Tracing your maternal line: Part II — The Durrant family in New Zealand

Using a variety of family history and genealogy resources Research Librarian, Helen Smith, traces her ancestors’ journey from England to New Zealand aboard the ‘Waimea’ in search of greater opportunities and a better life. Part two of a three part series.

Tools used to follow the Durrant family’s journey

Here we will use passenger lists, civil registration, directories, suffrage petitions and electoral rolls to follow the Durrant family’s journey from England to New Zealand.

Having no letters, diaries or other written records left by this family, we can use church and friendly society records, obituaries and newspapers to find out what was important to this family and what might have motivated them to support women’s suffrage in the early 1890s.

The Durrant family immigrate to New Zealand

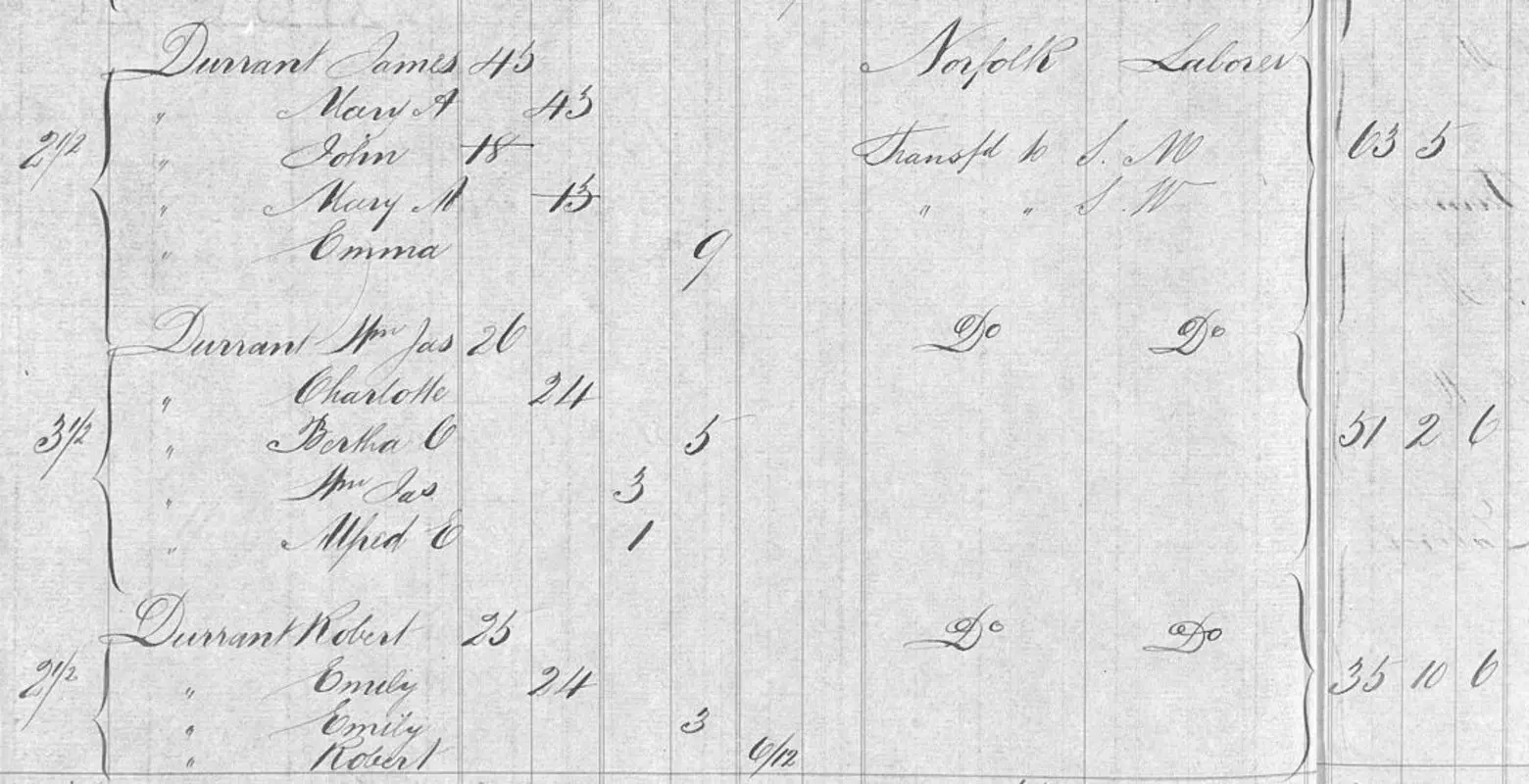

Disenchanted with London life, three generations of the Durrant family applied for a free passage to New Zealand and were selected by the Emigrants and Colonists’ Aid Corporation as suitable settlers for the Feilding Settlement. Settlers were required to be 45 years old or younger. James and Mary Ann, 53 and 48 years respectively, gave their ages as 45 and 43 to qualify.

Escaping the unsanitary living conditions of Canning Town, five-year-old Bertha and her brothers, William James (known as Will, 3) and Alfred (1), together with their parents and paternal grandparents, sailed away from England on 2 July 1876 on the Waimea.

Also on board were William James’s brothers Robert and John, and their sisters Mary Ann and Emma, together with Robert’s wife and their two young children. They arrived in Wellington on 4 October 1876.

The Waimea passing Pencarrow Head as it enters Wellington Harbour. Pen and wash sketch by New Zealand artist Alfred Memelink. Copyright Alfred Memelink, used with permission.

The Evening Post gave this account of the voyage:

The New Zealand Shipping Company's ship Waimea arrived in harbor shortly after noon to-day, 93 days from London. She is one of the cleanest immigrant ships that ever come into Wellington. […] Left London on the 2nd July, cleared the Channel on the 8th, and had moderate winds until the N.E. trades were taken. In 10 deg. north the N.E. trades were lost, then moderate variable winds until crossing the Equator, in 27-20 west. The S.E. trades were moderate, and lost them in 26-50 south and 30 west, and from thence to the Cape of Good Hope moderate winds. The easting was run down in 46-47 south, where she encountered two heavy gales, and thence to sighting Cape Farewell on last Saturday moderate winds were experienced, and with S.W. winds came through the Strait, arriving off the heads yesterday evening.

