How teachers who read create readers

Sue McDowall, a senior researcher at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER), discusses her study exploring how teachers who are readers support reading for pleasure in their schools and classrooms.

An interview with Sue McDowall on teachers as readers

In this interview, Jo Buchan talks with Sue about an exploratory study Sue did in 2021 for the National Library of New Zealand | Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa. The purpose was to investigate possible associations between the personal reading practices of teachers who read for pleasure and their engagement with students around text. As part of the research, Sue interviewed 9 primary and intermediate school teachers, including 3 school leaders who identified as passionate readers.

The research is part of a wider suite of 6 studies commissioned by the National Library as part of the Communities of Readers initiative.

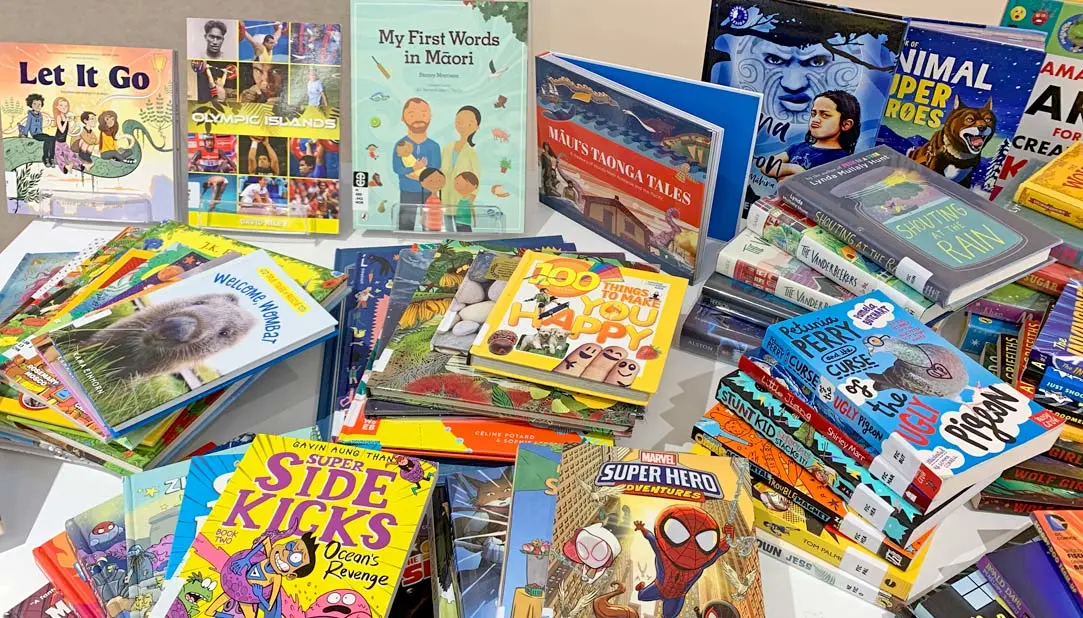

Book display at a National Library reading event for educators.

How teachers who are readers share their reading selves in class

Jo Buchan: This research focused on how teachers who are readers engage with students around books in their classrooms. How did you land on this focus?

Sue McDowall: For about 10 years, Elizabeth Jones (Director Literacy and Learning at the National Library) and I have had conversations about reading for pleasure and our concern that it seemed to be disappearing out of primary school classrooms.

Jo Buchan: This is quite a small-targeted research piece. Why this approach?

Sue McDowall: One reason was because I wanted in-depth information. There have been big surveys done overseas on teachers as readers. Because survey questions are quite broad, they tend to give good quantitative data, but not much detail about what teachers are doing in their classrooms and why. My interest is shifting practice, and I think that's done well when we find out what the teachers who are really good at supporting reading for pleasure do, and share those ideas.

Also, the research project was small because it was exploratory. It would be great to do a more extensive qualitative research project on this topic in the future.

Teachers’ identities as readers

Jo Buchan: The teachers in this study all identify as avid readers. Why was it so important to have readers for this research?

Sue McDowall: There's a lot of work already about how the identity of a teacher matters, so it's not just what you teach, but it's who you are. I was interested in exploring the idea of teachers who are themselves readers, how they felt that came with them into the classroom. We did a research project about 10 years ago, called Lifelong Literacy. An incidental finding from that project was that all teachers in the study were very keen readers. We would chat before the research meeting started about what they've been reading, just like readers do. But when they started talking about the teaching of reading in class, it was completely different. They weren't doing the things they did as out-of-school readers. That got us curious about why.

Jo Buchan: Yes, that’s fascinating. Did you have a hypothesis about why that is?

