Updating the language we use to describe our collections

Read about the work being done by the He Kupu Pāmamae, He Kupu Ora working group to describe our collections using updated and inclusive language that reflects the diversity of our users and the materials we make available.

Reparative description at the Alexander Turnbull Library

Outdated and offensive language haunts archival and library catalogues, potentially causing harm to those searching for and accessing the material these institutions hold. In other cases, there are silences — people can’t find material because the search terms they employ have not been used by the Library in the item's descriptive record. These issues, however, are not beyond fixing.

This blog post outlines some of the issues we at the Alexander Turnbull Library have identified with the words used in the Turnbull Archival Catalogue (Tiaki), our catalogue for unpublished and archival material. It looks at what others in the libraries and archives sector have done, and what we propose to do to address these issues in our catalogues.

The Turnbull Library has long known about potential gaps in its collections, including in this poster from 1975 calling for donations of material related to women. “New Zealand women; the missing half. The answers lie in your hands. In an attempt to preserve women's materials the Alexander Turnbull Library has sponsored the formation of the New Zealand Women's History Research Collection”. [1975]. Ref: Eph-D-WOMEN-1975-01. Alexander Turnbull Library.

What’s the issue?

Libraries and archives are part of the wider political and social context. There is an often unacknowledged power in how we determine what to keep, how we describe it, and how we make that material available. This is not a new idea, and it is a discussion that the archival sector has been having for many years.

Many communities are not well represented in our collections, and some have been described in derogatory, dismissive, or dated ways.

Archives, then, are not passive storehouses of old stuff, but active sites where social power is negotiated, contested, confirmed. The power of archives, records, and archivists should no longer remain naturalized or denied, but opened to vital debate and transparent accountability. 1

At a practical level, the archives and taonga in our collections need a written description. In the past, librarians did this using handwritten card catalogues. Today we use online databases so that researchers anywhere can find the wealth of knowledge that is housed in our collections.

In some parts of the item record, Library staff use free text to describe the item, so the language used may depend on the knowledge and experience of that staff member. In other fields, we use formalised language schemes — called controlled vocabularies — like Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH).

Legacy language

Librarians and archivists use the language of their times when describing collections. Staff may not have knowledge of or connection to, the communities that the material came from. This can lead to language appearing in our catalogues that is inaccurate or has the potential to harm.

It can also often be Euro-centric terminology. This legacy language can be jarring and hurtful for people to read now. Especially since it often relates to key aspects of individual and group identity, like race, indigeneity, gender, sexuality, class, political affiliation, and disability.

We know there are examples of outdated legacy language in our database, and it is something we want to remedy.

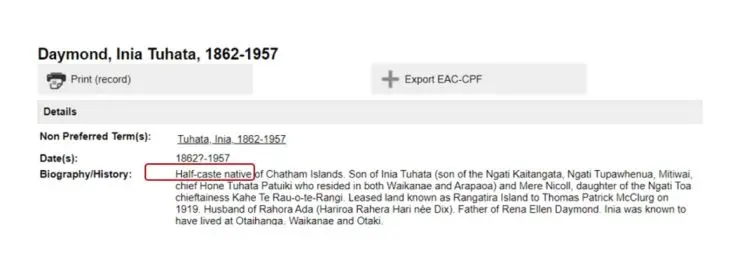

Name record for Inia Tuhata Daymond in Tiaki name thesaurus, from December 2023 (since updated).

Gaps and omissions

In addition to legacy language, there are also gaps and omissions in our use of language. We have a wealth of collections that provide insights into communities, but researchers cannot find them because our descriptions fall short.

For example, this beautiful tīvaevae was originally described as “a handmade large rug of local design”.

Two unidentified local women displaying a tīvaevae in front of trees, Rarotonga, Cook Islands. Whites Aviation Ltd: Photographs. Ref: WA-04357-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Why is this important?

The obvious reason for changing offensive and outdated language is so that people can explore and access our collections without being harmed in the process.

Secondly, the diversity of collections (and our users) should be reflected in our catalogue. Carrying out this work allows us to examine our collections to see what representation of communities already exists but has been buried or described in ways that are incorrect or outright harmful. By improving our descriptions with updated terms and inclusive language, we aim to make records more accessible to all users.

Ultimately, the goal of reparative description is to empower people and communities to feel included and safe when using our collections. Recent academic writing on reparative description from authors like Elspeth Olson backs up this goal, explaining the importance of centring the experiences of people who use the collections. 2

We aim to describe collections in ways that are accurate, avoid harm, make the catalogues more user-friendly, and foster relationships with our users. This is important to us as the Library is always looking to the future, knowing that people from across Aotearoa and the world will continue to make use of our collections in their research projects for decades and centuries to come.