Three deaths of children under two years of age, and one birth, occurred during the voyage. No accident or sickness is reported. […]

The Waimea has on board 290 immigrants, equal to 240 statute adults. Of these 70 1/2 are nominated and 57 1/2 selected by the Immigrants and Colonist Aid Corporation, and intended for the Fielding settlement. The male immigrants are classified as follows: — 70 farm laborers, 4 shepherds, 1 coachman, 9 carpenters, 100 of miscellaneous occupations. Among the list of single women are 25 general servants. Their different nationalities are — English, 181; Scotch, 17; Irish, 81; Welsh, 8; Channel Isles, 3.

William James’s brother James arrived in Hawkes Bay later the same month on the Inverness with his wife Sarah and son James, and their baby, born on the voyage, whom they named George Inverness.

The Durrant family listed on the manifest for the Waimea, Archives New Zealand Passenger lists, IM-15-14-267, Waimea (Ship), 2 Jul-4 Oct 1876, on Family Search. With permission of Archives New Zealand.

The Feilding Settlement

The Durrants were among the more than 1,000 immigrants helped by the Emigrant and Colonists’ Aid Corporation to settle in the Feilding Settlement around Halcombe in the mid-1870s.

William James’s obituary informs us that William James and Charlotte briefly lived in Halcombe and Feilding before settling in Wellington.

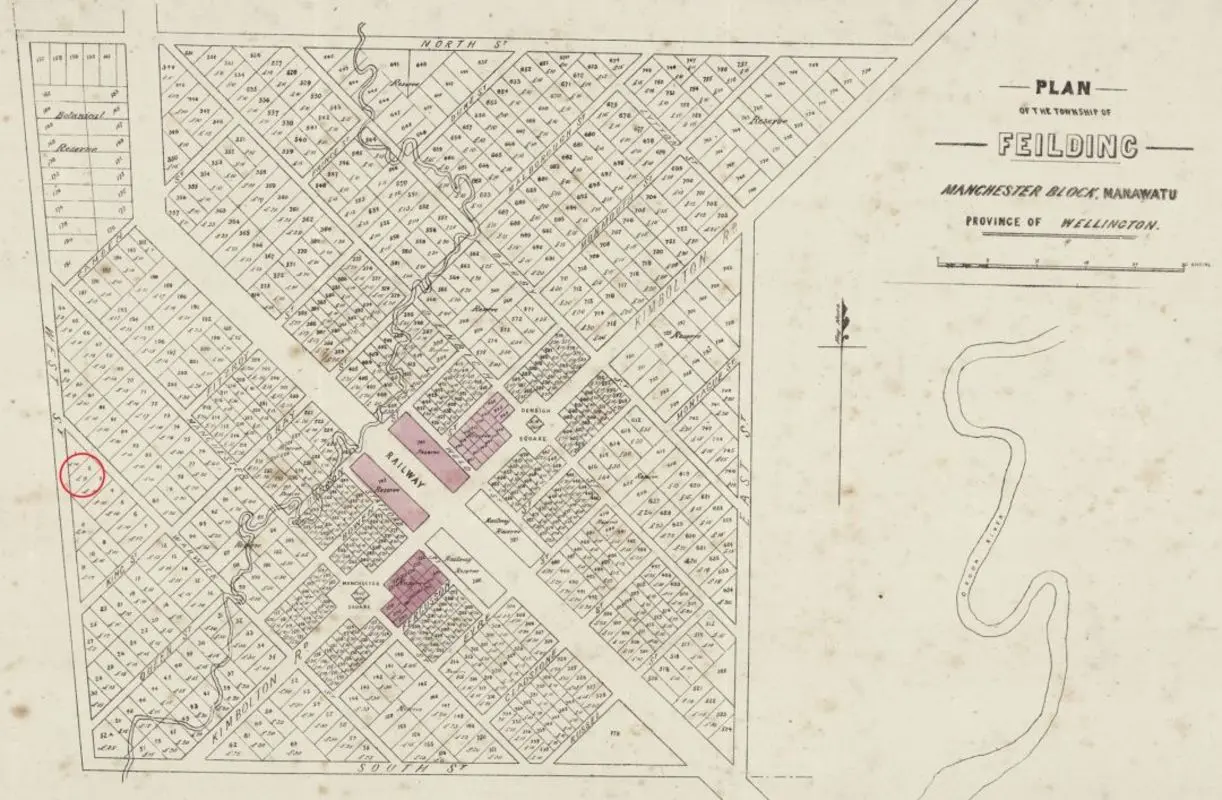

The Manawatū Electoral Roll dated 31 August 1877, 1 May 1880 and 10 October 1881 confirms that William James had freehold property in Feilding (section 2). His father James had freehold property in Halcombe: section 656 on the 1877 and 1880 rolls and section 256 in 1881 and 1885.

