Canterbury Communities of Readers Project report

This report highlights findings and insights from the Pūtoi Rito Communities of Readers (COR) Project in Canterbury. This is the final report replacing the interim report published in 2022.

A report commissioned by the National Library of New Zealand as part of its Pūtoi Rito Communities of Readers initiative. Please note, that the views expressed in this report are not necessarily the views of the National Library.

Executive summary

This report highlights the activities and outcomes of Pūtoi Rito Canterbury Communities of Readers, a collective impact project to increase reading for pleasure and the well-being of children and young people in or on the edge of care. Partners included National Library, Kingslea School and regional stakeholders such as Oranga Tamariki and the Ministry of Education.

Reading is a predictor of educational achievement and life outcomes, including for children and tamariki living in communities facing disadvantage and inequality. Between 2020 and 2023 the project provided over 7800 books to children and young people aged 0-18 years, to keep and enjoy. The books were in English, te reo Māori and other languages. A web of people distributed the books, including National Library facilitators, and staff at Kingslea school, Oranga Tamariki, WINZ, Family Homes, Youth Justice facilities, and NGOs.

The evaluation found that the project has been highly successful. Children, young people and their families and whānau are enjoying and reading the books. There is a high uptake of books in te reo Māori and other languages, particularly bilingual books. The books not only affirm the culture and the identity of those receiving them but show children and young people that the organisations giving the books see them, recognise their identity and culture, and are inclusive. The books are being used therapeutically to help support attachment and serve-and-return interactions which are critical to healthy brain development and self-regulation. They are helping children and young people to talk about their feelings, feel less alone and see a hopeful and positive future. They are also providing a welcome distraction during challenging times, such as waits at WINZ offices. The project appears to be having an intergenerational impact, with young parents now reading to their own babies. Interviewees believe the project has seeded communities of readers.

Success factors include the positive way in which the project was framed, so people wanted to coalesce around it. The careful and responsive curation of books was also important. Young people were provided with high-interest, appealing, engaging reading material including books reflecting their languages and cultures. Potentially triggering topics such as violence or sexual violence were avoided. The books were well displayed, and children and young people got to choose the books they wanted themselves. A key success factor was the collaboration, which had the right people at the table, with the National Library providing the project with backbone support and passionate facilitators.

There were a number of challenges. The care, protection and youth justice sector is a challenging and complex sector to work in. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the project.

National Library and the Christchurch Public Library have worked together to ensure the Canterbury COR project, while looking different in this next phase, will be sustained.

Introduction

The purpose of this report is to highlight the activities, outcomes and impact of the Pūtoi Rito Communities of Readers Project undertaken in Canterbury, and to outline plans for the sustainability of the project.

The Pūtoi Rito Communities of Readers (COR) is a collective impact project working with communities across New Zealand to increase reading for pleasure and well-being. The project aims to demonstrate that when communities are connected with the resources and expertise of local and national organisations, these communities can create and sustain better reading outcomes for children and young people. The project, which has incluced six initiatives across New Zealand, has been funded by Te Puna Foundation. Each is undertaken in collaboration with local project partners.

The Canterbury COR project is a partnership between National Library and Kingslea School, working with regional stakeholders including Oranga Tamariki and the Ministry of Education. It is designed to engage children and young people who are in the youth justice system, and those in or on the edge of care, in reading for fun and wellbeing. It also seeks to build and strengthen relationships between young people and their whānau, educators and carers.

The report is based on:

observational field notes

project documentation

along with 33 semi-structured interviews and written feedback from National Library staff (5), Oranga Tamariki (4), Kingslea school (7) and stakeholders who provided books and resources to children and young people (17)

feedback from young people (12) collected by the stakeholders.

While this is final the report as the National Library’s role in providing backbone support will change following the end of this phase of the project, it is noted Canterbury will continue in a different form.

The importance of reading for pleasure

A significant body of research highlights the considerable benefits of reading for enjoyment or pleasure. Reading is an important protective factor and predictor of educational achievement and life outcomes. A multitude of studies show a strong association between reading, reading for pleasure, parental reading, and positive health, wellbeing, and social outcomes in children, including children and tamariki living in communities facing disadvantage and inequality.

Research about the benefits of reading for pleasure

Reading is one of the most important indicators for the future success of a child. Benefits include improved wellbeing, an increased ability to empathise, greater knowledge of other cultures, improved parent-child communications and children’s increased social capital (BOP Consulting, 2015). Parents’ reading to children has been found to enhance early language comprehension and expressive language skills, listening, and speaking skills, and to foster enjoyment of books and reading in later life, as well as grow understanding of narrative and story (Crain-Thoreson and Dale, 1992; Weinberger, 1996, as cited in McCoy and Cole, 2011: 6). Kalb and van Ours (2012) found the relationship between early childhood reading and improved educational attainment to be “a direct causal effect from reading to children at a young age and their future schooling outcomes regardless of parental income, education level or cultural background”. The benefits of reading extend through the childhood years into the teens. Rivers (2006), for example in a summary of the NZ Competent Learners at 14 study, found that teens who enjoy reading are more likely to succeed in school, improve their writing and vocabulary, broaden their imagination and deal with the increasing demands of schoolwork. Moreover, they are more likely to be able to understand complex issues they will have to grapple with, see how others have found solutions to problems and share these. They are less likely to feel alone or the only ones feeling the way they do, and they are more likely to have open communication with adults around them.

