveys, we asked about:

library staff's current employment arrangements

factors influencing library staff decisions about their current and future work

the relationship between library staff skills and pay

support and continuing professional development for those in school library roles

collection holdings, including a detailed breakdown by format type.

In the 2021 survey, respondents could also describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on:

library staff hours

collection development funding

collection holdings

library services.

Survey implementation

The 2021 survey link was shared with schools through:

the New Zealand school library email listserv

National Library’s Services to Schools newsletter

school network contact lists and social media.

SLANZA and LIANZA also shared the link with their members.

Responses were collected between 1 and 29 November 2021.

Sample size, questions and demographics

We received 647 responses to the 2021 survey. We excluded:

98 incomplete or duplicate responses

30 unidentifiable responses to ensure unique responses for analysis of school-level questions.

This left a core sample size of 519 — representing approximately 20% of New Zealand schools and a higher response rate than previous surveys (19.7% in 2018, 14% in 2019).

Questions

349 respondents who were school library team members employed as support staff were asked about their employment arrangements and support.

All survey questions were optional apart from school type and respondent's role. This means that the number of responses varies from one question to another. The percentages shown in our findings are calculated on the number of responses to specific questions.

Demographics

Survey response demographics align with school demographics by region. Full primary schools (years 1–8) are under-represented by approximately 10%. Secondary schools are over-represented by a similar amount. Deciles 1 and 2 schools are under-represented, and deciles 7 to 10 are over-represented.

Respondent characteristics

68% of respondents were school library staff (library assistants, librarians, library managers and teacher-librarians).

44% of these staff work extra roles (often teaching assistants/learning support or administration/office support positions). Most who chose ‘other’ as their role are assistant or deputy principals.

Table 1: Respondent roles

Role(s) | School library staff | Teacher librarian | Other support staff | Teacher | Principal | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Main role | 349 | 25 | 74 | 59 | 23 | 19 |

Employed in any additional role(s) | 155 | 12 | 58 | 44 | 10 | 15 |

Analysis and reporting

In this report, we discuss the main findings from each section of the survey. Data are generally presented as aggregated totals. Where data show a clear difference between school types (as listed in Table 2 below), we provide a more detailed breakdown.

Table 2: Year levels for New Zealand school types

School type | Year levels |

|---|---|

Contributing (primary) | 1–6 |

Full primary | 1–8 |

Intermediate | 7–8 |

Secondary | Within the range 7–13+ |

Composite | 1–13+ |

Themes and more information

We have coded the free-text responses to summarize the main themes that emerge.

We may be able to provide individual schools or organisations with a more detailed analysis on request, for example, based on school size, decile or isolation factor.

Library staffing and employment

We presented a range of volunteer and paid roles and asked respondents to select which of these work in their library. There were 466 responses to this question. Only 15 chose ‘none of these roles’. For all other roles respondents selected, we asked how many hours of work each has per week.

We asked school library support staff 2 extra questions about their hours:

the likelihood their hours would reduce in the next 12 months

what changes they'd make to their hours, if possible.

Roles and hours

Across all responding schools, 71% use student volunteers. Intermediate and secondary schools use student volunteers the most.

Responding primary schools are twice as likely as intermediate and secondary schools to have a ‘teacher with library responsibility’ role.

434 unique schools provided information about hours of work. As school rolls increase, so do paid library staff hours at responding schools. Only schools with more than 300 students have paid library staff working 30 or more hours per week.

Table 3: Responding schools’ average roll and staff/volunteer hours

School type | Average roll | Average paid hours per week | Average volunteer hours per week |

|---|---|---|---|

Contributing and full primary | 337 | 15 | 10 |

Intermediate | 561 | 27 | 14 |

Secondary | 920 | 45 | 20 |

Composite | 503 | 36 | 12 |

The likelihood of hours reducing

We asked school library staff if they thought their hours would reduce in the next 12 months. There were 295 responses to this question. 80% of responses said it's unlikely or very unlikely.

Respondents who said it was likely their hours would reduce gave budget pressures as the main reason. Comments mentioned these pressures were because of:

loss of international fee-paying students due to the pandemic

falling school roll

lack of support for the library within the school.

Preferred changes to hours

213 respondents left comments about preferred changes to their hours. 83 said they do not see a need for their hours to change. But most (120 respondents) said they'd like longer paid hours. The main reasons given for wanting longer hours were:

a lack of time to get things done, currently

to provide better support for teaching and learning

to reduce current levels of unpaid work.

Some comments

The librarian hours were cut by an hour a day this year and it is very difficult to stay ahead of my jobs … I am also having difficulty in keeping up with repairs, covering, researching new resources etc.

With a change in leadership, there has been a change in hours for the teacher aide (fewer hours). There is not the commitment to ongoing collection development, staff support, innovation etc.

Very thankful for the hours I do have but could use another 5 hours per week in order to stay on top of ‘behind the scenes’ work as I am with classes for most of the allotted 35 hours.

Employment arrangements

Part-time versus full-time

There are clear differences in respondents' employment arrangements across school types. 318 respondents answered the question about part-time and full-time work.