Plan of the township of Feilding: Manchester Block, Manawatu, 1870s, showing section 2, William James’ property (circled red). Looking at a modern map it is possible to see that this section is currently 75A West Street and 136 Warwick Street. Ref: 81268192800002836. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Plan of the township of Feilding: Manchester Block, Manawatu, 1870s, showing section 2, William James’ property (circled red). Looking at a modern map it is possible to see that this section is currently 75A West Street and 136 Warwick Street. Ref: 81268192800002836. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Death comes to Te Aro

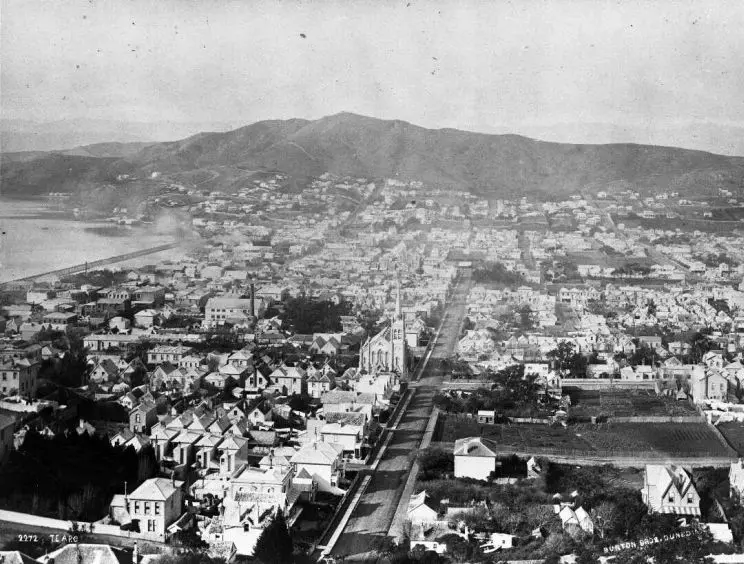

In May 1878, now living in Taranaki Street in Te Aro, Wellington, Charlotte named her first New Zealand-born baby Albert Allen Durrant, after her mother, Mary Allen. William James had gained work with the Wellington Gas Company, in Courtenay Place, as an engine driver, the same occupation he had in Canning Town.

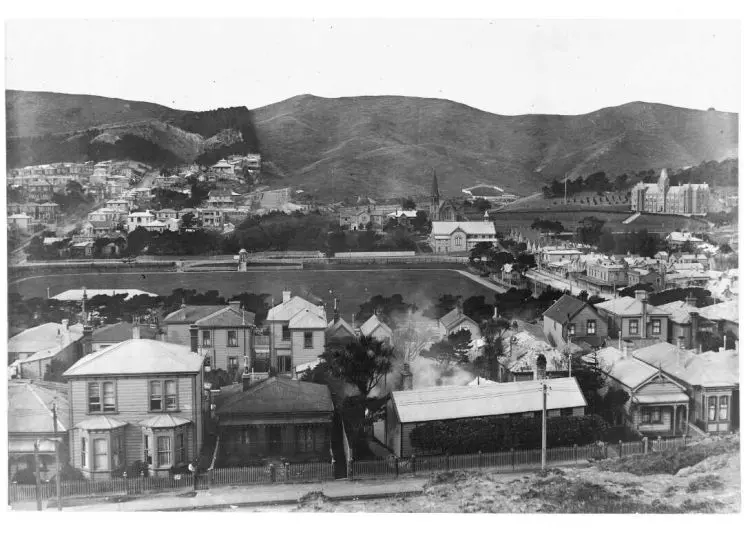

Photograph of Te Aro, Wellington, taken by the Burton Brothers, ca. 1880. Taranaki St, where William James and Charlotte lived 1878-1889, runs across the picture and sits at the end of Ghuznee St, the wide street in the centre of this photograph. Smoke rises from the gas works on the waterfront, where William James worked ca. 1878-1883. Ref: 1/2-018791-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

In December 1878, baby Albert became unwell and when Dr Harding saw him, on the 17th, he was diagnosed with influenza and bronchitis. Two days after the doctor visited, without the benefit of modern medicine, little Albert died. Only a month later, on 24 January 1879, his brother, three-year-old Alfred, also died. Alfred’s death registration states that he died of worms and pleurisy. The two boys were buried in Sydney Street Cemetery in Thorndon.

Diseases like typhoid, diphtheria, scarlet fever, measles and cholera were spreading rapidly in crowded Te Aro at this time because of inadequate sewerage and drainage systems. Typhoid can have similar symptoms to influenza and pneumonia and young children were sometimes misdiagnosed: this may have been the true cause of their deaths.

After another outbreak of typhoid in 1892 in the same area, it was discovered that trapped sewer vapours were making their way back into people’s houses after heavy rain. Typhoid had been a recurring problem in the area for years.

Te Ara, The Encyclopedia of New Zealand has a typhoid map that shows Taranaki Street, where the Durrants lived in 1878-79, during this later outbreak.

The Durrant family go to Australia

In about 1881, William James’s brother Robert Durrant, who had settled briefly in Napier, made a permanent move to Melbourne, Australia, with his young family.

A little while later, William James, Charlotte, and their children, together with William James’ mother Mary Ann and sisters Mary Ann and Emma, followed them and stayed in Melbourne for a time.

Eventually, the family decided to return to New Zealand and their return voyage on the Wairarapa in July 1883 can be viewed on Public Record Office Victoria’s Outwards Passenger Lists 1852-1923.

Once back in Wellington, William James was employed as a blacksmith with the successful company Thomas Ballinger & Co, which manufactured a wide range of plumbing and roofing supplies, where he remained until ill health forced him to retire in 1912, after nearly 30 years with the company.

The family grows

School registers show that Bertha started at Buckle Street Girls School in September 1879, aged 8 years. Her brother Will attended Mount Cook Infants’ School (New Zealand’s first kindergarten) and then went to Taranaki Street Boys’ School.

The school registers record that they both went to school while they were in Melbourne and returned to their former schools at the end of July 1883.

It would be almost a decade after the deaths of Albert and Alfred before more children were added to the Durrant family, with the birth of Bertram Jesse on 9 August 1888 and the adoption of Evelyn May Garner, daughter of Sarah Garner, by Charlotte in March 1895.

Photograph of Charlotte with baby May, ca. 1893. Taken from a small laser print given to the author’s mother by her newly discovered cousin Pam Pentecost née Durrant, ca 2003. Digitally restored by Camera House, Lower Hutt, in 2023. Image supplied by the author.