This record was updated during a survey of our objects collection. We took the opportunity to update the title by using single quotation marks to show that the phrase ‘Maori Chief’ came from the creator. We also added the name of the chief to the record in the scope and contents field along with a more complete description of the rich elements of the item using the correct te reo Māori words and macrons. We also added his Iwi and subject headings from Ngā Upoko Tukutuku (Māori subject headings). [Five tin plates depicting Māori portraits and New Zealand scenes]. Published for Iles, Rotorua, by George Hadfield, Wellington, N.Z. [ca 1901-1905]. Ref: Objects-0269. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Honouring the mana of taonga in our collections

It's also important, as both tangata whenua and tangata tiriti/tauiwi, that we honour treaty principles and engage with te ao Māori whenever we can. Reparative description is a step toward this.

In her 2022 doctoral thesis, Karina Lamb writes, ‘Indigenous languages carry descriptions, cultural information and tone that are not possible to present or translate in English.’ 3 This is just one of the reasons why it’s important for us to use the right words and languages in our reparative description process.

Lamb quotes Linda Tuhiwai-Smith, saying:

Indigenous peoples want to tell our own stories, write our own versions, in our own ways, for our own purposes. It is not simply about giving an oral account or a genealogical naming of the land and the events which raged over it, but a very powerful need to give testimony to and restore a spirit, to bring back into existence a world fragmented and dying.

By diving into this reparative description project and finding more accurate descriptions (especially in te reo Māori) we aim to move toward better ways of honouring the mana of taonga in our collections.

Article 13 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) states:

Indigenous peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems and literatures, and to designate and retain their own names for communities, places and persons.

We view this reparative description project as a way of supporting this right and the rights of all communities to engage with the services that the Library provides.

This record was updated during a survey of our objects collection. We took the opportunity to update the title with the correct te reo Māori term and to add the relevant Iwi and subject headings from Ngā Upoko Tukutuku (Māori subject headings). Vosseler, Frederick William, 1878-1959. Pātītī | short-handled axe said to have belonged to Hongi Hika. Ref: Objects-0558. Alexander Turnbull Library.

What have other libraries and archives done?

Internationally, libraries and archives are taking steps to both remedy harmful language in their catalogues and finding aids, and to be more inclusive in how they describe collections. In some cases, this work takes a specific anti-racist or decolonisation focus.

Agencies such as the United States National Archives have put out statements and created guidelines. You will find reparative descriptive work underway in universities such as Harvard and Yale.

The American non-profit resource-sharing organisation OCLC (Online Computer Library Center) convened a community-based group that examined the systemic bias in the infrastructure of libraries and archives with the project Reimagining Descriptive Workflows.

In the United Kingdom, there is ongoing discussion and work by Research Libraries UK and Collections Trust on behalf of museums.

Closer to home, the State Libraries of Queensland's Content Description Principles from 2023 outline its commitment to implementing reparative description and inclusive cataloguing.

At the end of 2023, the National Library of Australia's Guidelines for First Nations collection description by Tui Raven were published by several of the major Australasian institutions in the sector. They give practical advice on reparative descriptions for material created by or are about, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

What are we doing?

We have established the issues we’d like to address, why this work is important, and the other work that’s being done in this area. So what are we planning on doing at the Alexander Turnbull Library?

Our legal mandate, contained in the National Library of New Zealand Act, is to:

Preserve, protect, develop, and make accessible for all the people of New Zealand the collections of that library in perpetuity and in a manner consistent with their status as documentary heritage and taonga...

We believe that problematic legacy language is not respectful of the status of the collections, or reflective of today’s professional ethics. It also means our collections are less discoverable when outdated language is used to describe material.

The Library has put together a small project group, He Kupu Pāmamae, He Kupu Ora, to develop a formal approach to addressing the use of harmful and outdated language in our descriptions for unpublished materials. This group will aim to identify and enrich underrepresented collections that have poor descriptions and to remedy offensive or outdated words used for describing our collections and the people represented in them.

Is this censorship?

Remedy does not mean remove. Recording social use of harmful language is part of our remit to keep Aotearoa’s documentary heritage. Part of the work of this group will be developing ways to protect the research value of such language use without causing further harm.

Importantly, we are not changing anything in the collections — what we’re talking about here is changing how we describe the collections. Some of our descriptive records in the Turnbull Archival Catalogue (Tiaki) will be updated. We might use standard phrasing to indicate a record has been adapted so that you can search that standard phrase to find other such instances.

Language is a socially constructed tool and it does change over time. This means we are able — and arguably we are required — to change our language to meet the current common use.