Sue McDowall: There is a book by Dennis Sumara called Why Reading Literature in Schools Still Matters: Imagination, Interpretation, Insight. In it, he argues that in school contexts we treat texts as if they're closed, as if there's just one right answer to find. But in out-of-school contexts, we treat texts as if they’re open to interpretation and discussion. Reading can sort of ‘get schoolified’. It’s an interesting question. When I was at primary school, and also when I was a teacher, I think there was a lot more focus on reading for pleasure and reading to children. And the pendulum swings back and forwards. We’ve had a period where I think the focus has been more on processing skills and comprehension strategies. One of the teachers said he knew colleagues who felt they weren't allowed to have time on reading for pleasure in class because the focus was so much on lifting achievement.

Jo Buchan: What was a significant finding for you from this study concerning that question?

Sue McDowall: That teachers saw their identity as readers as one of the most important factors in supporting their children to become readers. They did all those things we know are good to do. They read to the children. They provided children time to read silently for pleasure on their own, and to talk with each other about the texts. But what they thought made the most difference was that they themselves were readers in and out of school time. They brought their identity into the classroom and talked about books, thought about books and interacted with books in ways that were different because they were readers.

Jo Buchan: Did bringing their reading identity into the classroom have an impact on their students?

Sue McDowall: Certainly, the teachers in our study felt it did make a difference to their students. They made the point that you can't fake being a reader. You can sit there with your book reading during silent reading time. You can encourage reading and all those things are important and good but, students know if you're really a reader.

Jo Buchan: What does that mean for teachers who don’t consider themselves a reader but know it's important? What steps can they take?

Sue McDowall: In my experience, most people do read. It's just that we have such a narrow idea of what counts as reading that people think they’re not a reader because they're not reading Jane Austen or don’t fit with our traditional idea of what a reader does. I’d suggest thinking about what they are reading, whether they're reading when they're playing video games or reading Wikipedia posts entries. The secret is to find the topic they're passionate about or the sort of reading they might do and bring it into the classroom.

Similarities in practice and early reading experiences

Jo Buchan: The study highlighted participants' similarities in terms of practice. For example, they were all reading to their students. It also mentions similarities in their early reading experiences. Can you tell us more about this?

Sue McDowall: I was interested in looking across the teachers’ whole life spans to get a sense of the context they were bringing to their teaching. We know that readers are made and the teachers in the study all came from very different backgrounds. They were different ages and had different teaching and life experiences. I was curious to know about those differences and how they linked to their early selves as readers and forward into their classroom teaching. What they shared was that they nearly all saw themselves as readers as children. They started reading very early, identifying as readers through listening to stories being told or listening to stories being read.

Often, there was a strong role model in their family who modelled not just reading for pleasure, but all the practices associated with reading for pleasure like talking with friends about books and sharing books with friends. There was often an identity component to their early experiences that might link to that family member who was a reader, often to their cultural background. Those reading role models were quite important in those formative years.

Jo Buchan: You reference Teresa Cremin’s research in the UK around teachers as readers, which highlights the importance of being a reader. It also found that some teachers had a limited knowledge of books, often defaulting to those they’d read when young. Was that something that you found?

Sue McDowall: I've seen that a lot. Even when teaching, I also either defaulted to books I read as a child and there is a place for these books, but they can be quite dated. Being aware of all the fabulous contemporary fiction and non-fiction is important and to provide students access to that.

Jo Buchan: Did the context of where the study participants were teaching impact their classroom practice?

Sue McDowall: We tried to get a range and they came from decile 1 to decile 9 schools and from urban, rural, small and large schools. We tried also to get a range of teaching experience but tended to have mid-career or experienced teachers. Overall, the context was varied.

It was also important to the teachers of being aware of who comes to your school and of the families in your community. People come to school with different first languages and different ways of speaking English and different values. Also, to think about the student’s home languages and literacies, and to make sure they offered them mirrors in which they could see themselves and windows to other places.

There was at least one teacher in a school with a high Māori and, especially, Pacific enrolment. The challenge for her was finding books written in the children's first languages or even books where they could see themselves represented at all. In the end, she got them to create their own books, which could go into the school library so they would have material where they saw themselves. I think that is a challenge, although I know there are lots of fantastic new books coming out by Māori and Pacific writers.

Practices shared

Jo Buchan: You touched on some of the practices the teacher shared. Can you expand on some of those?

Sue McDowall: They talked incidentally about their own reading in the presence of children, so they might be in the school library choosing books and chatting with the librarian about a book they’d both read. Likewise, if a teacher has their own book they're reading in their bag or are sitting at lunch reading a book, children notice those things.