There is also considerable evidence to show that reading, including reading aloud to children, is a powerful protective factor. In a study which explored factors that could modify the negative effects of adverse life circumstances such as abuse and neglect, Armfeld et al. (2021) found that one of the greatest predictors of resilience in early primary school students from struggling families was being read to at home. Russell et al. (2022), in their analysis of Growing Up in New Zealand data – a large, nationally representative cohort – found the only potentially modifiable predictor of ‘flourishing’ developmental health status that they could identify was daily parent-infant reading. They supported an approach which took opportunities to promote ‘nurturing care’ strategies to families, including gifting books directly to infants.

The protective power of reading can be explained by neuroscientific research. Children in care, or on the edge of care, often have a background of trauma. Chronic fear and anxiety, commonly experienced by children who live in threatening, chaotic or stressful situations, can make it very hard for them to access their executive abilities – the ability to plan, learn and strategise. This is evident even when those children are not actually present in those high stress environments, for example, when they are at school (Center on the Developing Child, 2010). Persistent and high levels of stress can be toxic to the developing brain and have a strong impact on child outcomes. The Growing Up in New Zealand study, for example, found that children exposed to multiple risk factors have an increased likelihood of experiencing poor health, educational and behavioural outcomes during their preschool years (Woodley, 2017).

However, as researchers from the Center on the Developing Child (2010) found, despite facing severe levels of stress, hardship, and adversity, some children and young people do well, beating the odds. The researchers found that responsive adult relationships based on ‘give and take’ or ‘serve and return’ interactions – where the adult responds to the child and the interactions are individualised to the child’s personality, interests, and capabilities – can protect against toxic levels of stress. These protective ‘serve and return’ interactions are the very parental responses that occur when singing to children, reading to children, telling them stories, or replying to children’s questions (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2004). Moreover, they are the interactions which help to top up the executive function, the domain responsible for planning, strategising, and supporting learning. Neuroscientists have found that reading, and reading to children, can help to reduce the stress response in both adults and children. These have a calming effect (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2004).

Despite the benefits of reading, not all children, families and whānau and communities in New Zealand have the same opportunities to develop a love of reading. A recent report on the Literacy Landscape in Aotearoa New Zealand, for example, shows that nearly half of 15-year-olds never read for fun. There are inequities in access to books, libraries, expertise, support and reading role models.

Literacy Landscape in Aotearoa New Zealand

Bookshelf at Gateway.

The Project

Establishing the project

Based on evidence of the powerful benefits of reading for pleasure, in 2019 the stakeholders met to explore the options for a Communities of Readers project in Canterbury. The aims of this project were to support reading and to provide books to children and young people in the care of Oranga Tamariki. These discussions built on previous collaborations, including National Library providing foundation libraries to several Oranga Tamariki remand homes and youth justice facilities during 2018–2019, continuing into 2020–2023.

In 2020 it was agreed that the initial focus of the project would be in the Canterbury region. Kingslea School offered to provide a hub for the project at Kingslea School’s Arahina ki Ōtautahi campus. The project also covered:

Te Puna Wai ō Tuhinapo (Kingslea School's learning centre in the Youth Justice Facility in Rolleston)

Te Oranga (Kingslea School’s Care and Protection learning facility in Burwood), and

Arahina ki Ōtautahi (Kingslea School’s learning facility in Richmond).

The Canterbury COR commenced with the agreement between National Library and Kingslea School in September 2020.

The vision and mission

The kaupapa of the project was developed by the Stakeholder Group. The vision was to weave a whāriki (a ground-covering mat) of support to inspire a love of reading among tamariki and rangatahi in care, or on the edge of care. Its mission was to work with partners, stakeholders, and support agencies in the Canterbury area to provide books, reading environments and reading-for-pleasure experiences to this group. The stakeholders hoped that providing access to books and providing the conditions supporting children and young people to read for pleasure would help them develop lifelong benefits associated with reading. They wanted to provide books to children and young people in care that would inspire hope and engage them – as one interviewee said, “turning even the most reluctant readers into book lovers”.

Several stakeholders had noted the link between wellbeing and reading, and hoped that with many children, young people and their whānau having a background of trauma, reading, and sharing books and stories would be “calming” and “support attachment.” The role of reading in helping to reduce stress and top up executive function for both children and the adults in their lives was also highlighted.

“We know it can be calming. After the earthquakes there was no power. There were stories of families sitting under the kitchen table reading books to help settle and calm their children.”

“My aspirations for the project were that the children and young people would read and connect with stories that provided windows into good lives, wonderful lives, stories with different pathways, stories of young people overcoming adversity, stories that they could see themselves in and that would inspire hope.”

The interviewees hoped to build a network of support or ‘community’ around the children and young people, as they believed they would be more likely to read for pleasure if they were surrounded by adults who read for pleasure. They envisioned these to be adults “who talk about books, what they are reading, and take an active interest in what the children and young people are reading” and who provide them with “beautiful books on things they are interested in, which entice them to pick them up and have a look.”

“Wouldn’t it be wonderful to see all the adults in their lives support this ambition, with their school, homes, aunts, caregivers, whānau – all the adults in their lives – supporting a love of reading and providing access to books.”

It was hoped that providing access to a choice of appealing books, time to read, inviting quiet spaces where they can sit with a book, and a community of supportive adults would provide “positive flow-on effects of promoting a positive attitude towards books and reading” and spark a lifelong habit with all the associated benefits reading for pleasure unleashes.