84% of primary school staff respondents work part-time — 65% in just one school library and 19% work in more than one position.

69% of secondary school staff respondents work full-time in just one library. A further 27% work part-time in one library and 4% work in more than one position.

Approximately half of intermediate and composite school library staff work full-time in one school library.

Table 4: School library staff part-time and full-time employment

School type | Part-time in just one library (%) | Part-time in more than one position in the school (%) | Part-time in more than one library (%) | Full-time in just one library (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Contributing and full primary schools | 65 | 15 | 4 | 16 |

Intermediate schools | 33 | 14 | 5 | 48 |

Secondary schools | 27 | 2 | 2 | 69 |

Composite schools | 44 | 4 | n/a | 52 |

Term-time or full year

301 school library staff answered the question about working term-time only (40 weeks) or for the full year (52 weeks). 278 said they work during school term time only. Library staff in composite schools are more likely to work 52 weeks per year than staff in other school types.

Table 5: School library staff employed term-time only

School type | Employed term-time only (%) |

|---|---|

Contributing and full primary schools | 97 |

Intermediate schools | 82 |

Secondary schools | 92 |

Composite schools | 75 |

My library hours are flexible, I am full time with multiple roles and how many hours spent doing library tasks depends on other jobs and library tasks.

Themes in comments

We received 133 comments with more information about school library roles and hours. The main themes of the comments are listed below.

46 respondents indicated that their library staff hours are inadequate. 20 respondents said they do extra work unpaid at present.

25 respondents said library staff roles are often split between the library and other duties in the school.

14 respondents mentioned that volunteer hours fluctuated (students and adults). Reasons included unreliability and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our library is a valued asset within the school so I don't believe hours would be reduced at all.

I expect staffing to continue to be stable, but we will have a new principal later in the year who might have a different idea.

If the pay rate goes up with the equity deal the union is working on, my hours will be cut.

I am leaving this job … and I suspect this will play a role in a reduction of hours in the future. The principal may take the opportunity to change the nature of the roles of library and library staff within the school.

Skills and pay

We asked library staff to compare both their skills and pay with the requirements and responsibilities of their current role. 317 respondents answered these questions.

49% said their skills are just right for their current role. Of the remainder:

45% said their skills are a bit higher (29%) or a lot higher (16%) than what the job requires.

only 6% said that their skills are lower than what's needed in their current role.

55% of respondents feel that they are not paid appropriately considering their role and responsibilities. 25% agree that they are paid appropriately.

Figure 1: School library staff skills compared to skills needed in their role

Table 6: School library staff skills for their role — break down by school type

School type | Higher (%) | Just right (%) | Lower (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Contributing and full primary | 38 | 53 | 9 |

Intermediate | 61 | 39 | n/a |

Secondary | 48 | 49 | 3 |

Composite | 59 | 32 | 9 |

Figure 2: School library staff pay is appropriate for role and responsibilities

Table 7: School library staff pay is appropriate for role and responsibilities — break down by school type

School type | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) | Don't know (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Contributing and full primary | 26 | 18 | 52 | 4 |

Intermediate | 39 | 9 | 43 | 9 |

Secondary | 22 | 14 | 62 | 2 |

Composite | 27 | 23 | 45 | 5 |

Comments about skills and pay

108 respondents commented on their pay. Only 13 were satisfied with it. 25 just said that they are underpaid.

The remaining 70 explained why, and these comments fall into 3 broad themes:

pay grades and rates do not reflect the responsibilities inherent in the role

pay rates do not recognise the individual's skills, qualifications or experience

disparity with other support staff while the school librarians' pay equity claim is unresolved.

Pay does not reflect skills required or responsibility, also now compares very unfavourably with teacher aide pay.

My principal recognized my skills in librarianship and research information teaching and placed me in a higher grade to reflect the work I do.

Librarians' work is undervalued and consequently underpaid. The current remuneration in no way reflects the depth and breadth of the scope of our work.

I have postgraduate English and history degrees, but no formal librarian qualifications, but I'm essentially on just above minimum wage.

Factors influencing employment decisions

We presented a variety of factors and asked library staff to indicate which ones influence their decisions about current and future work. 316 respondents answered these questions.

Current employment

Respondents could select more than one factor, so percentages will add to more than 100.

94% of respondents said they enjoy working in the school library.

72% indicated that hours aligning with their needs is a factor (bear in mind most of the respondents work term-time only).

58% said they live in the local area.

57% expressed an interest in working with young people.

34% said their children attend or used to attend, the school where they work.

Respondents could include comments to clarify their reasons. 17% of respondents' comments mentioned their passion for reading.

I absolutely love my job. I love encouraging reading with the intermediate age group.

I find the work rewarding and love seeing our students develop a love of reading. I also enjoy creating a sanctuary for many of our students who find the school day stressful.

Only option for part-time librarian job nearby. I have small children, so school holidays off is the biggest benefit as it gives much needed work/life balance.

Future plans

80% of respondents said they'd like to continue working in their current school library role.

28% said they would consider other library work involving services for children or youth.

14% would consider other library work not involving children or youth.

10% are currently looking for work outside of libraries.

21% of respondents said they plan to retire in the next few years.