The Church of Christ

Charlotte’s obituary, published in the Evening Post on 31 May 1939, states that ‘Mrs. Durrant was one of the first members of the Church of Christ at Wellington, and took a great interest in all activities connected with the church for the past sixty years.’

The Alexander Turnbull Library holds some records of the Wellington South Church of Christ and these confirm that William James and Charlotte, and William James’s parents, James and Mary Ann, were early members of the Church of Christ on Dixon Street. These four are listed as among those of the Dixon Street congregation who began meeting for worship in Newtown in 1892 and who officially transferred their names from the Dixon Street roll to the new Wellington South (Newtown) congregation in 1894.

The Australasian Christian Standard of July 1892 reported that ‘the south end of Wellington has long felt the need of a church, and a morning meeting has been started in the State schoolhouse. It will prosper, for some of our best Christians live in Newtown’.

In 1906, when a new Church of Christ was opened in Kilbirnie, the Durrants went there. It was recorded at a Wellington South church meeting in December that year that ‘Mrs Durrant would finish her work as cleaner of the chapel on Saturday week’, a job she was paid for.

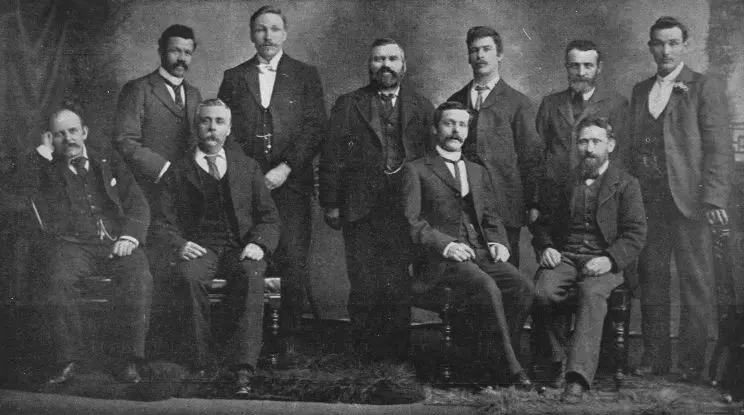

Photograph of William James (on right in the front row) with a group of Wellington South Church of Christ Sunday School workers from Jubilee pictorial history of Churches of Christ in Australasia, 1903. Ref: P q289.9 MAS 1903. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Another obituary for Charlotte, published in the New Zealand Christian on 11 June 1939, reads:

Durrant. — The death of Sister Durrant, Snr., on May 25th, removes another of the few remaining members who, in 1892, brought the Wellington South Church into being. In the year 1880, in the old Te Aro Baths, she was baptised into Christ by A. B. Maston, the first preacher of the Churches of Christ in Wellington. At that time, the Church was meeting in a public hall and A. B. Maston was drawing crowded audiences.

When the Dixon Street Church was built, she and her husband and other members of the Church who lived in Kilbirnie, were in the habit of walking along the track over Mount Victoria three times each Sunday to the different services.

With others, she assisted in the formation of the Wellington South Church, and during her long life, she and her husband were faithful and consistent members of the Church. For many years her husband was choir master both at Dixon Street and at Wellington South.

She was one of the pioneers to whom New Zealand owes so much, and carried the bricks and helped her husband to build their first home, and knew what it was to bring up a family in times of great hardship and poverty without any Government assistance.

William James Durrant and music

William James’s obituary states that he was ‘well known in musical circles’ and served as the first Church of Christ’s choirmaster for 30 years. Whether his parents were musical, or he learned to read music through the church, is unknown. The singing of hymns was an integral part of worship in both the Methodist Church and the Church of Christ, something that would have been alluring to a musical person like William James.

The New Zealand Times reported that William James conducted ‘a strong choir’ at the Opera House and various other venues in 1892, supporting an evangelist preacher. Newspaper reports show that William James led the Dixon St church choir, and performed solos and duets, at church gatherings in 1893. In January 1894, the Church of Christ minutes record that William James was to lead a singing class one night a week.

When the Wellington South Church of Christ’s new church opened in 1899, the Evening Post reported that ‘A well-trained choir under Mr W J Durrant contributed special singing at the various services’.

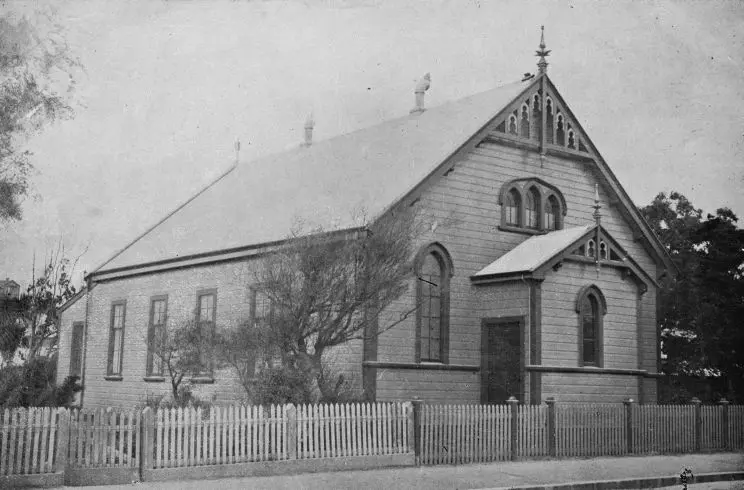

Photograph of the Wellington South Church of Christ from Jubilee pictorial history of Churches of Christ in Australasia, edited by A.B. Maston, 1903. P q289.9 MAS 1903. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Music in support of temperance

Proponents of the temperance movement, concerned about the damage that alcohol caused to families and society, advocated moderation or abstinence from alcohol. Protestant churches, including the Church of Christ, were supportive of the temperance movement.