“This feels like one of those rare programmes where the link between the desired outcome (more books in high-needs homes/communities) and the method (give them free books) is a blessedly straight line.”

It was acknowledged by stakeholders that for these ambitions, outcomes and impacts to occur, stakeholders would need to collaborate as each stakeholder “understands part of quite a complex landscape and how to actually get the books into the hands of children in care”. Kingslea School, Gateway and Oranga Tamariki social workers, for example, understand ways of reaching children and young people in care and their whānau and caregivers. They also have an understanding of others working with the caregivers and families who might be helpful to connect with. National Library staff, in addition to providing books, expertise and professional development opportunities, would be able to provide the project with backbone support. This includes providing dedicated staff time to support the coordination and management of the project; the selection and stickering of the books; and the distribution of the books to the organisations who can then give them out to children, young people, and their families.

The project undertook to:

co-design and collaborate to shape the project activities, using the expertise of partners and stakeholders

connect with young people in care and on the edge of care and their caregivers, in the places where they already go, and use existing networks and relationships in a multi-agency approach

use the learnings from the project in Canterbury to inform future services and support in other locations

work collaboratively to expand the benefits and impact of the project.

Project scope

There are approximately 600 children and young people supported by five Oranga Tamariki service centres in greater Christchurch. Many of the children are in short-term transit accommodation between difficult family situations and more permanent care situations. About 450 caregivers support these children. The aim of the Canterbury COR was to work with children and young people aged 0 through to 18, depending on the setting.

The books were to be made available to children and young people at school, where they lived, or during their contact with support and educational agencies. National Library planned to provide books for distribution to Kingslea School, Oranga Tamariki social workers, the Gateway Assessment Unit at Christchurch Hospital, Family Care homes, Work and Income offices and through channels that emerged over the course of the project.

Project activities

Distribution of books

Considerable success has been achieved in introducing the books to the children and young people, by distributing books and by putting in place the infrastructure needed to store and display them, such as shelving and display units.

The project provided over 7800 books to children and young people to keep and enjoy; these books were in English, te reo Māori and other home and heart languages, including dual language books. While the initial focus was on children and young people aged 8-18 years, due to the number of younger children the stakeholders worked with, the scope was broadened to include 0–18-year-olds. The project connected with children and young people, providing books through the web of support agencies that operated in the region including:

Te Puna Wai Youth Justice Facility: in the foyer, classrooms and at the prizegiving

Te Oranga Care and Protection Unit (now closed)

Family homes including Highsted, Martindales and Leicester

Child and Family Safety Service (CFSS): to give to young people accessing I2T and Gateway, which provide medical and psychosocial support for some of Canterbury’s most vulnerable young people. The Gateway assessment units are located in Christchurch and on the West Coast

Oranga Tamariki sites including Rangiora, Sydenham, Papanui, Christchurch West, and Christchurch East

Oranga Tamariki psychologists and social workers

MSD sites including Rangiora and Sydenham

Home and Family

The Canterbury District Health Board Mothers and Babies service

A paediatric study site

298 Youth Hub (now called Te Tahi Youth).

Process

The National Library facilitators asked stakeholders about the needs and interests of the children and young people they worked with or who were in their care, including:

languages required

literacy levels

age levels

familiarity with libraries

forms of books, e.g., picture books, hardcover, audiobooks, graphic novels, magazines

genre of books, e.g., non-fiction, adventure, science fiction

types of books to avoid, e.g., dealing with violence and gangs, and

resources needed such as shelving.

Professional Development

A series of professional development workshops was planned. An introduction to the project was held for social workers based at Oranga Tamariki in Rangiora at one of their regular meetings early in the project. Social workers responsible for visiting and monitoring 68 young people in care attended. The social workers were enthusiastic about the project and about giving books to the children and young people they work with. Those interviewed believed that modelling reading to children and talking about the benefits of reading with whānau would help support a reading culture. One said she sits down with the children in her care and caregivers and subtly models how to read with children. The social workers thought families would be unlikely to read pamphlets and suggested the books contain stickers with key messages about the benefits of reading. A professional development session was also undertaken at Kingslea School for teachers and staff on an Accord (Teacher only) Day, aimed at showing how they can be part of spreading a reading-for-pleasure culture.

National Library also ran a session for all of the social workers via Zoom in mid-2022 to talk about the project, reading for pleasure and wellbeing. The session also discussed how picture books and fiction could be used with tamariki and rangatahi. A library of books was offered, which included books for:

caregivers on ways they could support children in their care in relation to access, family, contact etc

caregivers to share with and read with children for enjoyment, and to support difficult situations or conversations, for example covering topics such as trauma, split families, etc. and

social workers to take to caregivers.

Following the session, some of the social workers sent suggestions for books and topics that would be useful for them to be able to share with caregivers. These included covering topics such as feelings, access, attachment, divorce, disability, mental health etc. They also requested books that are “just wonderful life-affirming reads.” In response, the National Library curated a list of approximately 200 books which will be purchased along with bookshelves for Oranga Tamariki to display the books in their offices.

Planned whānau sessions with caregivers were interrupted by COVID-19 lockdowns.

Outcomes and impact

The interviewees reported a wide range of benefits of the Canterbury COR project.

Children, young people, and their families are enjoying the books

It was unclear at the start of the project, whether the children and young people and their families would pick up the books and read them. All the interviewees said the children and young people have enjoyed the books and appreciated being able to keep them.