Comments here backed up earlier responses. 18% of comments mentioned age as a deciding factor. The same number cited dissatisfaction with the pay or opportunities to earn more elsewhere.

A major factor for whether I would stay in this role is if my hours were cut again. It would make life difficult considering my husband is near to retirement and we would be relying on my wages.

As my children get older I would like to work more hours, and at some point, I would like to get back into the public library system.

Certainly, the low salary is a concern. I'm in my mid-50s and need to think about saving for retirement.

COVID has made us all rethink our priorities. I intend to ‘retire’ early and either do a few hours in a similar library (out of the city) or … something … not work formally at all.

Staff qualifications

We asked school library staff to tell us about the qualifications they hold. 313 respondents answered this question.

The responses show that school library staff have a wide range of qualifications. 30% hold a sub-degree level Certificate or Diploma in Library and Information Studies (LIS). 25% of respondents hold more than one qualification. And 25% of respondents say they have no qualifications.

There are clear differences in respondents' qualifications across school types. As student year levels increase, the percentage of library staff with no qualifications decreases. 25% of respondents hold more than one qualification.

Table 8: School library staff with no qualifications

School type | Number of responses | No qualifications (%) |

|---|---|---|

Contributing | 79 | 38 |

Full primary | 62 | 31 |

Intermediate | 23 | 30 |

Secondary | 137 | 14 |

Composite | 22 | 9 |

Table 9: School library staff with qualifications in library and information studies (LIS)

School type | Sub-degree level certificate or diploma (%) | Degree (%) | Post-graduate qualification (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Contributing | 23 | 3 | 4 |

Full primary | 18 | 5 | 0 |

Intermediate | 22 | 9 | 13 |

Secondary | 35 | 6 | 14 |

Composite | 41 | 0 | 5 |

Table 10: School library staff with qualifications in other subject areas (not LIS)

School type | Sub-degree level certificate or diploma (%) | Degree (%) | Post-graduate qualification (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Contributing | 16 | 22 | 8 |

Full Primary | 23 | 21 | 15 |

Intermediate | 17 | 35 | 22 |

Secondary | 14 | 35 | 13 |

Composite | 23 | 45 | 18 |

Themes in comments

64 respondents added comments about qualifications, registration or professional memberships. The main themes of these comments were:

the costs (money and time) of studying or registration outweigh the benefits

experience and professional development are as valuable as formal qualifications.

18 respondents reported positive experiences with study and professional development providers.

Although I do not have formal library qualifications, I am trained as an English teacher, an ESOL teacher and an adult literacy teacher.

I think my experience exceeds a formal qualification and professional memberships are actually unnecessary for a school our size.

I have considered getting a qualification but there's not much incentive pay wise.

I would like to study more but financially I cannot support this and I can't progress wage-wise so there is little motivation.

Would have loved to have completed my library diploma or degree but the remuneration in return is terrible. It would take almost 10 years to recover the cost of the diploma alone on the current remuneration scale (not including the hours of personal time to do said paperwork) — by then I'm almost ready to retire.

Support and continuing professional development

Support from the leadership team

We asked school library staff about leadership team support for their role. 313 respondents answered this question.

52% of respondents agree that they are well supported by their leadership team, but 26% said they are not.

Themes in comments

Respondents could also add comments about support for their role. 115 comments were recorded, 52 of them from respondents who felt well supported.

44 respondents said that support is limited or qualified in some way. The main themes from this group of comments were:

library staff are trusted to work independently and ‘get on with things’, but that support is available if needed

support can be hampered by a lack of funding, time and resources

other staff have little to do with the library staff because of a lack of understanding of the role or importance of the library.

I am very supported in my role and am able to raise my hand and question when things are likely to impact on our ability to function.

I work very autonomously at school — I would like a bit more support from my school colleagues.

The students support me … they try to beat the door down if I'm not open in time for breaks! SLT aren't library people at all and see me as a childminder and provider of a venue for big meetings and social gatherings. On the whole, the teachers do express support and state openly that I am a valuable asset, but that doesn't translate into utilising the resources.

There have not been many professional development opportunities this year, probably because of COVID restrictions. There haven't been very many online PD opportunities either, I would have liked to have taken advantage of online learning.

Very little understanding of what I do and can offer. Generally supported but recent attitudes to the importance of literacy and critical literacy have been disappointing.

My principal is pretty open to funding for training etc as long as it can be adequately justified in a proposal and he can see you putting your learning into practice.

Continuing professional development

We showed respondents a range of learning options and asked how often they use each one.

Face-to-face professional development options included:

school-wide professional development (not library-specific)

local network meetings, learning events and workshops offered by the National Library, LIANZA or SLANZA

in-person conferences.

These options showed the most variation in uptake, as shown below. The most-used option is network meetings facilitated by National Library Services to Schools.

Figure 3: Face-to-face professional development options school library staff use

Other learning options presented included:

participating in online learning such as courses, webinars and meetings

reading online sources of information including websites, blogs or journals

participating in informal, social options such as peer support, email lists and social media.

Responses were consistent for all these other learning options:

about 25% of respondents use them often

about 40% use them sometimes

about 35% never or almost never use them.

