What makes a good comic?

One thing we comic nerds like to do is to endlessly debate the meaning of the word ‘comic’. We ask ourselves and each other very important questions like 'what is a comic?', 'what are the defining features of a comic?' and 'you and whose army?'. (Other vitally important comics questions include 'do single panel cartoons count as comics?' and 'which is better, Tintin or Asterix?' But these are whole other blog posts.)

What is a comic?

We ask these questions because we are nerds and because comics are a liminal medium. They contain words and pictures; can be short or middle-sized or long; serialised or self-contained or semi-self-contained with recurring characters; they are static and they express time, and they can come in fancy books or tatty magazines or newspapers or be on the web.

These are the factors we discuss, working to persuade each other and the world generally as to which of them are the most important, the most ‘essentially comic’.

I am a comic nerd and therefore I ponder the above. My ideas are quite unfashionable. It’s good that that large chunks of the world want to celebrate long, nuanced, beautifully illustrated, serious, literary ‘graphic novels’ about society’s ills or individual existential crises but I do not share the rapture. Such comics can be impressive but I do not think they best display the qualities of the medium.

To me, these comics with their multiple-frame angles and extensive dialogue are like films, and with their story arcs and character development are like novels. They are comics that kind of, sort of, aren’t really like comics, at least as I know and love them. Comics that are like 'comics' have, in my opinion, a different set of primary qualities. Ones I think are wonderful. The three I’m going to discuss today are text and image interaction, panels, and illogical stillness.

First, I’ll write about these and then I’ll illustrate them with a comic.

Text and image interaction

For me, the interaction of text and image is the most unique and precious aspect of comics. I know there are comics without text and I know these can be lovely but they do not make my brain whirr and heart sing like those with words and pictures entwined.

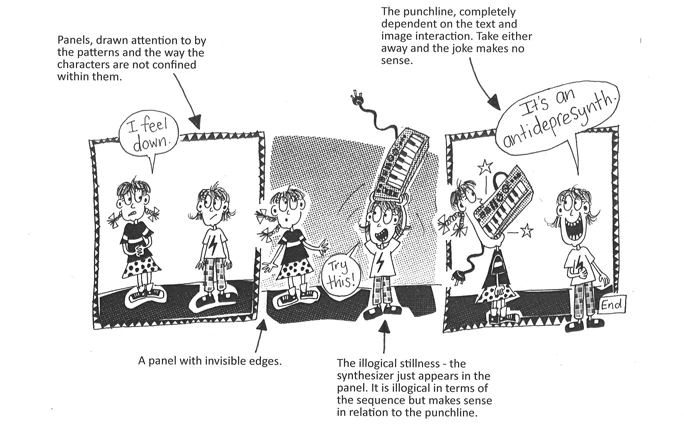

In the best comics, I think you have to have both text and image to make meaning and that if you take either of these away, things should not make sense. This is in contrast to comics where a picture illustrates the text or the text describes the picture (like there’s an image of the sun rising and the accompanying text says something like 'the next morning…') or there are characters doing stuff and chatting (like they are running and one of them says something like 'Slow down! My legs ache'). In these scenarios, you could conceivably take either the picture or the words away and still have something vaguely sensible.

It is the interdependence of words and pictures that allows for a true comics' punchline. Punchlines are another thing I think good comics should have but I do not think they have to be funny. Rather they are a climax, a significant text and image moment that the rest of the comic coalesces around, and they can be brutal and/or sad and/or silly and/or romantic and/or gross instead of, or as well as, funny.

When the punchline is funny, I do, however, think it’s great. This is because laughing feels good but also because it is a reminder of the original meaning of the term ‘comic’. It comes from the Latin ‘comicus’ and means ‘of comedy’. So, originally all comics were intentionally funny (and I say that to be intentionally funny is one of the most serious things there is).

Long comics, although they have significant moments, do not generally have punchlines which is one of the reasons I don’t love them.

Panels

Panels are, I think, unique to comics (with possibly the exception of mathematics textbooks). In most comics, the panels look like frames, a rectangle or square made of lines and surrounding a bunch of related image and text. Sometimes, though, frames are invisible, just a white space where the clump of content ends, and occasionally frames look like something else completely. But whatever their appearance, their function is the same, to segment and organise the comic’s assorted bits.

In many comics, the panels are not drawn attention to. This is generally because the comic-maker reasonably desires for the reader to be enveloped by the story and so the panels exist as a tool for pacing, character development, and action only. In these, it is often considered a real success if the reader doesn’t notice the panels at all.

While I know that using panels in the way just described does require skill, it is not an approach that interests me. I think, instead, that panels are valuable in and of themselves. When I read a comic, the panels are one of the things consistently reminding me that I am reading a comic and that makes me feel lucky and happy. So I really like it then when panels are not just presented as a quiet organising strategy but are pointed out and celebrated as a unique part of the comic-reading experience.

Illogical stillness

One quite influential theory posits ‘sequence’ as the most distinctive characteristic of comics. It proposes that comics are essentially a group of panels, related in some way and that the reader moves through them in a sequence. I have never understood this as a definition. I think lots of things exist as a related group and are in sequence, like shopping lists, mathematical algorithms, and some prose. Take for example the following:

She picked up a pear and then a mandarin and then a plum.

It is text only but the reader has to move through the words in order. To make the comic comparison more explicit, the fruit words are like the panels and the 'and then' is like the spaces between the panels. The sequence mechanism is exactly the same.

For me ‘sequence’ is only interesting when it’s disrupted by illogical stillness.

By this I mean that while panels exist and make meaning as something to be moved through, they also exist individually, are still and self-contained, their own little framed universes. This means you can put things in them that are illogical or without a completely explicit cause-and-effect relationship to the preceding panel. The illogical stillness only makes (paradoxical) sense within a sequence and this makes it a particularly comic kind of thing.

Films cannot do it. Their frames are hampered by the speed of play and the movement of content. Words, I think, are generally too subtle and tied together, and photographs mostly too individual.

It is important to note that the illogicality only exists in relation to panels and sequences. Something that is an illogical panel within the sequence might be completely logical when it comes to a different part of the comic, for example, the punchline.

Here is a comic

OK, so here is a comic that attempts to illustrate all that has been written about. I apologise for using my own work. It’s not because I think it’s all that, it just means there are no copyright issues.

Text and image interaction, panels, and illogical stillness. These are some of the comic features I think are most important, with both my comic nerd head and my comic nerd heart.

Read more

My previous blog post 'Graphic novels' is not comics