Newspaper articles from the early 1890s show that William James actively supported the movement. When, in October 1890, the Bible Christian Denomination gathered in the Rechabite Hall in Manners Street, Wellington, the Evening Post recorded that ‘Mr. Durrant conducted, and members of the Blue Ribbon orchestra and choir assisted, the singers of the Bible Christian congregation also joining in the service’.

In February and May 1891 William James conducted the Gospel Temperance Choir, which sang a service of song called The River Singers, in aid of the Gospel Temperance Mission, to a large and appreciative audience. The piece was noted as being ‘descriptive of the social grimness, the haggard suffering, and, at the same time, the religious possibilities of the life of the very poor in a city like London’, something that the Durrant family might have been able to relate to their years in Canning Town.

Charlotte and William James Durrant, ca 1905-1915. Digitally restored by Camera House, Lower Hutt, in 2023. Image supplied by the author.

Involvement with the John Knox Lodge

William James’s obituary, published 5 September 1919 in the Dominion, states that he was one of the founders of the John Knox Lodge No 50 of the Protestant Alliance Friendly Society of Australasia (PAFSA). The Library holds some records of the John Knox Lodge. Looking at the membership registers, I found that William James became a member on 30 May 1879, the date the Society was inaugurated, and Charlotte joined on 19 August the same year.

The membership books provide information about the individuals, such as their occupation, birthplace, age, religious denomination, birth and death date and, in Charlotte’s case, her cause of death. The Durrants are recorded as being Primitive Methodist and it is noted that they had left when they went to Australia and rejoined on 27 November 1883.

The minute books record that William James and his son, Bertram Jesse, served as officers for several years. Members paid regular dues to belong, and, in return, the Lodge gave financial relief to members in times of need, such as the payment of funeral costs.

William James and Charlotte’s elder son, William James, belonged to the Loyal Britannia Lodge of the Manchester Unity Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF). The officers of the PAFSA had similar titles to the Odd Fellows and their rituals and ceremonies, which included secret signs, handshakes and passwords, were alike. The primary aim of the PAFSA, however, was to protect Protestant values.

The John Knox Lodge and temperance

The Protestant Alliance Friendly Society of Australasia’s High Court Degree Manual lists its ‘three great principles’ as Relief ‘from suffering, distress, poverty, and other evils’; Fidelity ‘faithfulness, loyalty, adherence to right, honesty and truth’; and Truth ‘speak and practice truth, though it clash with men’s tastes, their practices and prejudices’. Temperance was strongly encouraged:

The practice of which will not only guard the soul against those insidious allurements by which its nobler feelings are too often corrupted but form the mind to a general habit of restraint over our appetites, our passions and our virtues, any of which if allowed to acquire an excessive influence over us must unfit us for everyday life. Temperance, then, if allowed to have its influence on us, will prove to be the crown of all virtues; it will modulate our lives and make us nearer like Christ, whose life was one sweet harmony.

Temperance and suffrage

We have seen that the Durrant family were involved with groups that advocated temperance. Another organisation, the New Zealand Women's Christian Temperance Union, strongly believed that, if women had the vote, more could be done to improve the lives of women and children.

They saw women and children suffering because their husbands and fathers drank away their wages or became violent, and that abused women had little recourse to justice through law. They also saw that men, however flawed and debased, could vote but intelligent, respectable women could not.

Using electoral rolls and suffrage petitions for family history research

In early colonial New Zealand women were unable to vote, hold office, or play any part in politics. We can use the New Zealand Electoral Rolls to trace male British subjects who owned property, and were at least 21, from 1853. We can trace Māori on the rolls from 1867 (without the property ownership requirement) and most men can be found there from 1879. While we can use electoral rolls to see where a woman’s husband or father lived, for most of the 19th century we cannot find women themselves on New Zealand electoral rolls.

Fortunately for women, and us as researchers, the New Zealand Women's Christian Temperance Union took petitions to Parliament in 1891, 1892 and 1893 asking that women be allowed to vote. More than 9,000 signatures supporting women’s suffrage were gathered in 1891 but, sadly, this petition has not survived.

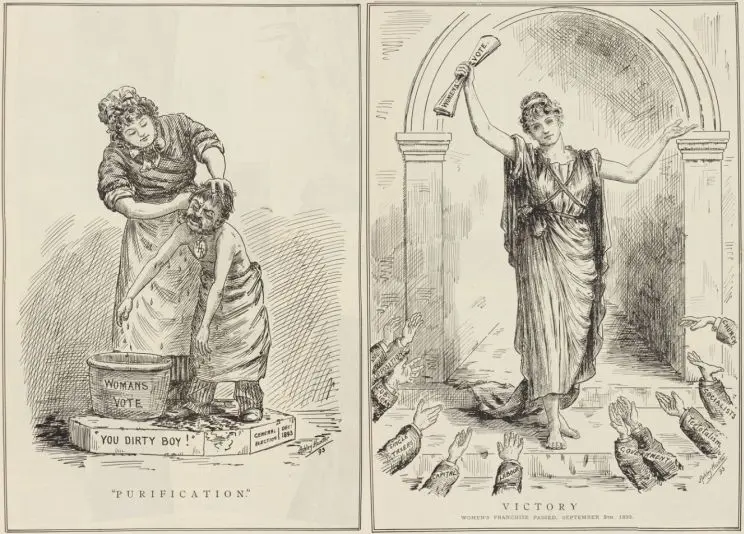

Cartoons published in the New Zealand Graphic, 18 Nov and 16 Sept 1893. Purification NZG-18931118-0417-01 and Victory NZG-18930916-0201-01. Auckland Libraries Heritage Collections.