Table 11: Professional development options used sometimes or often

Continuing professional development options | Use sometimes or often (%) |

|---|---|

School-wide professional development | 65 |

Services to Schools networks | 82 |

SLANZA networks | 49 |

Services to Schools events | 66 |

SLANZA events | 51 |

LIANZA events | 14 |

Face-to-face conferences | 39 |

Services to Schools online courses | 65 |

SLANZA online courses | 65 |

Services to Schools webinars | 64 |

SLANZA webinars | 64 |

LIANZA webinars | 64 |

Services to Schools website | 66 |

SLANZA website | 66 |

LIANZA website | 64 |

Professional journals | 60 |

School library blogs | 65 |

Peer-to-peer support — school librarians | 65 |

Peer-to-peer support — public librarians | 65 |

School library listserv | 65 |

Other listservs | 65 |

Social media | 65 |

Collection holdings

We asked participants questions about 3 broad categories of items:

print resources, including fiction and non-fiction texts and graphic formats

digital resources, including eBooks and eAudiobooks and links to free or paid content

physical items including mobile devices, objects and artefacts, tools and other equipment.

We also asked participants to say how they expected their holdings of each format or item type to change.

Size of collection

We asked respondents to provide a single figure for their total collection size. They could also provide a breakdown of the number of items held for specific formats or types. Many schools provided both total figures and a breakdown by format and type.

Data in this section are approximate because:

COVID-related school closures meant that some respondents could not retrieve exact data

some schools provided breakdown figures that do not sum to their single total figure.

Table 12: Average school roll and collection items per student

School type | Average school roll | Collection items per student |

|---|---|---|

Contributing | 393 | 19 |

Full primary | 326 | 20 |

Intermediate | 586 | 15 |

Secondary | 962 | 12 |

Composite | 410 | 24 |

Themes in comments

Respondents were able to comment on the size of their current collection. We received 116 comments. The main points noted were:

37% said the size of the collection was adequate or appropriate for their school roll

collection size is sometimes constrained by the physical space available to house it

limited budgets impact the ability to expand holdings to meet demand, for example, graphic novels.

We would like to increase our collection, especially biographies and fiction. We have removed our eBooks as they were not used enough to justify the cost of the subscription.

The book collection was downsized by 10% so that it could fit into a classroom. Size will now be determined by available space and not driven by needs of staff and students.

I am hoping to reduce the collection to 5500 books or less and make it a more attractive collection for the kids. At the moment there are too many books and it can be overwhelming for kids to know what to choose.

We rely heavily on National Library resources. Our students can also have a free digital membership in the local library. Some students have had access to print disability resources.

We have a small school roll and are growing our collection. Many books need to be replaced still but we are working on it.

We are currently reducing the size of our collection due to space constraints in our modern learning environment.

Our collection is quite vast, we have a large space to fill, we could do with replacing or updating some of our resources, and we are doing this as our budget allows.

Formats in collection

We asked about holdings of different format types. There were 297 responses to these questions.

For all school types, print resources still dominate current collection holdings. Secondary school libraries are more likely to have digital resources. Their collections also contain the highest proportion of digital resources.

Format holdings within our 3 broad categories (see above) vary between school types. For example, picture books make up approximately 25% of primary school collections. This drops to about:

9% for composite schools (years 1–13)

6% for intermediate

under 2% for secondary schools.

Graphic novels are a small part of library collections — less than 6% of holdings for all school types.

Table 13: Format types as a percentage of collection holdings

School type | Print (%) | Digital (%) | Physical items (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Contributing and full primary | 96 | 4 | <1 |

Intermediate | 90 | 10 | <1 |

Secondary | 80 | 19 | 1 |

Composite | 89 | 11 | <1 |

Table 14: Print holdings by format as a percentage of total holdings

School type | Novels or chapter books (%) | Picture books (%) | Non-fiction (%) | Graphic novels, comics or manga | Magazines (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contributing and full primary | 35 | 24 | 32 | 4 | 1 |

Intermediate | 47 | 6 | 30 | 6 | 1 |

Secondary | 37 | 1 | 35 | 4 | 3 |

Composite | 31 | 9 | 43 | 3 | 3 |

Table 15: Digital resource holdings by format as a percentage of total holdings

School type | eBook fiction (%) | eBook non-fiction (%) | eAudiobooks (%) | Free digital content (%) | Paid digital content (%) | DVDs (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Contributing and full primary | 2 | <1 | <1 | <1 | 0 | <1 |

Intermediate | 7 | <1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | <1 |

Secondary | 11 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

Composite | 6 | <1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Physical items

Respondents' holdings of physical items are almost exclusively mobile devices. The majority of these are Chromebooks or laptops, with fewer small devices such as iPads.

Very few primary school libraries provide mobile devices that students can borrow. As student year levels rise, so does the percentage of schools with mobile devices for loan. Most of the responding secondary schools with mobile devices hold fewer than 50.

There were 36 comments describing other objects, artefacts and tools in respondents' collections. Half of the comments mentioned puzzles and games. 38% described ‘maker’ tools and AV (audiovisual) equipment, media and print production.