The momentum grew as organisations heard about the project and wanted their children and young people to benefit from the project. For example, after hearing of it from another office, the Work and Income office at Rangiora asked if they too could have books for the waiting area.

Some interviewees noted that there were “gatekeepers” in their organisations who assumed that children and young people would not be interested in books or reading. Others admitted they were unsure if the books would be read.

“There were low expectations about what young people would or would not be interested in, and assumptions about what young people would want.”

The interviewees were unanimous, however, that the response from children and young people had been enthusiastic, and that many of the young people could not believe they were being given such taonga or treasures for free.

“I have to admit I was a little sceptical as to whether our young people would pick up the books and read them. They have. And they have really enjoyed them. It is about making sure they have a choice of books. The graphic novels have been particularly popular as they make stories that interest our young people so accessible.”

Access to books

Children and young people are getting access to books. It was noted by both Oranga Tamariki social workers and Kingslea staff that children and young people taken into care or living in Youth Justice residences “often have few possessions with them, and books are rarely amongst their belongings.” Moreover, books are expensive and beyond the budget of many families.

“Lots of our young people don’t have much at all, and they certainly don’t have books at home. For those families who might consider buying a book, in tough financial times, books are the first thing to go.”

Moreover, they observed children and young people in care tend to be underserved by libraries. Despite there being a good public library system in Canterbury there are several barriers to using it. Interviewees talked of fines being a deterrent to library use. “Even if they feel comfortable in a library setting, there are other barriers to use such as a fear of having to pay fines for late, lost or damaged books.” Others noted that “these young people often leave a trail of lost books behind them as they are moved from residence to residence”, with resultant library fines restricting further access.

“There is a reluctance to get books out of the library. This is a group of children who move around a lot. It can be hard to keep track of books, which need to be returned.”

It is noted that Christchurch City Council removed charges for overdue books in March 2022 and wiped historical debt, however, fines for lost and damaged books remain. Providing books that children and young people can keep, and removing concerns around loss or damage, were seen as directly addressing some of these barriers to access.

“We obviously have a high-needs cohort and wider whānau, so the more books we can get out and into their homes the better.”

There is a high uptake of books in home and heart languages

Interviewees reported a high uptake of books in te reo Māori and other home and heart languages particularly bilingual language books. They noted that the books not only affirmed the culture and the identify of those receiving them but were highly symbolic as they showed children and young people that the organisation giving the books saw them, recognised their identity and culture, and was inclusive.

“When we put the books out, te reo Māori and other language books of the people coming in tend to get snapped up pretty quickly. What can I say, they are really thrilled to see books in their own language and zero in on them straight away.”

“The (bilingual) books in both English and te reo (Māori) are the most popular. The parents like to be able to share their identity and language with their pepe even if they are not that confident or fluent themselves. There is pride – affirmation – in who they are, and they are able to learn together.”

Stories and books are having an impact on wellbeing

The interviewees are modelling reading to babies and infants with parents and caregivers, and having conversations about the benefits of reading, pointing out how the children are responding, and how the closeness and showing how their voice can calm children down. They say the books are helping to support attachment, serve-and-return interactions which support brain development, and regulation.

“There are so many layers to this project. The content of the books, the language, rhythm, and rhyme calming the brain stem, the neuro-psychological benefits, attachment, the ability to model and coach… it is a holistic way of engaging.”

Some interviewees say they are using the books therapeutically. Some service providers have requested sensory ‘touch and feel’ books as they help the parents they are working with to interact and be present with their children.

“We encourage the parents to interact with their baby, to do it together and put words to it – feel how soft it is.”

Others are requesting books about social skills, feelings, and emotions. These are then read and used to open conversations with young people about how they are feeling and how to regulate their emotions.

“What do you think the character is feeling and thinking? What is the character doing? How could they handle that better?”

For some children, it has become a routine part of their interactions with staff as it is quiet time and enables the children and young people to “settle, calm and connect.”

The books are also used in reunification settings. When the child or parents pick up a book it is an opportunity for them to sit closely together. Although the focus is on the book, the experience is shared.

“Reading a book is side by side. It is something you can do together – share an interest. It is not confrontational. Side by side creates a safe space.”

“Reading to children is active. You are interacting with your child. Watching TV is passive, you are sitting beside them but not interacting. Games can be competitive. Reading a book to your child is a gentle way parents and children who may not have seen each other can reconnect.”

It is helping families and whānau connect

Interviewees said the books are helpful in situations where there is supervised contact, or where the parents have not seen their children for a while. Although many children and young people “run straight to their parent, others are more reticent.” The child can take the book to the parent, or the parent can pick up the book and start reading it “and their child will approach them and sit alongside them.” It is an activity they can share together. “While the focus is on the book, they are able to connect with each other over it.”

It is also an activity that they can do if a parent or baby is in hospital. As one interviewee pointed out, “conversations with babies run out pretty quickly.” It gives them another way to talk to, have fun with and connect with their children.

A welcome distraction

Several interviewees noted that the books provide a welcome distraction during challenging times. Visits to WINZ offices, for example, can be stressful. The security staff encourage parents waiting for an appointment to “pop over and look at the books.” They believe choosing books for their children gives parents something to do and something positive to think about while they wait. “Waiting is hard, you can see they are worried. Looking for books their children would love is a welcome distraction.” Moreover, if they have children with them they can read to them. WINZ staff say they have noticed an improvement in the behaviour of children in the office as they are more likely to sit quietly looking at the books and pictures while waiting for their parent. The staff believe the office feels calmer. “I really think it is helping to reduce the tension in the office.”