The Durrant women sign the 1892 suffrage petition

The 1892 campaign yielded over 1,900 signatures in six petitions. A transcript of most of these names can be accessed on the New Zealand History website. (About the suffrage petition - Women and the vote | NZHistory, New Zealand history online) Charlotte Durrant can be found here as ‘Mrs W Durrant’, together with her sisters-in-law, ‘S Durrant’ (Sarah, wife of James Durrant), ‘Mrs John Durrant’ (Alice) and Emma Twoomey (nee Durrant). These three do not appear on the 1893 suffrage petition, so it is good to find them here. It tells me something about how these women thought: that they believed that change was possible and that women should have more say in their futures.

The 1893 suffrage petition

The movement picked up in 1893 when thirteen petitions circulated, gathering the names and addresses of almost 32,000 signatures of adult women throughout New Zealand. Only nine of these women have been identified as Māori, and one as Chinese, and the list also includes a few European men. The twelve smaller petitions have not survived and there are also some 1,500 names missing from the larger petition. You can search a database of almost 24,000 names and addresses, created from a transcript made by volunteers from the New Zealand Society of Genealogists, on the New Zealand History website.

While the Durrant women are not listed on the petition which was submitted to parliament on 28 July 1893, Sarah Garner is. She gave her address as ‘Sussex Square’, the same street her daughter Evelyn May was born in on 5 May that year. In 1896 Sarah Garner, her daughter now adopted by Charlotte, is listed as a spinster, living on Dixon Street. She would marry Peter Nicholson the following year.

Using electoral rolls and directories to trace the Durrants

Although William James appears on the Manawatū Electoral Roll as late as 1881, we know that William James and Charlotte were in Taranaki Street in 1878, when baby Albert died. William James is also recorded in Taranaki Street in the Wises’ Directory of 1880, 1883 and 1887 and the electoral roll dated 25 March 1887.

William James is on the electoral rolls at Belfast St, off Sussex Square, in 1890, 1893 and 1896 and the Wises’ Directory of 1891. The Stones Directory lists him as a blacksmith in Sussex Square from 1892 to 1895 and the Wises’ Directory has him in Sussex Square in 1894 but also in Gordon St, Newtown, in 1892.

Charlotte’s appearance on the Wellington Supplementary Roll dated 7 November 1893 in Sussex Square is useful, as are the rapid changes of address in the directories: when people appear on rolls for the first time, are on supplementary rolls, or change address, we can be more confident that the records are accurate. The marriage registration of 17-year-old Bertha to Bertram Walter Bird of Thompson St, ‘at the residence of the bride’s parents, Constable St, Newtown’, in November 1888, however, warns us that the directories and electoral rolls do not give a complete picture.

The Wises’ Directory of 1894 lists William James in Sussex Square ‘on right-hand side from Buckle St’ and nine houses down from Dock St, placing it in the centre of the second row from the front in this photograph, taken ca. 1900. Ref: 1/2-059705-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