Table 16: Percentage of responding schools with mobile devices students can borrow

School type and years | Schools with mobile devices (%) |

|---|---|

All primary schools (years 1–8) | <1 |

Intermediate schools (years 7–8) | 31 |

Composite schools (years 1–13+) | 50 |

Secondary schools (years 7–13+) | 63 |

Future changes to collection holdings

We asked respondents how they expect collection holdings of different formats to change. On the left of Figures 4 to 6, responses show uncertainty and reductions in holdings. On the right, are responses that show maintenance of current holdings, or growth.

Of the broad format categories above, respondents were least uncertain about print. Holdings of print formats (excluding magazines) have the strongest expected growth. Links to free digital content is the only other format type expecting similar growth.

Holdings of print non-fiction have the highest expected rate of reduction. Other formats expected to reduce are DVDs and print magazines.

Figure 4: Changes to print holdings

Figure 5: Changes to digital holdings

Figure 6: Changes to physical items

Comments about future changes

Change and growth are a constant. As we shift our nonfiction to mainly high-interest topics and reconfigure the layout to face-out shelves this collection is likely to shrink … Fiction is being weeded at present and is also an ever-evolving collection. Hopefully, with a budget in 2022, I will be able to grow our graphic novel collection.

Manga collection will double in 2022 due to student demand. The refresh of the curriculum will influence the purchase of more books for Aotearoa NZ histories as well as Māori voices in English.

It would be nice to have more of a budget so we can cater to more diversities and support better learning outcomes and engagement. We do quite well with the budget we have, but it would be nice to be able to provide for all of our learning communities’ wish lists instead of limiting it to budget constraints.

Table 17: Future changes to collection holdings

Format type | Uncertainty or reduction (%) | Maintenance or growth (%) |

|---|---|---|

Novels, chapter books | 13 | 87 |

Picture books | 20 | 80 |

Non-fiction books | 43 | 57 |

Graphic novels, comics, manga | 6 | 94 |

Magazines | 52 | 48 |

eBook fiction | 56 | 44 |

eBook non-fiction | 58 | 42 |

eAudiobooks | 58 | 42 |

DVDs | 82 | 18 |

Free digital content | 35 | 65 |

Paid digital content | 72 | 28 |

Mobile devices | 63 | 37 |

Artefacts and objects | 82 | 18 |

Maker equipment and tools | 74 | 26 |

Collection development funding

Across all responding schools, the median collection development funding was $11.48 per student, down from $13.97 in 2019.

There is still some variation between school types, although this has reduced with the range now being $8.15 to $12.14 per student. In 2019, the range was $9.77 to $20.50 per student.

The chart below shows changes to median per-student budgets since 2018 for each school type.

Figure 7: Collection development budgets

Table 18: Median per-student funding for collection development by year — break down by school type

School type | 2018 ($ per student) | 2019 ($ per student) | 2021 ($ per student) |

|---|---|---|---|

Contributing | 13.53 | 11.25 | 9.59 |

Full primary | 13.77 | 12.37 | 8.15 |

Intermediate | 7.21 | 9.77 | 10.73 |

Secondary | 15.81 | 15.96 | 9.73 |

Composite | 19.95 | 20.5 | 12.14 |

There is no data for 2020, however, we asked participants to compare their 2021 budget with the previous year. The responses across all school types show that:

the majority of respondents say their 2021 funding was the same as 2020 (63%)

25% say they received less funding for collection development

12% say they received more than in 2020.

Table 19: 2021 collection development budgets compared to 2020

School type | More than 2020 (%) | The same (%) | Less than 2020 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

Contributing | 10 | 68 | 22 |

Full primary | 9 | 63 | 13 |

Intermediate | 16 | 33 | 50 |

Secondary | 6 | 79 | 15 |

Composite | 25 | 75 | n/a |

Some quotes about funding

I feel like the funding we get for collection development is good. I can always manage to get what I need and stay within budget. A lucky position, I know.

Our book-buying budget has dropped over the last 5 years. This is a planned choice not imposed on us. Spending for non-fiction and research resource books is less — partly as online sources are very popular and partly because there is less quality, printed material available.

Even though in theory it would be nice to have a bigger budget, realistically there is a limit to how much time can be allocated to the processing of new resources.

We had had poor funding in past years, and I asked for better funding for this year. I hope this continues next year as the library collection is dated and needs an upgrade. I don't know if I will get the funding next year though the library badly needs it.

My school continues to be very generous with a budget to operate our library to keep titles up to date.

It is difficult to maintain an adequate collection with a continuing reduction in budget.

Impact of COVID-19 on funding

We also asked participants to describe how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted their school library funding.

The majority of responses to this question (165 of 211 comments) indicated that, at the time of the survey, the pandemic had not (or not yet) resulted in a change to their collection development budget. These findings are discussed further under Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Funding sources

Most responding schools receive collection development funding from the school's operational grant. This grant also provides the bulk of their library funding.

For some school libraries, community support (such as fundraising, donations and charitable grants) is an important source of funding.

Table 20: Percentage of responding schools using each funding source

Note that figures add to more than 100% as respondents could choose more than one option.