Generosity is unleashing generosity

The interviewees believe the generosity of the project is unleashing generosity. People are adding books. At the Work and Income office for example, staff have added beautiful, quality children’s books from home to the collection.

“Staff asked if they could have stickers because we have people donating books.” While there is a risk that this might mean scruffy, low-quality books are included, a champion at the office is ensuring quality control.

In response to the Project, a young person has made her own stickers and is adding her favourite books to one of the libraries at an NGO office.

Several interviewees had wondered if people would “take loads of books leaving none for others” but noted that they had not seen this. Those taking books often spent considerable time looking through the books before choosing one or two to take home.

Intergenerational impact

The project appears to be having an intergenerational impact. Some of the young people in care or youth justice settings are parents themselves. National Library staff were able to provide books for their children. The care and youth justice staff then supported the young parents, talking with them about the benefits of reading, modelling how to read the books and encouraging them to read to their children.

“Many of the young people are parents themselves. We have given them books they can read to their own children. As they were not read to we have shown them how to read to their pēpē. They think it is cool. It is something they can do together.”

Success factors

Approach and framing

Many of the interviewees said the way the project was framed was a critical success factor. It was about generosity and sharing the joy of books and reading.

“National Library were sharing their kaupapa and world with us. Wow.”

It was also about approaching those working on the frontline with children, young people, and their families, respectfully, “treading softly and listening so you are not seen as just another do-gooder trying to change the world.”

“It was not about charity; it was about sharing a love of reading.”

Curated, high-quality books

The books need to be carefully curated

Selecting books for children in care and in youth justice settings poses unique challenges. The collection was carefully curated to avoid potentially triggering topics, such as violence or sexual violence. The facilitators also wanted to provide high-interest, appealing, engaging reading material in the languages and which reflected the culture of those receiving them. This included books in te reo Māori and other home and heart languages.

The stakeholders say feedback from parents and caregivers suggests they prefer books with a story and pictures. They said some find the wordless books “exhausting” as they have to make up their own stories.

“Children with a background of trauma often have behavioural issues. They need consistent and loving interactions that support attachment. When caregivers are tired, at the end of their tether, or just ‘over the day’, they can pick up a book and start reading without having to find the energy to be creative or make things up. In the moment having to make up stories can be overwhelming — a step too far.”

Graphic novels are particularly popular with young people. There needed to be sufficient high-interest/low-reading-level books to capture the attention of readers with lower reading levels.

It is acknowledged by interviewees that books in which young people see themselves and which affirmed their culture and identity are particularly important for children in care. Many of the young people do not have access to their stories and whakapapa, or knowledge of their past, family history, cultural and religious background, all of which help to shape belonging and identity.

The quality of the books matters

The interviewees talked about the symbolism of providing children and young people with high-quality books.

“These are brand new pukapuka. There is no room in the household budgets of our whānau for books.”

“The books are beautiful quality. They are not scruffy old cast-offs from someone else. They are gorgeous. The young people want to take them and read them. They can’t believe they are being given them.”

Providing good quality books is seen as particularly important for this population group as it tells them “you matter, we value you and we want you to have the best, we want you to have beautiful things of value”.

“The quality of the books tells them they are being valued.”

Great care needs to be taken to ensure nearly new books look new. This is time-consuming and labour-intensive.

New books purchased for the project increased the range, choice, and relevance of books available.

“We have been able to augment the offer with books for younger children, graphic novels and books in different languages.”

“If the families went into a bookshop, they would see the same range of books they are being offered.”

The books need to be well-displayed

Care has been taken to ensure the books are well displayed so children and young people can see the range of books they can choose from, and will want to pick them up. Initially the books were stored in boxes which children could fish through. Several interviewees noted the shelves made the books more appealing, enticing and “enhanced their value.”

“For me, the success of the project is that children see the books, want to pick them up, and they are encouraged to do so. That they are so gorgeous they just want to read them. The way the books are displayed nails it.”

It was noted that children and young people often picked up several books that looked interesting to them before deciding on the book they wanted to take.

“The books are visible, tangible and accessible.”

“The bookcases are bright and eye-catching. They are visually appealing.”

A bookcase with a trough at the back enabled the books to be stored and replenished regularly, reducing the frequency of deliveries.

Bookshelf and books in whānau room.

Children and young people are given a choice of books

The importance of giving children and young people a choice of books was identified after it was observed that in some locations, books were being kept in a storeroom and staff were choosing books for the children instead of encouraging the children to choose the books themselves. As a result, browsing bins on wheels and bookshelves that display a range of books on offer were purchased. Professional development sessions reinforced this point.

“Allowing children to pick their own books is empowering — it makes it more likely they'll choose a book they want to read, which will make them want to pick up another book. And that is how the cycle of reading for pleasure starts.”

The books are for the siblings of children and young people in care or youth justice settings

Several interviewees noted that having books for whānau, such as siblings, was important. It helps the children to feel seen and valued, at a time when the focus is on their sibling.

“The books are in waiting rooms. When you are a sibling of someone at the centre of a service, you spend a lot of time in waiting rooms, and at appointments. The young person at the centre is the focus of everything – it is all about them. Siblings can feel invisible and left out. Having books for them, that they can choose, is such a gift as it shows them they are being thought of too.”