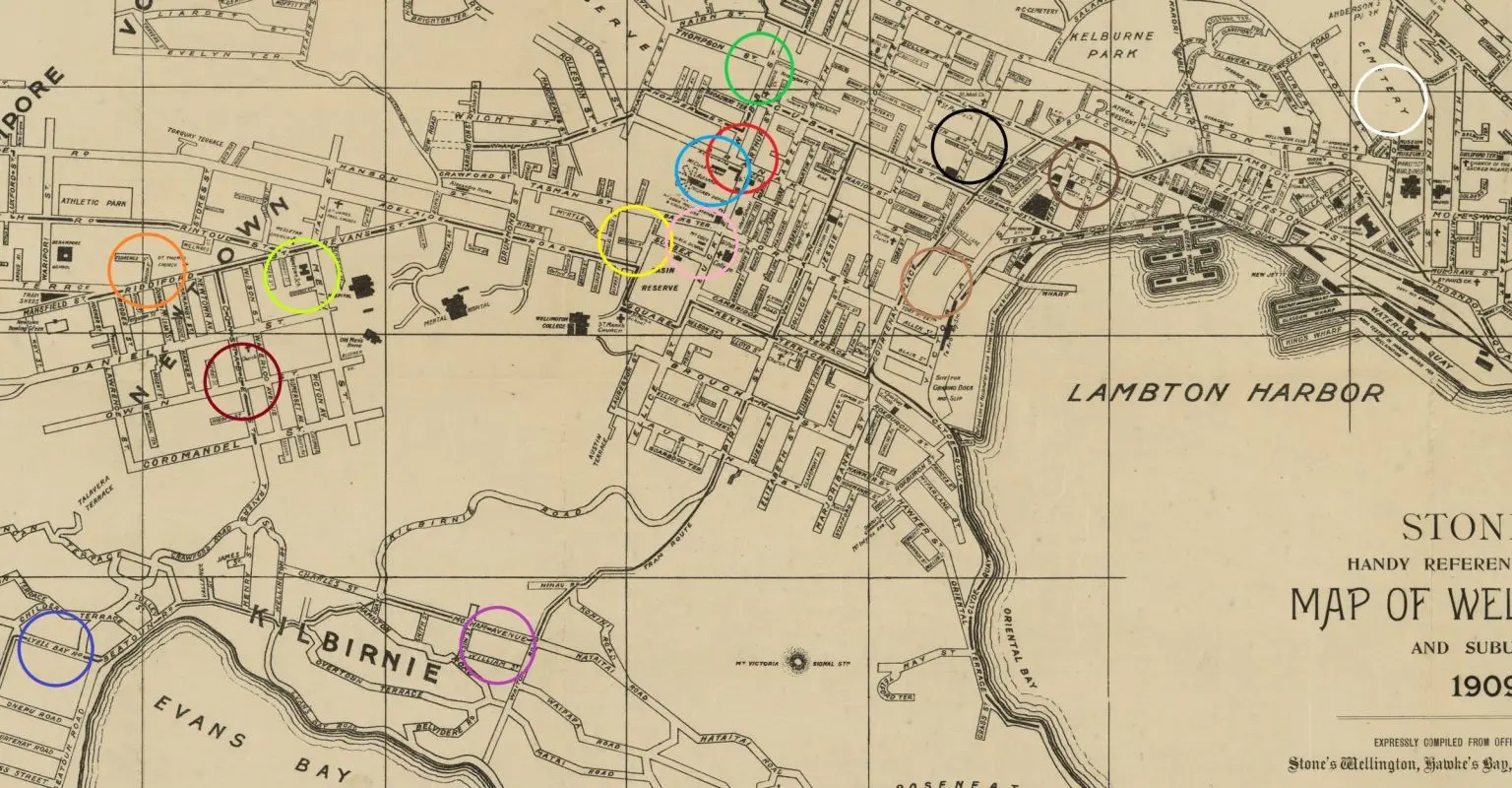

It appears that, from about 1887, the family moved a few times between Newtown and the Sussex Square area, before the 24 Nov 1896 Wellington Suburbs Supplementary Electoral Roll confirms that William James and Charlotte had moved, with children Bertram and Evelyn May, to their last house at 33 William Street, Kilbirnie.

Detail of a map of Wellington showing where William James and Charlotte lived in Taranaki St, ca 1878-1887 (red); Constable Street, 1888 (dark red); Belfast St and Sussex Square, ca 1890-1895 (yellow); Gordon St, 1892 (orange); William St, ca 1896-1933 (purple). Thompson St, where Bertha and Bertram Bird lived before they married in 1888 (green). Also Wellington Gas Company, where William James worked ca 1878-1883 (light brown) and Ballinger’s, where he worked 1883-1912 (dark brown); Church of Christ Dixon St (black), Wellington South (lime) and Kilbirnie (dark blue); Buckle St Girls’ School, where Bertha went (pink), and Taranaki St Boys’ School, where Will went (blue); Sydney Street Cemetery (white). Ref: NLNZ ALMA 9918213671202836. National Library of New Zealand.

Detail of a map of Wellington showing where William James and Charlotte lived in Taranaki St, ca 1878-1887 (red); Constable Street, 1888 (dark red); Belfast St and Sussex Square, ca 1890-1895 (yellow); Gordon St, 1892 (orange); William St, ca 1896-1933 (purple). Thompson St, where Bertha and Bertram Bird lived before they married in 1888 (green). Also Wellington Gas Company, where William James worked ca 1878-1883 (light brown) and Ballinger’s, where he worked 1883-1912 (dark brown); Church of Christ Dixon St (black), Wellington South (lime) and Kilbirnie (dark blue); Buckle St Girls’ School, where Bertha went (pink), and Taranaki St Boys’ School, where Will went (blue); Sydney Street Cemetery (white). Ref: NLNZ ALMA 9918213671202836. National Library of New Zealand.

Charlotte’s later years

William James died in 1919, aged 72, and Charlotte continued to live at 33 William St, with their youngest son. Bert married in his late forties and had a daughter, Pam, in 1938, the same year as Bertha’s granddaughter, my mother, Margaret, was born.

Although they were the same age, the cousins did not know each other until they made contact on an Ancestry message board in 2001, perhaps because of a rift in the family over Charlotte’s will.

In her will, which can be viewed in the Archives New Zealand Probate Records on Family Search, Charlotte left money to her adopted daughter, May, and her sister Ellen’s daughter, Mary Godkin, who came to New Zealand in 1920. The residue of her estate, including her house, she left to her youngest son, Bertram Jesse, with the request that he remember May’s family in his will. Charlotte’s will did not mention the children of her deceased children, Bertha and Will, though we know that Bertha’s children spent time with her.

Photograph of Charlotte and May’s children Jack, Ken and Madge, late 1924. The children, who lived in Nelson, had regular holidays with their grandmother. Taken from a small original print given to the author’s mother by her cousin Madge Wilson, ca. 2000. The people in the photograph were identified by Madge in a letter dated 6 August 2001. Digitally restored by Camera House, Lower Hutt, in 2023. Used by permission.

The memories of grandchildren

May’s daughter Madge wrote in a letter that her ‘Gran was rather a forbidding lady’. Charlotte’s granddaughter Velma, too, told my mother that she was a little scared of Charlotte and her efforts to teach her the French language. Pam, only a baby when Charlotte died, was told that, after she was born, Charlotte gave her piano away because she had wanted a grandson. From these memories, we have a glimpse of her in later life, through the eyes of young children.

We also learn, from Velma’s recollection, that Charlotte, whose parents were illiterate, must have benefitted from a good education, learning not only to read and write English but also to speak French well enough for her granddaughter to think she was French. Education was important to the Primitive Methodist Church and the Church of Christ, both as a means by which to raise families out of poverty and to allow them to study the bible and this may have been influential.

Photograph, taken ca 1917, showing from left: Bertha Bird nee Durrant, Bertha’s daughter Lottie Jenness nee Bird, Lottie’s son Len Jenness, and Charlotte Durrant nee White. Auckland Libraries Heritage Images Collection.

Charlotte’s death

Charlotte died on 25 May 1939 in Wellington Hospital. Her death certificate states that she had suffered from auricular fibrillation and myocardial degeneration for a period of years, and cardiorenal failure and uraemia for a short time before her death. It was also noted that she suffered from dementia.

Finding the Durrant family grave

Charlotte died just over a year after her great-granddaughter Margaret (my mother) was born in Lower Hutt. Mum only discovered where her great-grandmother was buried in the 1990s when she started researching our family history. It was a time when the value of researching both women’s history and family history was beginning to be appreciated by many.

Through the New Zealand Society of Genealogists, my mother discovered such taonga as school records at Archives New Zealand, which she helped to transcribe, and the Turnbull’s Shotter Collection of images of graves in the Bolton Street and Sydney Street cemeteries, taken by the City Sexton before they were disinterred to make way for the motorway.

Margaret Alington’s Bolton Street Cemetery transcripts, notes and papers, also held by the Library, contain transcriptions of the headstones, death notices and death certificates that are useful for family historians.