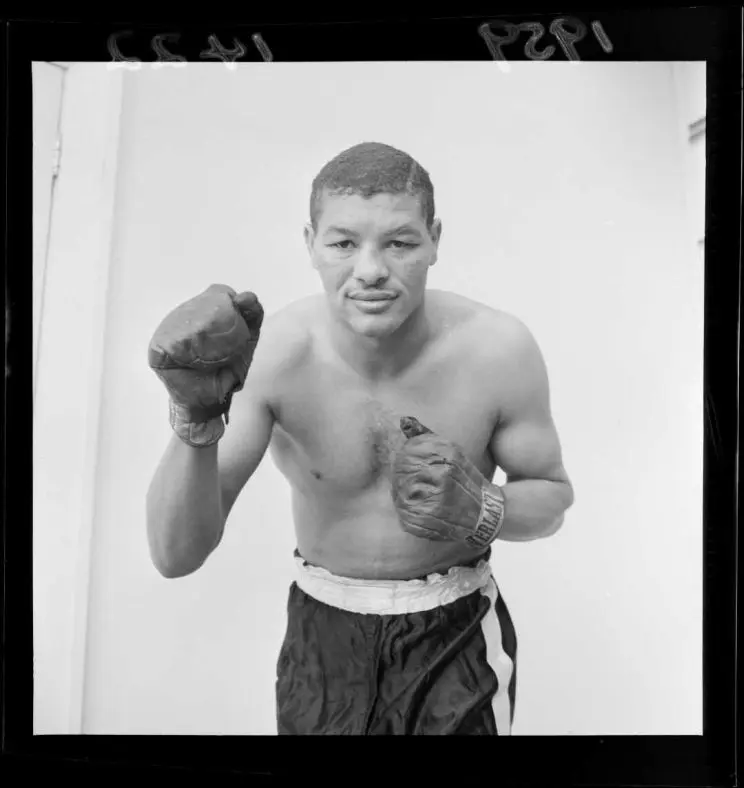

American boxer Willie Vaughn. Evening Post (Newspaper. 1865-2002): Photographic negatives and prints of the Evening Post newspaper. Ref: EP/1959/1422-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

We already use quotation marks to show that particular words come from the creator of the material. You can see that here in our description of this image of boxer Willie Vaughn — Original caption: “American negro Boxer Willie Vaughn”.

We may make deliberate choices not to use creator titles if the creator’s words are outdated. The creator’s words will still be available for researchers to find but might not be the first thing you see when you look at an image of a person.

The word “native” is an interesting case to consider. The example near the top showing the use of it in Inia Daymond’s name record seems a clear case for removal. It is outdated and offensive.

In this case, it’s clear that we should work to improve this record, but other records can be more complex. For example, how might we handle material about the government agency the Native Department? The current agency Te Puni Kōkiri had the word “native” in the official title from 1861 through to 1947.

This is where the working group will provide guidance to staff on how and when to amend language and how to keep a transparent record of changes we make.

In many cases in the past, we have used language that was chosen by the Library rather than the people or communities represented. Reparative description uses appropriate language, often that which is used by communities themselves. Language is fluid and it can be difficult to stay current.

Where possible we will draw on the advice of communities themselves in what language to use. For example, we have used Ngā Upoko Tukutuku (Māori subject headings) for many years in our descriptive work.

And in 2023 we started to use the Homosaurus vocabulary to describe material related to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ+) communities. You can read more about this work in our blog: What’s in a word — describing LGBTQ+ collections.

This is an ongoing project

This work will not be a quick fix. Over the lifetime of the Library, staff have created over 950,000 records that describe our collections. So, the process of updating these records is likely to take time.

We are learning along the way and will probably adapt our approach as we get feedback and discover what works. All while continuing to bring in new material and make that available to you.

We encourage you to reach out to us if you encounter language in any of our content that you feel is harmful or offensive. If you find words in our records for unpublished collections that concern you, let us know by dropping us a line through our Ask a librarian service.

Footnotes

Schwartz, Joan M. and Cook, Terry. Archives, Records, and Power: The Making of Modern Memory. Archival Science 2: 1–19, 2002 accessed 1 December 2023

Olson, Elspeth A. (2023) Mrs. His Name: Reparative Description as a Tool for Cultural Sensitivity and Discoverability, Journal of Western Archives: Vol. 14: Iss. 1, Article 10.

Lamb, Karina. (2022). Objects can speak: Indigenous languages and collections in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. 10.25911/KA1M-V850.

Thank you to my colleagues who have assisted in preparing this blog post, including Jared Davidson, Lindsay Bilodeau, Rata Holtslag, Kimberley Stephenson and Katrina Tamaira, from the working group, He Kupu Pāmamae, He Kupu Ora.

Quotation marks for legacy language used in titles by the creator or previous owner sounds good - but where do you stop? Most of the titles in the title fields of the Drawings Paintings and Prints, and the Ephemera Collections item records are titles used by the creator. Should these titles all go in quotation marks, in case of future judgements?

Thanks for the comment, Barbara. Many of the agencies and guidelines we mention here do recommend using quote marks for creator words and titles. It is also our current practice. This is the kind of issue that the project team will provide some guidance on to staff doing this work. We will also prioritise the extent that we do retrospective changes that you mention.