Linking reading to pleasure and therapeutic usage

Keep reading enjoyable

The stakeholders interviewed believe reading has to be fun. One interviewee pointed out, “no hard tasks associated with it ever, no expectations, no exceptions”. The focus needs to be on free choice. Children and young people need opportunities, a comfortable place and free time where they can choose to sit down with a book.

“They need a choice over where and when to read, and a place where they can snuggle up with a book.”

Using the books therapeutically

It is noted that many of the books are used therapeutically. Some psychologists and social workers are beginning their sessions with books about feelings, or which resonate with the experiences of the children they are working with. While the therapeutic use may seem contrary to reading just for fun, it is helping to provide mirrors into the experiences of those with a background of trauma.

“I am reading stories of children who have had a tough time and come through it. Or stories that talk about feelings – normalising emotions they recognise but may not be able to name.”

“I am wanting to show stories that show our tamariki that they are not alone, other children have experienced this – and come through it. It is hard but it is possible to build a good life – it is showing not telling them a good life is possible.”

“It is time we can spend together, connecting, establishing a relationship of trust, having fun together – before we get to the hard stuff.”

Reading role models

The adults interviewed have been enthusiastic about the books; displaying them, offering them, talking about them, making recommendations, reading them aloud and discussing them. Children and young people don’t just need access to “a choice of wonderful, appealing books”. The interviewees believe they need positive reading role models, including parents, caregivers, teachers, and other adults in their lives “who can talk about how they read, what they are reading, how they choose books, what they are like” and who can “share their joy of reading with the children and young people and inspire them”.

Adults talking about reading for pleasure have to be authentic.

“These young people are streetwise. They are used to reading people. They will not be convinced if the approach is not genuine.”

Moreover, they need adults to share books with them. While younger children, in particular, are reliant on adults in their lives taking the time to read to them, older children, too, enjoy being read to, particularly those who may not be able to read the books themselves. The landscape is “complicated”. While teachers, staff, social workers, and psychologists say they talked to young people about the books, encouraged them to pick them up, made recommendations and showed “enthusiasm about the young people taking and reading the books” it is unclear to what extent the caregivers and families engaged with the children and young people.

Champions

Having staff who championed the project is really important as there were examples of “books being left in boxes and not distributed or handed out.” The champions help ensure the bookshelves remain topped up, the books are moved around and refreshed, and staff are reminded to encourage families to read, enjoy and take the books home. The champions can also give feedback to National Library staff about the types of books that their families are enjoying. Interestingly, some of the biggest champions for the project are security staff and receptionists, who “love giving out the books to families” and “seeing the impact – it is immediate. You can see it on their faces and in the change in their attitude and demeanour.”

“It enhances my role here for sure – it is something positive and meaningful I can do for people who are often really stressed. And it helps calm things down.”

Collaboration

It takes time to build trust and a shared understanding

Interviewees believe the collaboration is working well. They pointed out, however, that collaborative work, particularly when working with vulnerable population groups, takes time. Initially, there were delays in establishing the project while the implications and potential risks of working with children in or on the edge of care, or in youth justice settings, were considered.

There was also an acknowledgement that it took time for those from different organisations to develop a shared understanding and vision for change. “It is not something which can be rushed.” Several of the interviewees said it was difficult to get their heads around the offer initially as it “felt too good to be true”. “We kept looking for strings (attached).”

The willingness of National Library staff to bring books to events such as the prizegiving at Kingslea Arahina very early on in the project enabled stakeholders to experience what was on offer, and to see the impact the books had on children and young people.

“The National Library staff turned up with books and they were beautiful.”

The right people need to be at the table

In addition to having a shared vision, there needs to be a joint approach in working towards it. This requires the right people at the table as each stakeholder “holds a different part of the puzzle and brings different skills and connections” in a “very complex environment.” The right person “gives us a foot in the door.” There was an acknowledgement that no one could deliver this project on their own.

“While we have been able to provide the books, we were unsure how to get them into the hands of children in care. They are able to tell us how this could work and what we could try.”

The Stakeholder Group includes those who have connections with the community, and who are able to make things happen. Having the school leadership on board, for example, has been identified as a critical success factor. The leadership team of the school is “right behind the project and understands it”.

“This has opened doors with teachers and others who work with the children and young people.”

Similarly, having Oranga Tamariki management involved has been instrumental in helping to facilitate meetings with social workers, who can take the books to caregivers.

Backbone support

In addition to providing books, the National Library has provided backbone support to the project, including project planning, tracking, communications, and providing collateral material. Having dedicated staff has helped to keep the project moving and focused. It was noted that while there are ongoing meetings and communications from the National Library which have helped the project progress, the decision-making is being held “gently” which helped those on the Stakeholder Group maintain ownership of it.

“The right people were leading this project. The cultural side of things was always accommodated.”

Professionalism of the staff

Many of the interviewees commented on the professionalism of the National Library staff. They were extremely responsive to requests for books and were warm and genuinely interested in providing a range of books suitable for the young people the interviewees were working with, creating a “virtuous feedback cycle which continuously improved the books on offer.”

“They understood the young people we are working with and were able to provide such an amazing range and choice of beautiful books. It has been such a special, generous project.”

Kingslea Arahina prizegiving.

Challenges

Challenging and complex environment

Youth justice and care and protection staff work in complex and challenging environments. Interviewees mentioned the necessity of being flexible and adaptable. Meetings and plans can change quickly in response to emergencies. While it had been envisaged, for example, the Stakeholder Group would meet regularly, the nature and pressure of the work, including emergencies on the day, made it challenging to coordinate diaries and get full attendance.