Photograph of the grave of Thomas Clatworthy and the Durrant family plots 22.E and 23.E, Sydney Street Cemetery. Ref: 35mm-25589-16A-F. Alexander Turnbull Library.

From these records, Mum found that Charlotte was buried at Sydney Street Cemetery, Thorndon, with her husband and their little sons Albert and Alfred, and Will who, having been gassed in World War I, died in 1923. Less than 40 years after Charlotte was buried, she and her family’s remains were disinterred and placed in a mass grave at the Bolton Street Memorial Park.

The Durrant family plaques are some of the few that can still be seen in the Bolton Street Memorial Park. Taken from the grave, they now lie prone in the grass, passed regularly by strangers rushing through their day, and visited occasionally by descendants discovering, or reconnecting, with their past.

The changes in a lifetime

My Durrant ancestors were proudly working class, idealistic and strong. They were drawn by the Industrial Revolution from Norfolk and Suffolk to seek work in ugly Canning Town and were brave enough to leave the life they had known, in the hope of a better one in New Zealand.

Charlotte White, and the Durrant family she married into, were active members of churches and a friendly society that cared deeply about the moral, spiritual and physical welfare of people. Like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which aimed for a ‘moral uplifting of humanity’, they hoped that if women gained the vote, they would support social and humanitarian reforms, to the benefit of women, children and working-class families.

Through her association with non-conformist churches that encouraged literacy, bible study, public speaking and leadership, Charlotte benefited from an education her ancestors did not have. While gaining the vote was momentous for New Zealand women, I have no doubt that education, and becoming literate, was the most liberating force for Charlotte.

Tracing your maternal line blog series

This is a three-part series. In Part one, we traced my direct maternal line in Suffolk and Essex, England, in the 18th and 19th centuries using family history resources like parish records, civil registrations of births, deaths and marriages, census records and maps.

In Part two, using a variety of family history and genealogy resources Research Librarian, we trace my ancestors’ journey from England to New Zealand aboard the Waimea in search of greater opportunities and a better life.

In the third and final part of this series, we will use civil registration, directories, the 1893 suffrage petition, electoral rolls and recollections from family members to follow Bertha Durrant’s story from Wellington to Lower Hutt.

Tracing your maternal line: Part I — England in the 18th-19th centuries

Tracing your maternal line: Part II — The Durrant family in New Zeal

Selected sources

General

New Zealand Electoral Rolls on Ancestry Library Edition and microfiche

Newspapers on Papers Past

Wises’ New Zealand Post Office Directory on Ancestry Library Edition and

Wellington

A Strange Beautiful Excitement: Katherine Mansfield’s Wellington 1888-1903 by Redma Yska. Otago University Press: Dunedin, 2017.

Wellington: Biography of a City by Redma Yska. Auckland, N.Z.: Reed, 2006.

Manchester Block

Emigrant and Colonists Aid Corp Ltd Records, MDC 00001:3:23. Feilding Borough Council on Archives Central.

School records

Mount Cook School Records, MS-Group-0121. Alexander Turnbull Library.

NZSG Kiwi index [electronic resource], New Zealand Society of Genealogists

New Zealand Society of Genealogists: Transcriptions of the Mount Cook School admission records, MSDL-0247. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Church of Christ

Associated Churches of Christ in N.Z., Wellington City Church: One Hundred Years a Precis of the Past, 1869-1969.

Centennial Souvenir: Being a Brief History of the Associated Churches of Christ in New Zealand, 1844-1944. Wellington, N.Z.: G. Deslandes Ltd., 1944.

From Cottages to Congregations: A History of Churches of Christ in New Zealand from 1844 to 2004 by Mark Willis. Tauranga, N.Z.: M. Willis, 2009.

Jubilee Pictorial History of Churches of Christ in Australasia edited by A.B. Maston. Melbourne: Austral Pub. Co., 1903.

The New Zealand Christian. Auckland N.Z.: Churches of Christ, 1918-

Vickery, Milton (Rev): Church of Christ records, MS-Group-1349. Alexander Turnbull Library

Wellington [N.Z.]: Associated Churches of Christ in N.Z., Wellington City Church, [1969]

John Knox Lodge

Protestant Alliance Friendly Society of Australasia: Records, MS-Group-1133. Alexander Turnbull Library.

Sydney St and Bolton St Cemeteries

Alington, Margaret Hilda, 1920-2012: Bolton Street Cemetery transcripts, notes and papers, compiled by Margaret Alington and others, MS-Papers-2260, Alexander Turnbull Library.

Shotter, P J E: Negatives and albums (with index) of graves in the Bolton Street and Sydney Street cemeteries, Wellington, PAColl-3096, Alexander Turnbull Library.

Unquiet Earth: A History of the Bolton Street Cemetery by Margaret Alington. Wellington, NZ: Wellington City Council, 1978.

Suffrage

A History of New Zealand Women by Barbara Brookes. Wellington, New Zealand: Bridget Williams Books, [2016].

Leading the Way: How New Zealand Women Won the Vote by Megan Hutching. Auckland: Harper Collins, 2010.

The Ladies are at it Again!: Gore Debates the Women’s Franchise by Rosemarie Smith. Wellington, N.Z.: Women's Studies, Victoria University of Wellington, 1993.

The Women's Suffrage Petition = Te Petihana Whakamana Pōti Wahine, 1893. Wellington, New Zealand: Archives New Zealand, Te Rua Mahara o Te Kāwanatanga: National Library of New Zealand, Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa: Bridget Williams Books, 2017.

Women’s Suffrage in New Zealand by Patricia Grimshaw. Auckland University Press: Auckland, 1987.

Immigration

Archives New Zealand, Passenger Lists, 1839-1973 on FamilySearch

Outwards Passenger Lists 1852-1923 on Public Record Office Victoria website