Funding source | Responding schools using source (%) |

|---|---|

Operations grant | 70 |

Fundraising | 29 |

Other e.g. donations | 24 |

Board of Trustees funding | 21 |

Grants | 10 |

PTA/parent support | 7 |

No collection development funding | 3 |

Themes in comments

We received 68 comments about collection development funding. These are the main points to note from those comments:

21 said their budget was adequate, 19 said it was inadequate.

11 described uncertainty about their current and future funding.

For 15 respondents who commented, it was unclear whether funding was adequate or not.

3 said a lack of time affected their ability to spend the budget and process new resources.

Every year 100% of the funding comes from the operations grant. In 2020, the budget was zeroed. This year $1000 was allocated. When I was given this I attended a board meeting and was granted a further $1700. This funding also came from the operations grant — redirected from other activities. It is very clear that funding will continue to decline.

The funding from the operations budget has decreased in recent years and reliance on the grant money has grown accordingly.

Our PTA organise the book fair and this is the money we have used to buy books over the past couple of years.

I do not automatically get provided with information about the library budget. If I wish to make a purchase, I'll enquire if there is money. Most of the additions to our collection 2018–2020 were from donations.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

The 2021 survey captured the impact of the first 20 months of the pandemic. Responses were collected throughout November 2021 during the COVID-19 Delta outbreak. The Auckland region and parts of the Waikato and Northland were at Alert Level 3 of the COVID-19 Alert System.

We asked about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on 4 aspects of library provision:

library staffing hours

collection development funding

collection holdings

library services.

We received over 200 responses to each of these questions.

Key findings

As expected, library services were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. For the other 3 aspects of school library provision, most respondents reported no change in provision at the time of the survey.

However, there are cross-over effects between the 4 aspects above. For example, some schools spent less time and money buying and processing new materials for the collection because of remote working and supply chain disruptions.

Impact on staffing hours

We asked whether library staffing hours had changed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. We excluded comments that stated only that the library had to close due to lockdown.

The remaining comments showed that library staffing hours generally did not change. Some did report they had lost hours, which were a mixture of paid staffing and volunteer help.

Some respondents said that, although their hours stayed the same, the work they were doing changed. This is discussed further below under Impact on library services.

Some comments

While total paid hours have not been reduced, the amount of hours that the librarian/TA has available for library duties has reduced, and those hours are being deployed predominantly in providing classroom support.

Have been working from home so have had more flexible hours but doing other work, including Zoom sessions with students, so changed role and hours.

Hours have not changed, however, because of the recent Auckland lockdown, I have not been able to do any of the library jobs as have not had access to our catalogue from home (or the books), which means that now that we are back at school, there is lots to be done and not many days to do it.

Yes, hours have been cut and staff not replaced. This has meant programmes and services have been cut in response as we don't have enough staff to cover these.

We lost the international students so, therefore, my hours were cut.

My hours have remained the same but obviously, I have no parent or student help when in lockdowns.

Table 21: Impact of COVID-19 on staffing hours

Change to staffing hours | Number of responses |

|---|---|

No change | 183 |

Paid staff hours decreased | 8 |

Volunteer hours decreased | 5 |

Staff hours increased | 4 |

Impact on collection development funding

Most respondents reported no change to collection development funding because of the pandemic.

Some did lose funding (31 comments), and several gave more detail explaining the change:

10 respondents said they had not been able to access normal sources of funding such as book fairs.

6 respondents said the loss of international fee-paying students affected their funding.

One respondent mentioned a school-wide freeze on purchasing.

Seven respondents reported that their collection development funding increased as a result of the pandemic.

Because the library funding comes from the operating grant it is impossible to tell. However, the school has had to purchase items that in the past we did not — sanitisers, housings for sanitisers, paper towels etc.

Because we have been unable to hold a book fair this year we have missed out on the funds ($400–$500) that it would normally raise for us.

Our budget was cut due to the 2020 pandemic as we lost our international students.

Last year my budget was reduced by 20%, this year it was back to its full capacity.

Surprisingly, despite being told that the school has a limited budget due to no international students, I got a budget increase. Staff were told to trim our budgets, however, I made a strong case to the board/budget group that the library collection desperately needed an overhaul — along with the physical space — and they kindly gave more money to buy books.

Last year we were asked to make cuts to our spending but our full budget has been awarded this year.

Table 22: Impact of COVID-19 on collection development funding

Change to collection development funding | Number of responses |

|---|---|

No change | 165 |

Budget decrease | 14 |

Budget decreased because source of funding unavailable e.g. book fairs | 10 |

Budget decreased because of loss of international students | 6 |

Purchasing freeze in place | 1 |

Unsure, or not known yet | 5 |

Budget increase | 7 |

Impact on collection holdings

Most respondents reported no change to their collection holdings because of the pandemic.

Of those who reported a change in their holdings, the change was generally an increase in the number of digital items held. These included eBooks, eAudiobooks and devices for students to borrow.

Twelve respondents said supply chain disruptions had affected their ability to add items to the collection.

I surveyed students to see if they wanted audiobooks and they said they did but there was little usage.