“It is a high stress, complex environment and things can change quickly. We actually arrived on site to undertake staff training, and (an emergency) meant we couldn’t. We had to leave.”

In response National Library adapted their approach where necessary, meeting with organisations separately to keep the work of the project going.

Covid-19 pandemic

The Covid-19 pandemic has been a period of significant disruption. Among the myriad impacts wrought, it affected the Canterbury COR project. Nimble adaptations were required to cope with the lockdowns, meeting and travel restrictions and project timelines. It was envisaged, for example, that caregivers would be reached through regular Support Group meetings, and that they would be provided books and information about the project. These meetings did not happen, mainly because of COVID and post-lockdown interruptions. It was also hoped that the caregivers would talk about books with the young people in their care, to share and reflect on themselves as readers, and develop strategies to build empathy and resilience through books. It is difficult to know exactly if and how frequently these discussions between caregivers and children took place. Sessions with caregivers did not happen as planned and feedback from children, young people and their families was limited to information collected by staff and stakeholders over the duration of the project, rather than by the researcher.

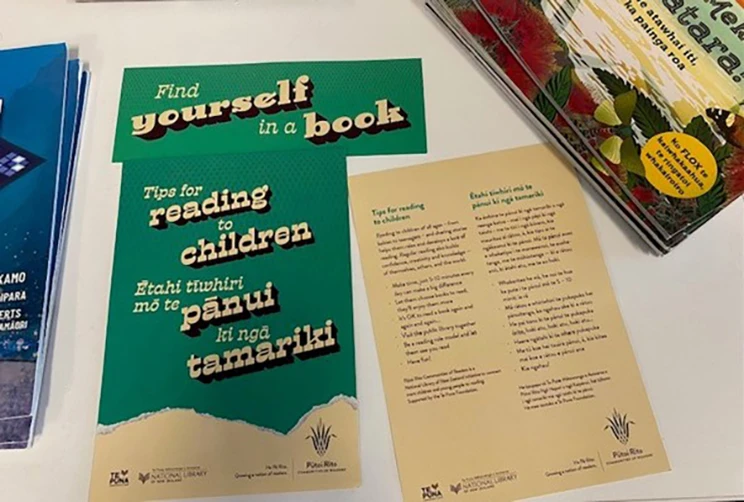

Collateral

The project is not confined to giving away free books. The intent was to provide collateral with clear messaging about the “benefits of reading for pleasure.” It was also intended that the collateral would include messaging to those receiving the books, that they were free and they could keep them or swap them. Parents and caregivers were also to be given tips on how to read to children in a way that engages them.

It took time to develop and distribute the collateral. “It needs to be no longer than six bullet points.” It is also important that the design works and is functional. For example, if books are being upcycled from library collections, the sticker need to be sized to cover any stamps, and the design needs to “pop.” Thought needs to go into the shape and colours.

It was suggested that given the importance of messaging, and the importance of the appeal of the books, that the design of collateral and the messaging where possible has a “local feel” and it is tested to ensure that is understood and compelling to the recipients. It was noted that a sister project, the Dunedin Community of Readers had collateral “beautifully designed, with a local feel which felt like a feature that added appeal to the book.”

Project collateral: Tips for reading to children

Too good to be true

Some of the interviewees noted that there is no such thing as a “free lunch” and wondered if the project, giving away beautiful, free books, was too good to be true. “If something feels too good to be true, it probably is — but it wasn’t.”

Even though the books are free, those in the larger organisations had to convince their managers that the project added value to their work and that it would not take resources away from their organisation. For example, there were concerns as to whether participating in the research would be compulsory and/or onerous.

Communicating and sharing the benefits

Despite the interviewees seeing the therapeutic and calming benefits of the programme, they were unsure if their organisations would consider buying books to continue the programme. For this to happen the outcomes and impacts would need to be communicated and better understood.

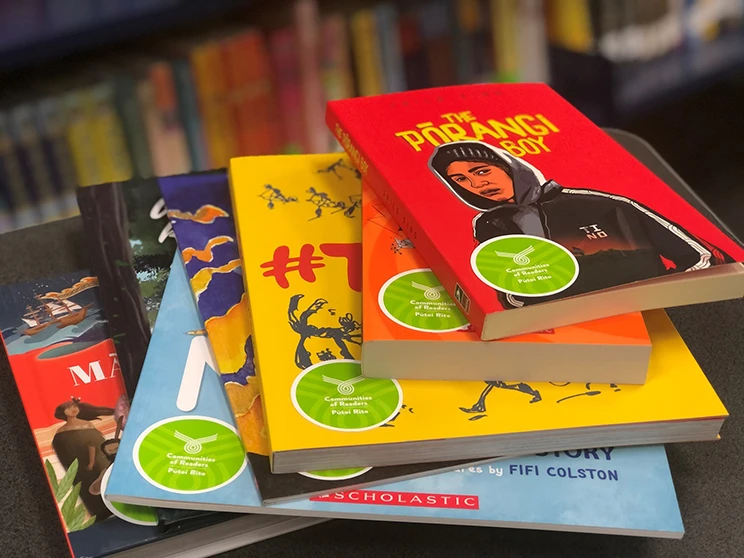

Books stickered and ready to share.