These teachers felt they showed a level of pleasure and passion about the books they read to children. When talking with children about the books the children were reading themselves, they were genuinely interested in the books and how children make meaning of them. Especially books with ambiguity where they could say things like, ‘What did you think about the way it ended?’ They saw those conversations with children as a way of connecting with and getting to know them.

They also talked about texts in different ways from how you might talk about a text in a guided reading lesson. In everyday life when readers are talking to each other, say in a book group or with a friend, they are saying things like, ‘I remember a time when I felt like that character, and this is what happened’ or 'What did you make of the way that story ended?’ It was about interest and pleasure and connecting with children and texts. It wasn't about seeing whether that child had read the book, whether they understood the book and how many books they were reading. It wasn't performative. It was about relationship and meaning-making, individually and collectively.

Some of the teachers also just allow children time to read and chat. When I was a teacher, it always had to be very silent. You had to start reading and then silent reading would end. Whereas in these classrooms, teachers have kids sitting on beanbags in the library reading books, chatting, sharing books and pointing out things in each other's books. This social aspect of reading was important.

Teachers’ aspirations for their students as readers

Jo Buchan: When asked, ‘What do you want for your students as readers?’ none of the respondents answered with responses such as to develop processing skills or strengthen comprehension strategies. What is the significance of this for school leaders?

Sue McDowall: I guess that was quite a provocative statement, but what all these teachers did is keep their eye on the purpose for reading. At no time in our life do we read purely to improve our processing skills and comprehension strategies except when we’re at school. Of course, these teachers taught processing skills and comprehension strategies and saw these were important and interesting and fun. But they were in the service of the big purposes for reading: reading for pleasure, reading for interest, for information, curiosity, for escapism, for wellbeing, all those reasons that people read.

Jo Buchan: Is reading for pleasure still important in the early primary years? There’s some debate about that.

Sue McDowall: Yes, it’s remembering that reading for pleasure counts as learning. There's so much research that shows children who read for pleasure have all sorts of better life outcomes including achievement. And that reading for pleasure includes reading to children. We can read things to children they can't read themselves. We can stretch children in what we read to them.

Jo Buchan: Are you talking about reading to them just for enjoyment, without any work attached?

Sue McDowall: Yes, and for the teachers’ pleasure as well. Reading is meant to be a joyful, purposeful, exciting experience and learning skills is important so you can have those experiences, it’s not an end in itself. Children who don't have opportunities to engage with texts for pleasure and have access to text beyond what they can read themselves are disadvantaged further down the track. It's through those experiences of reading and talking about texts that you build your capacity to make meaning and you build a vocabulary and you do it in a way that's meaningful and purposeful and fun.

A need for future research

Jo Buchan: You talked earlier about the need for future research. Can you talk more about that?

Sue McDowall: There's a need for research that involves listening to what students have to say about their experiences of reading in schools, the good and the not-so-good experiences. And, what students (who have teachers who are passionate readers) learn and pick up from those teachers, what they remember about them. There was a lovely story from one of the teachers I spoke with, who met a child she had taught 30 years earlier who approached her and said, ‘the thing I remember about you is the stories you read us’. What a legacy for a teacher.

I’d also be interested to hear how many teachers saw reading as linked with their own wellbeing in their out-of-school lives and how they saw that as something they could offer to their children. Especially children who came from difficult home backgrounds or stressful situations at home. To offer them that escapism and relaxation that comes with reading for pleasure is a real gift.

For me, it’s bringing back into the classroom the joy of reading as well as teaching children how to read. It’s enabling children to see themselves as readers.

If you look at, for example, National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement (NMSSA) data, it shows that over the last 10–20 years, enjoyment of reading has been dropping. Students seeing themselves as readers is steadily dropping as well over time. There are all sorts of reasons why that might be. We should be worried about this because we know that readers have better outcomes.

Jo Buchan: There’s also a decline in deep flow, long-form reading.

Sue McDowall: In teaching, we tend to give small amounts of text to children and there is good reason for that, but it’s also important for children to be able to read through a longer text.

This reminds me of another thing about teachers in this study. They shared high expectations and didn’t dumb down the material they read to children; they kept the level high and challenging. They also had high expectations of the sort of talk children would engage in around text. They would push for an extended response from a child that asked why they thought what they thought. What happened in the text that made them think that?

Our job is not just to teach children how to read but it's to enable children to be readers. And I would say that is something that should not be left to chance. It is a right of all children, to have the opportunity to develop the pleasure that comes from reading.

Jo Buchan: Thank you Sue and we look forward to hearing about your future research in this space.

About Sue McDowall

Sue McDowall is a Senior Researcher at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER). She has a primary school teaching background and taught for 8 years, mainly for years 4, 5 and 6. She studied English literature and has a passion for books and reading.