Number of eBooks on our database has increased to ease access for students, especially Bridget Williams Books.

Was given a free Wheelers 12-week trial, so we had thousands when we had none before. But I have added a lot more free links from other websites.

We have purchased a much larger number of eBooks over the past two years than we would otherwise have done.

Yes, we had no eBooks or audiobooks before lockdown. I did a trial to see how popular it would be and have continued it given the uncertainty of schools returning in Auckland and to help with students' reading over summer, other holidays and during stocktaking time when the library is closed.

It is taking about 6 months to receive physical items from overseas suppliers from some wholesalers. So if we want items sooner, it is costing more. Back orders costs are having to be managed differently when end of financial year comes up.

We have added more free eBook and audiobook options to our collection — or just promoting free options for our students. Brought more escapist reading — fantasy etc.

Lack of material reaching New Zealand has meant I have bought a lot more via Amazon and Book Depository, with collection development money being used to pay shipping, so fewer books into the collections.

Table 23: Impact of COVID-19 on collection holdings

Change in collection holdings | Number of responses |

|---|---|

No change | 159 |

Collection holdings increased — changed or added new collection or format holdings | 24 |

eBook/eResource use increased | 3 |

Supply chain problems impacted ability to add to the collection | 12 |

Collection holdings decreased | 5 |

Impact on library services

We asked how school library services had changed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

28 responses mentioned only the temporary closure of the library due to lockdown (these are not included in the analysis below). Of the remaining comments, most (82) said there had been no changes because of the pandemic.

Flow-on effects of the pandemic

Many of the comments described flow-on effects or consequences of the pandemic on the library or library services.

Once school libraries could open, they had to operate within the COVID-19 protection framework (Alert Level) settings. For example, limiting access to the library to meet physical distancing requirements.

Table 24: Flow-on effects of the pandemic

Effects | Number of comments |

|---|---|

Reduced access due to Alert Level requirements | 23 |

Detrimental effect on reading services or borrowing | 10 |

Some resources removed due to hygiene measures | 6 |

Fewer classes using the library after lockdown | 4 |

Stronger links with local public library | 2 |

Some comments

As the majority of students are not onsite at school we have to promote the library resources available digitally. To make sure both students and teachers have passwords and sign-in instructions for digital resources, the library webpage promotes these resources and outlines what is available.

Have been unable to issue books due to lockdown but encouraging students to borrow eBooks and audiobooks from school platform.

Less contact with students during the pandemic. Books were taken to the classes for reading instead of pupils coming to the library.

Only during lockdown as kids weren't able to access the collection. However, as the libraries closed earlier during our first lockdown, I let the kids borrow more books than usual.

Over the last lockdown, we introduced a click and collect service for students off-site and this was well received. My book clubs have been impacted by reduced and staggered break times.

The library does not seem to be used as frequently as before. I am an observer of library use rather than an actual user. I think the school missed an opportunity to have library resources out in homes being used by whanau in a time of stress and when there was a need for books and reading!

Yes, disruption to events we would normally hold. I do a weekly presentation of new books at our assembly that virtually disappeared.

Supporting teaching and learning, reading and wellbeing

Survey responses showed that schools were proactive, changing their library services to mitigate the pandemic's effects.

Some were able to carry on with management tasks at home, for example, cataloguing books. For others, this work was on hold and catching up put added pressure on their time once they returned to school.

Respondents described supporting reading and learning at home or online by:

promoting and providing access to digital resources

adapting or extending borrowing services for print items

reading to or with students.

Figure 8: Changes to library services because of the pandemic

Table 25: Changes to library services because of the pandemic

Changes to services | Number of comments |

|---|---|

Increased promotion, access, or use, of digital content and platforms | 41 |

Print services — outreach, flexible borrowing limits and loan periods | 25 |

Supporting online learning | 21 |

Enabling access to devices | 4 |

Supporting wellbeing | 4 |

Some comments

As we have been in lockdown for a long time, I have been emailing links on various topics to teachers. I have emailed pictures from books on making costumes for the literacy week which was held online for the first time. I also send links and information on the authors that were supposed to visit and their books, some of which they read online. I have put aside books for teachers to pick up from the library if they can e.g. Bird of the Year books. I have read to students via Zoom. I have responded to various emails from staff regarding items held in the library or that I have recorded to order when possible. I am fortunate to have a web-based software system which I can work on from home. I have prepared various reading lists which I think will be useful and which I will promote to teachers on return to school e.g. empathy, anxiety, perseverance lists. I have also re-classified some areas in the non-fiction area to make the books easier to find. I have also created more shelf labels. I do really miss student contact and have met up with some staff to talk about how they are managing and because I need the contact myself. I have also gone into the library to do some weeding of stock but have primarily been working at home. It is hard being on your own all the time!

Huge impact. The most we have been able to do is remind through school newsletters, class and year level teams about our eBook platform and the EPIC databases that are available for student and staff access. We have created booklet documents by genre for different year levels indicating where they are available as eBooks, e.g. Wheelers platform or the public library. We have had online book club sessions each week and also a writers club. Most of the time apart from this has been spent writing procedures manuals and sorting online documents which don't often have time to do.