Sustainability

The interviewees wanted to ensure the project is sustained and part of ‘business as usual’. Providing books to children and young people is seen as a great start, but it is hoped that they will have ongoing access to books, at home, in school libraries and through the removal of barriers that currently limit access to public libraries. Several interviewees suggested that nearly new books, weeded from library collections, could be a potential source of books in the future, along with books swapped or shared with others. There was a hope, however, that when considering sustainability, thought would be given on how to keep including access to new books from New Zealand authors, as these support young people to navigate a sense of their identity.

Following discussions in March 2023, the Christchurch City Library and National Library agreed to work together to continue support for the Canterbury Community of Readers initiative. Each organisation will take responsibility for some sites and relationships when this phase of the initiative finishes in June. The Christchurch City Library will undertake the ongoing work and relationships. National Library will support some of the high-needs sites. While the shape of the support will be different, there was general agreement that the next phase would continue to build on the Community of Readers work.

National Library will share Pūtoi Rito collateral (posters, bookmarks, stickers, ‘tips for reading’ brochures) for the Christchurch Public Library to continue to use, or to reuse the messaging in their own collateral. National Library Christchurch will continue to provide books that can be kept by young people and whānau, while the Christchurch City Library will provide books on loan as part of their ‘crate services’. The Christchurch City Library, in recognition of the challenges posed by lending books in care and youth justice settings, anticipate there will be some non-returns and will absorb these. They have also agreed to help distribute some of the ‘keep’ books for the National Library Christchurch.

Research and evaluation

It was also agreed that both the Christchurch City Library and the National Library will share research and feedback about this ongoing work and related reading-for-pleasure projects and look for opportunities to strengthen this involvement.

The interviewees would like to see the research extended to see whether the project makes a difference in the long term.

“I would like to find out in two to three years whether the project has made a difference — if the books hooked them in and sparked a love of reading.”

Lastly, because there is so much evidence that reading for pleasure can make a difference to the well-being, educational and lifelong outcomes of children and young people, the interviewees would like to see the project extend beyond Canterbury. They note as there are fewer than 6,000 children in care across New Zealand, this seems a feasible aim.

Preparing the books for distribution.

Conclusion

The Community of Readers’ vision was to weave a whāriki (a ground-covering mat) of support to inspire a love of reading among tamariki and rangatahi in care, or on the edge of care, by working with partners, stakeholders, and support agencies in the Canterbury area to provide books, reading environments and reading for pleasure experiences.

There are a range of strategies that have been used to increase the likelihood of the children, young people and their whānau picking up and enjoying the books. The books look enticing; they are good quality, new, and beautifully displayed. They have been carefully curated following feedback from stakeholders, so they are well suited to the reading levels and interests of the children and young people. Moreover, the children and young people are given a wide choice they can select from.

Many of the children and young people have a background of trauma. The books are being used therapeutically. Social workers, teachers and psychologists are reading them aloud to calm children and young people before sessions, so they are ready to participate. The books are also being used to help seed discussions on topics such as feelings or empathy.

The interviewees believe the books are also offering hope. They provide windows into what good lives look like, and they also hold a mirror to the lives of those reading them, showing the stories of others who have experienced and overcome trauma and hardship.

While acknowledging that giving children and young people a few books may seem a small intervention, the stakeholders interviewed believe that providing appealing books matched to the interests, language and capabilities of young people is helping inspire the joy of reading. Those interviewed, say many of the young people are talking about and recommending books to each other. It is sparking a virtuous cycle of reading for fun. Interviewees believe the reading role models, environments and support from communities are helping to strengthen young people’s engagement in reading, improve wellbeing and unleash the lifelong benefits associated with reading for pleasure. And this is now occurring intergenerationally. Young parents too, many who were not read to themselves and have low confidence reading aloud, are reading to their babies. They believe the project is seeding a community of readers.

While this phase of the initiative has finished, the Christchurch Public Library and National Library Christchurch are incorporating parts of the project into their ‘business as usual’ to ensure that the children and young people in and on the edge of care, in youth justice settings, along with other vulnerable whānau, will continue to receive the whāriki of support that the Canterbury Community of Readers has “so abundantly provided.”.

References

Armfield, J. M., Ey, L. A., Zufferey, C., Gnanamanickam, E. S., & Segal, L. (2021). Educational strengths and functional resilience at the start of primary school following child maltreatment Child Abuse & Neglect, 122, 105301.

BOP Consulting (2015). Literature review: The impact of reading for pleasure and empowerment. The Reading Agency.

Center on the Developing Child (2010). The Foundations of Lifelong Health Are Built in Early Childhood.

Kalb, J. & van Ours, C. (2014). Reading to young children: A head-start in life?, Economics of Education Review, 40, 1-24.

McCoy, E., Cole, J. (2011). A snapshot of local support for literacy: 2010 survey. National Literacy Trust. London.

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, (2004). Young children develop in an environment of relationships: Working Paper No. 1.

Rivers, J. (2006). Growing independence: Summary of key findings from the Competent Learners at 14 Project. The New Zealand Council of Educational Research.

Russell, J., Grant, C. C., Morton, S., Denny, S., & Paine, S. J. (2022). Prevalence and predictors of developmental health difficulties within New Zealand preschool-aged children: A latent profile analysis. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 1-28.

Woodley, A. (2017). The first 1000 days in the Southern Initiative: Risk, resilience and opportunities for change. A collaboration between Growing Up in New Zealand, The Southern Initiative and the Co-Design Lab. The Southern Initiative.

Alex Woodley,

Point & Associates

June 2023

Download the Canterbury Communities of Readers Project report

Download the Canterbury Communities of Readers Project report (pdf, 2.8 MB)