Where do I start??? Yes, it has changed! With children at home, we are using digital delivery so much more. In this round of L3, we have organised ‘click and collect’, but we have also really pushed the Wheelers ePlatform. We have created videos to help students with their inquiries. We record regular online teaching sessions where we promote our LMS and also do book sells. We do not run our usual class sessions, but we will attend sessions with classes if teachers request.

Lockdown meant I could not be on-site; could not offer ‘click and collect’ type services. I did more work with specific students helping with Lev 2 English assessments through Zoom calls and once back on site.

Yes, I have been doing regular Zooms with students, talking about new books, reviews, getting visiting Zoom authors, read alouds, quizzes, escape rooms. Also been supporting teachers by moderating Zooms and helping with marking comments.

Yes, I ran an information literacy course on MS Teams about conducting and writing up research including citing and referencing. Also made YouTube vids explaining use of digital resources. Also posted on social media more during lockdowns and ran video book clubs, team meetings etc.

Everything changed because of COVID. I have been promoting events and activities through the Library Web App, attending school Zoom meetings, and more recently, running a ‘click and collect’ library service … but it is not the same :-(

More and more communication with students is happening online. This has been a positive. We are certainly more aware of wellbeing, and I believe that the relationships I have developed with students during lockdown have strengthened as a consequence.

Discussion

The 2021 survey findings show similar issues and continuing trends from previous years.

The major additional findings in this report are about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Variation across schools

2021 survey responses show variation within school libraries continues to be an issue. Differences between school types and sizes are not unexpected. But there is also variation within these, for example:

staffing hours that either enable or constrain library service development and delivery

the perceived level of senior leadership support for school library staff

uptake of professional learning opportunities

collection development funding and its impact on reading and learning.

A key finding from the 2021 survey is that there is less variation in collection development funding across school types. In 2019, average funding ranged from $9.77 to $20.50 per student. In 2021, the range is $8.15 to $12.14 per student.

Employment matters

School library support staff are generally employed under the Support Staff in Schools Collective Agreement (SSSCA). Renegotiation of the SSSCA (which expired on 6 February 2021) is underway. This is a separate process from the ongoing pay equity claim for school library staff.

On 1 April 2022, New Zealand's living wage rose to $23.65/hour. Minimum hourly rates in the SSSCA for Grades A and B, and half of Grade C ($21.78, $21.95 and $23.59 respectively) are now below the living wage.

When our 2019 survey report was published, the lowest hourly rate in the SSSCA was $3.45 above minimum wage. The gap is now $0.58 after the minimum wage rose to $21.20 an hour on 1 April 2022.

Workforce change

School library staff's future work plans continue to show previous trends. In 2021, more than 1 in 5 school library staff are planning to retire in the next few years. And 10% are actively looking for other work outside school libraries. This could mean a turnover of almost a third of school library staff within the short term.

School library collections

The collection trends shown in previous reports continue. Findings from the 2021 survey show that:

print fiction holdings will be steady or grow

print non-fiction and magazine holdings will decline

the inclusion of free digital content will increase

DVD holdings will continue to decline

uncertainty is still highest about holdings of digital resources

few school library collections include artefacts and objects, or maker tools and equipment.

Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

The pandemic caused immediate and major disruptions for schools during lockdown periods. Extra government funding for schools and kura affected by the pandemic helped them:

provide mobile devices and ‘hard pack’ materials to support learning at home

cover relief teacher costs

support students to attend school (including support for wellbeing and cultural wellbeing)

support re-engagement in learning.

We asked about COVID's impact on 4 aspects of library provision:

library staff hours

collection development funding

collection holdings

library services.

As expected, library services were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the other 3 aspects of school library provision, most respondents reported no change at the time of the survey. It is important to note that government-funded operational grants to schools remained the same throughout the pandemic. Most schools pay their library staff and collection costs from this grant and so could continue as normal. Some school libraries rely more on other sources of funding and may have faced hours or budget cuts due to the loss of fee-paying students, for example.

Looking ahead

May 2022 marks 4 years since our first national survey of school libraries. During this period, schools have seen major changes in the education system and the curriculum, with more changes planned. And of course, schools have faced huge disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research could investigate:

the importance of school libraries — and library staff — in supporting literacy, learning and wellbeing

school library spaces, particularly considering shifts towards innovative learning environments in schools

employment matters, especially the impact of pay equity on school library support staff

how school libraries manage uncertainty and adapt to change.

Conclusion and recommendations

It is up to each school and kura to decide the levels of library staffing, funding and other resourcing they need to achieve the goals and aspirations they have for all their learners.

We hope that this report can help guide schools in making those decisions. The findings in the report are best used alongside the other school library development resources and support National Library, SLANZA and LIANZA provide.

We recommend that National Library Services to Schools, LIANZA and SLANZA:

share the findings with stakeholders, especially in the education and library sectors

use the findings to guide the development of our services that support school libraries and school library staff

encourage further research stemming from the findings of this survey

work together to address concerns raised in this report about school library provision

survey schools again to track changes over time and to deepen our understanding of areas identified for particular focus.